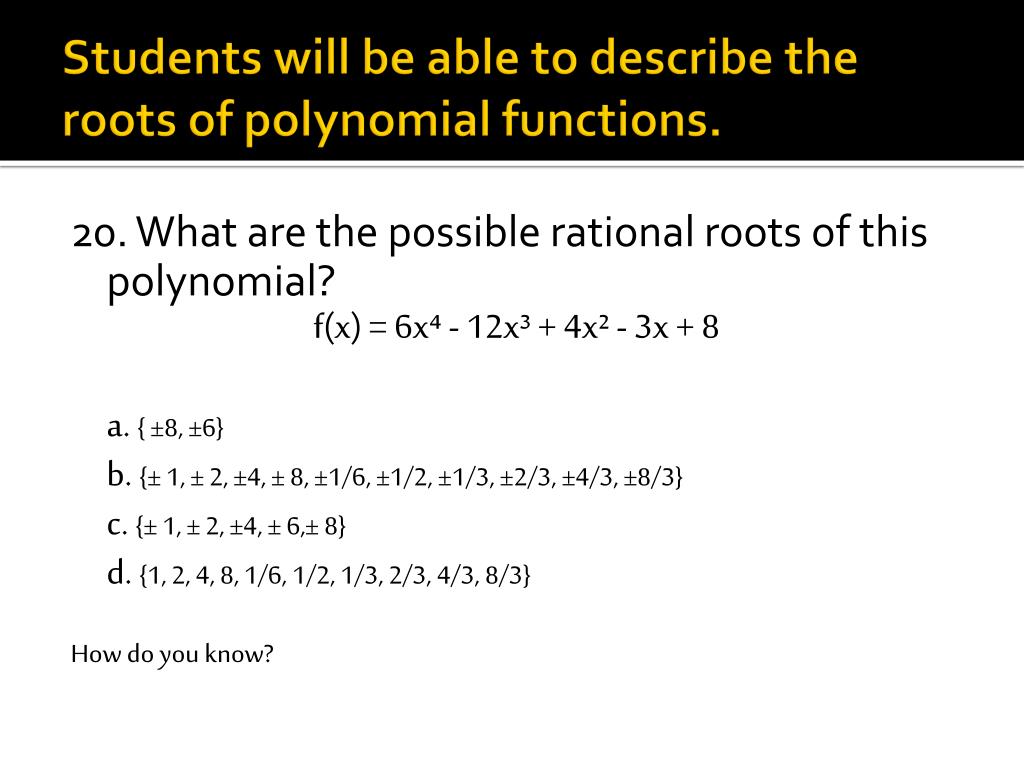

What Is the Root of a Function? Unlocking the Core of Polynomial Mathematics

What Is the Root of a Function? Unlocking the Core of Polynomial Mathematics

The root of a function lies at the heart of algebraic understanding, serving as the critical solution point where a function’s output equals zero. More than just a zero value, the root—also known as a zero or residual—represents the input that collapses the function to its lowest point, revealing essential behavior about its shape, domain, and applicability. Whether in basic linear equations or complex higher-degree polynomials, finding roots allows scientists, engineers, and mathematicians to decode relationships, predict behavior, and solve real-world challenges rooted in mathematical modeling.

The Definition: Where a Function Meets Zero

Mathematically, the root of a function is the value of the independent variable, typically denoted \( x \), for which the function’s output equals zero.

Given a function \( f(x) \), a root satisfies the equation \( f(x) = 0 \). For instance, in the quadratic function \( f(x) = x^2 - 5x + 6 \), solving \( x^2 - 5x + 6 = 0 \) yields roots at \( x = 2 \) and \( x = 3 \)—values where the parabola crosses the x-axis. Roots may be real or complex, rational or irrational, depending on the function’s form.

Unlike the y-intercept, which indicates function value at \( x = 0 \), the root reflects structural equilibrium, a pivotal concept in algebra and calculus.

The Algebraic Significance of Roots

Roots reveal the solutions to polynomial equations—cornerstones of mathematical analysis. Each root corresponds to an intersection point with the horizontal axis, directly influencing a graph’s visual layout and inferred behavior. Consider \( f(x) = (x - 1)(x + 2) \); setting \( f(x) = 0 \) uncovers roots at \( x = 1 \) and \( x = -2 \), offering immediate insight into how the function changes sign and transitions through the axis.

In advanced applications, roots determine stability in control systems, resonance frequencies in acoustics, and equilibrium points in physics models.

Types of Roots: Real, Complex, and Multiplicity

Roots are categorized by their mathematical nature and multiplicity. A real root corresponds to a point where the graph touches or crosses the x-axis; complex roots, involving imaginary numbers, emerge when no real solutions exist. For example, \( f(x) = x^2 + 1 \) has no real roots but possesses complex ones at \( x = i \) and \( x = -i \), critical in signal processing and electrical engineering.

Multiplicity further defines root behavior: a simple root (multiplicity one) means the graph crosses the axis, whereas a double root (multiplicity two) causes the curve to flatten and bounce off, as seen in \( f(x) = (x - 4)^2 \). Multiplicity shapes the contour of polynomial graphs, influencing aesthetics and analytic interpretation.

Methods to Find Roots: From Factoring to Numerics

Several approaches unlock roots, each suited to different function types and complexities. Direct algebraic methods—such as factoring, completing the square, or using the quadratic formula—work elegantly for low- to moderate-degree polynomials.

The quadratic formula, \( x = \frac{-b \pm \sqrt{b^2 - 4ac}}{2a} \), outlaws uncertainty in quadratics and extends to cubic and higher-degree equations via analytical formulas, though limitations exist for degree five and above. For more intricate functions, numerical techniques refine approximation: the Newton-Raphson method iteratively converges toward roots, powerful but sensitive to starting values, while the bisection method guarantees convergence within bounded intervals through interval halving—ideal for stable, real-valued solutions.

Real-World Applications of Root Analysis

Root finding transcends pure math, fueling innovation across disciplines. In engineering, roots determine natural frequencies in structural dynamics, ensuring buildings withstand vibrations.

In chemistry, equilibrium concentrations often satisfy polynomial roots derived from reaction kinetics. Electrical circuits rely on root analysis for stability and resonance, with polynomial equations describing signal responses. Financial modeling uses roots to forecast break-even points, where revenue equals cost.

Each application hinges on accurately determining \( x \) where function output vanishes, transforming abstract solutions into actionable insights.

Visual Insight: Roots as Graph Intersections

Graphical representation transforms abstract roots into tangible understanding. The x-axis intersections of a function’s curve with \( y = 0 \) become immediate visual anchors—each crossing point a root. For \( f(x) = x^3 - 4x \), plotting reveals roots at \( x = 0 \), \( x \approx 1.15 \), and \( x \approx -1.15 \), illuminating the cubic’s three real roots and symmetric behavior.

Such visualizations reinforce conceptual clarity, showing roots not as isolated numbers, but as dynamic focal points shaping function topology and enabling intuitive analysis.

Roots Are the Language of Function Behavior—Why Understanding Them Matters

The root of a function is far more than a variable set to zero—it is the key to decoding a function’s structural essence, from simplest linear graphs to elaborate polynomial systems. It marks equilibrium, signals transformation, and bridges theory with tangible application. Whether uncovering hidden stability in a bridge’s design, optimizing chemical yields, or developing algorithms, recognizing and computing roots empowers precision and innovation.

In the crossroads of algebra and real-world challenge, the root remains not just a value, but a foundational truth about how functions shape understanding laws of mathematics.

Related Post

Peter Fonda Net Worth: A Comprehensive Look At His Life And Wealth

Revolutionizing Digital Asset Tracking with the Invisible Item Frame Command

Tap Sports Bar Menu: A Dynamic Culinary Experience That Elevates Every Event

Shane Gillis’s Sister: The Quiet Force Behind a Controversial Star’s Privacy