What Is An Abdominal

What Is An Abdominal? Understanding the Core of Core Human Anatomy

The abdomen—often mistaken merely as the “stomach region”—is far more than a simple anatomical zone; it is a complex, dynamic structure housing vital organs responsible for digestion, circulation, and immune support. Situated between the thorax and pelvis, this central body compartment shelters the gastrointestinal tract, liver, spleen, pancreas, kidneys, and parts of the urinary system, forming a crucial nexus of metabolic and physiological activity.As medical expert Dr. Elena Torres notes, “The abdomen is not just a hiding place for internal organs—it’s the functional heartbeat of homeostasis.”

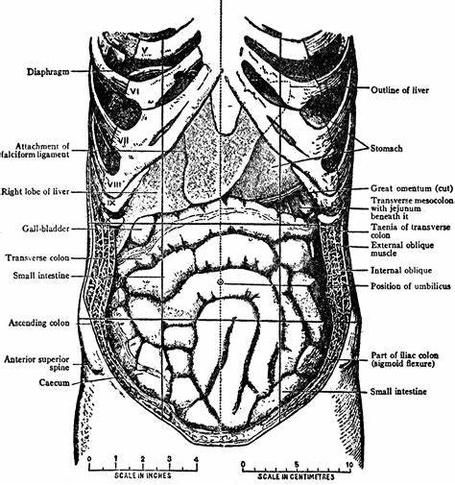

Anatomically, the abdomen is conventionally divided into four quadrants: the right upper, left upper, right lower, and left lower quadrants, a system established in the 19th century to aid precise clinical diagnosis and surgical planning. Six major abdominal walls divide this region: the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles, layered beneath the skin and fat, form a natural corset that stabilizes internal pressure.

This musculature works in concert with deep fascial layers to protect fragile organs and facilitate respiration and gastrointestinal motility. As revealed by advanced imaging studies, the abdominal cavity’s biomechanics support both passive and active movement of organs during digestion, breathing, and physical exertion.

The Abdominal Cavity: Home to Life-Sustaining Organs

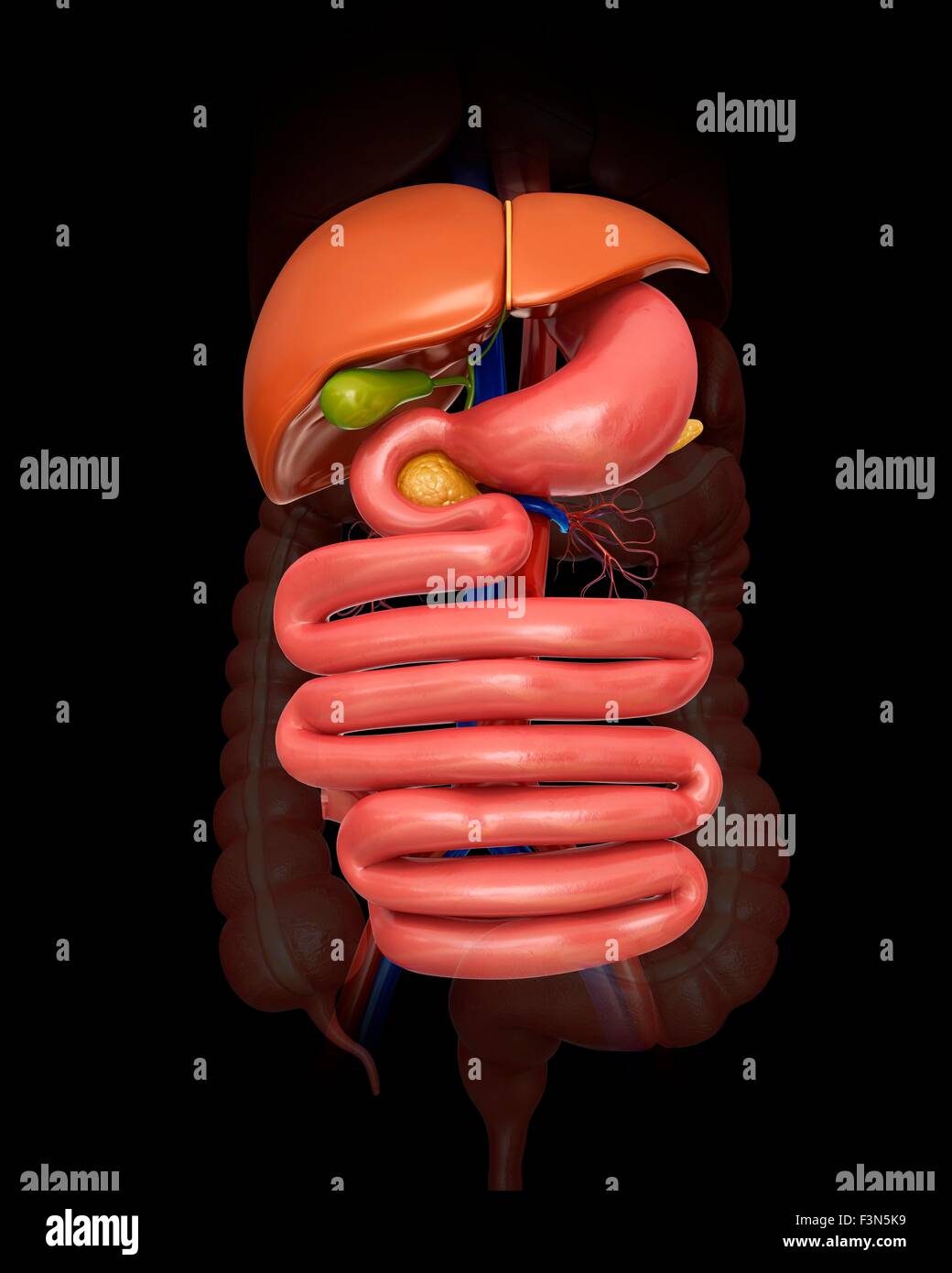

The abdominal cavity functions as a sealed, pressure-regulated environment where organs operate in delicate interdependence. The liver, the body’s largest internal organ, occupies the upper right quadrant and performs over 500 vital functions, including detoxification, protein synthesis, and bile production essential for fat absorption.The gallbladder, nestled beneath the liver, stores bile—a digestive enhancer released into the small intestine during meals. The pancreas, bridging the digestive and endocrine systems, resides along the posterior abdominal wall, secreting insulin and digestive enzymes that regulate blood sugar and break down nutrients. The spleen, located in the upper left quadrant, filters blood, supports immune surveillance, and manages red blood cell turnover.

Meanwhile, the kidneys sit retroperitoneally on either side, filtering waste from blood to form urine, while the intestines extend through the central and lower abdomen, driving nutrient absorption and microbial symbiosis.

Each organ contributes to a tightly coordinated network of physiological processes. The peritoneum, a thin serous membrane lining the abdominal wall and covering internal organs, reduces friction and facilitates smooth organ motion. This fluid-filled sac not only cushions but also serves as a pathway for blood vessels, nerves, and lymphatics.

Disruption of this system—whether through herniation, inflammation, or tumor growth—can have cascading effects across multiple organ systems. For instance, appendiceal inflammation often disrupts gut motility and immune signaling, underscoring the region’s integrated nature.

Functions Beyond Digestion: Metabolic and Protective Roles

Beyond its digestive role, the abdomen plays a pivotal part in metabolic regulation. The liver, as an epicenter of metabolic activity, stores glycogen, converts ammonia to urea, and synthesizes cholesterol and clotting factors.The gastrointestinal tract, extending from the esophagus through the colon, actively absorbs nutrients and houses trillions of commensal microbes that modulate immunity, produce short-chain fatty acids, and influence mental health via the gut-brain axis. The abdominal musculature, particularly the transversus abdominis, supports core stability, spinal protection, and efficient respiration—acting as a natural intra-abdominal pressure regulator during coughing or lifting. Clinical studies emphasize that abdominal strength correlates with reduced injury risk and better postural balance, particularly in aging populations.

Clinical Significance: What Clinicians Watch Closely

Visual inspection of the abdomen remains a cornerstone of physical examination.Healthcare providers assess for asymmetry, distension, rebound tenderness, or guarding—features that signal inflammation, obstruction, or visceral pain. Palpation evaluates organ size, tenderness, and harmonic movement during respiration, helping distinguish conditions like cholecystitis, diverticulitis, or hepatomegaly. Pallor around the umbilicus may hint at chronic dehydration or internal hemorrhage, while visible peristalsis suggests normal motility.

Ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) scans offer non-invasive visualization of soft tissues, revealing masses, fluid collections, or vascular abnormalities with high precision. As Dr. Rajiv Mehta, a gastroenterologist, explains, “Each prominence or shadow in the abdomen tells a potential chapter in a patient’s medical story—timely and precise assessment can be life-saving.”

Abdominal Pain: A Symptom with Many Faces

Abdominal pain is among the most common chief complaints in emergency medicine and primary care, yet its underlying mechanisms remain complex and often elusive.Pain may originate from the viscera—visceral pain—which is typically diffuse, poorly localized, and harder to pinpoint than somatic pain. In contrast, pain from superficial tissues, muscles, or skin is sharper and more localized. Common causes range from benign conditions—such as gastritis or indigestion—to serious events like myocardial infarction, where referred pain may manifest in the epigastrium or left arm.

“Abdominal pain is the body’s alarm system,” says emergency physician Dr. Linh Nguyen, “and decoding its source—whether mechanical, inflammatory, or ischemic—is what separates urgent care from routine treatment.” The localization of pain is guided by anatomical knowledge: upper quadrant pain often signals digestive disturbances, while lower quadrant pain implicates intestinal processes, such as appendicitis or irritable bowel syndrome. Imaging and lab tests remain indispensable for accurate diagnosis, especially when red flags—such as fever, jaundice, or bloody stool—point to systemic illness.

Maintaining Abdominal Health: Lifestyle and Preventive Insights

Preserving abdominal integrity and function hinges on informed lifestyle choices.A fiber-rich diet supports regular bowel movements, reducing constipation and lowering the risk of colon cancer. Hydration maintains tissue elasticity and aids digestion. Regular physical activity strengthens the core musculature, promoting gut motility and metabolic health.

Avoiding excessive alcohol and smoking protects hepatocytes and reduces inflammation. Conversely, chronic stress undermines gut permeability and immune defense, contributing to conditions like functional dyspepsia or inflammatory bowel disease. Regular screening—such as colonoscopies for individuals over 45—detects precancerous polyps and early malignancies, significantly improving outcomes.

Ayurvedic and traditional practices emphasize abdominal massage and breathing techniques to “stimulate veins of life” within, though they remain complementary to medical care rather than substitutes. Collectively, proactive habits fortify the abdomen, turning it into a resilient engine of long-term wellness.

The abdomen, though often overlooked, is a cornerstone of bodily function and health. From orchestrating digestion to regulating metabolism and signaling systemic disease, its complexity demands precise understanding.

Recognizing the abdomen not just as a physical region, but as a living, interconnected system, empowers both patients and clinicians to detect, prevent, and treat conditions before they escalate. As anatomy continues to unfold through technological advances, one truth remains: the abdomen is not just part of the body—it is the body’s command center.

Related Post

Exclusive Sophie Rain as Spider-Man: The Untold Story Behind the Groundbreaking Video You Won’t Find Anywhere Else

500 Pearl St, New York: The Unmarked Pillar of Urban Innovation and Heritage

Unveiling the Mystery Behind the Instagram Girl Viral MMS Sex Phenomenon

Is Otis From Good Burger Really Dead? Decoding a Virtual Legends’ Enigma