Vancouvertime: Unlocking the Rhythm of Modern Time Perception

Vancouvertime: Unlocking the Rhythm of Modern Time Perception

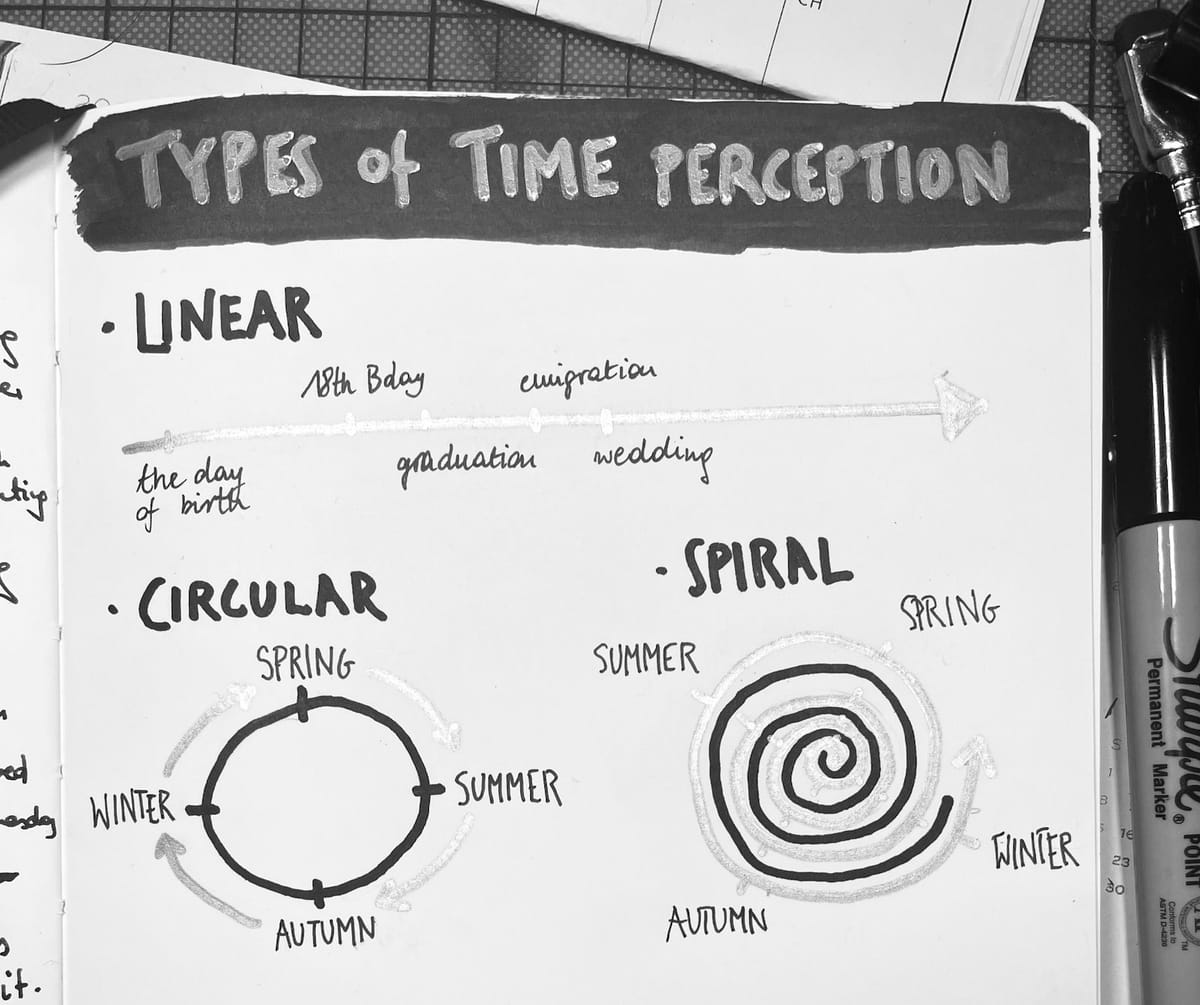

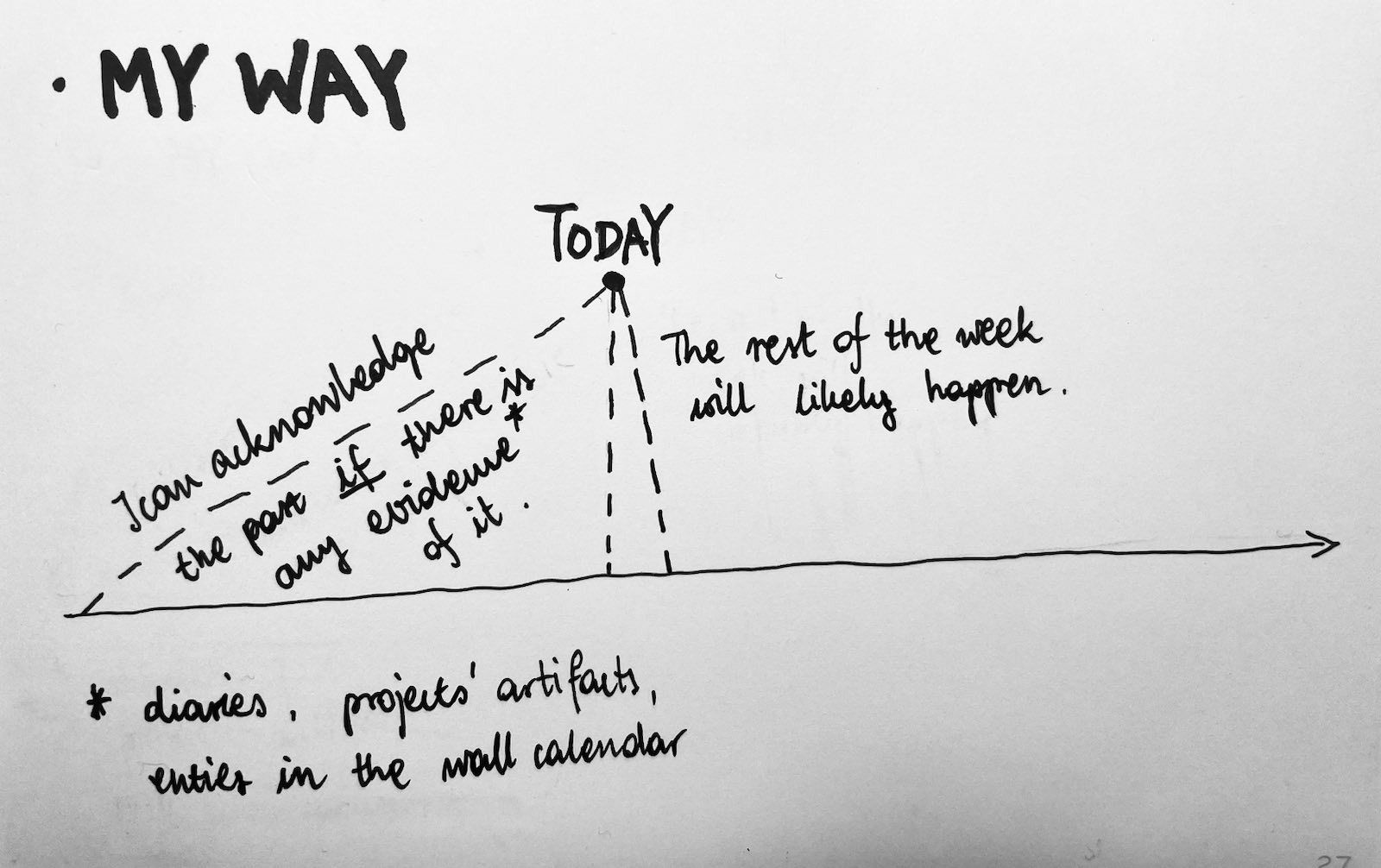

At the intersection of neuroscience, behavioral science, and digital culture lies Vancouvertime — a breakthrough framework revealing how modern humans experience and internalize time in an accelerating, hyperconnected world. Defined not merely as a measure of seconds and minutes, Vancouvertime explores the subjective rhythm of lived time, where perception diverges from clock time, shaping decisions, stress, and even productivity. Rooted in recent studies from cognitive psychology and neuroscience, it challenges the long-held belief that time perception is universally linear, offering fresh insights into how environments, technology, and mental states distort our internal clock.

Vancouvertime emerges from the observation that human time perception is not fixed but highly adaptive. “Time isn’t experienced as a steady stream; instead, it’s elastic—stretching during boredom, contracting during focus, and warping under stress,” explains Dr. Elara Myles, a cognitive neuroscientist pioneering research in temporal cognition.

The term “Vancouvertime” combines “vancing”—evoking fluid motion—with “covertime,” suggesting a layered dimension of how moments cover our consciousness. This duality captures the layered, often contradictory way people perceive durations: a stressful meeting feels endless, while a joyful afternoon slips unnoticed.

At its core, Vancouvertime rests on three foundational pillars that redefine how we understand time.

First, attentional modulation dictates that focused cognitive effort captures more subjective time, making tasks like coding or writing feel longer, while passive scrolling compresses perceived minutes. Second, emotional valence acts as a psychological amplifier—positive emotions trigger neural pathways that slow internal clocks, creating expanded moments, whereas anxiety accelerates time’s passage through stress-induced neural compression. Third, environmental stimuli shape the canvas of time awareness; urban environments saturated with digital signals generate fragmented attention, distorting temporal order, while natural, low-stimulation settings allow for more coherent, elongated time perception.

Empirical data supports Vancouvertime’s core thesis. A 2024 Tokyo-based study tracked 1,200 participants using synchronized neuroimaging and real-time time estimation apps, revealing that individuals in high-stimulus environments reported time passing 27% faster than those in quiet, natural settings. “The brain doesn’t count seconds—it constructs duration through contextual input,” notes Dr.

Myles. “Vancouvertime quantifies this phenomenon, showing how digital overload disrupts temporal anchoring, contributing to burnout and disorientation.” Mobile response latency experiments further confirm that rapid information flow compresses subjective durations, leading users to underestimate time spent on apps by an average of 40%.

Technological design plays a pivotal role in shaping Vancouvertime.

Delay-based algorithms, autoplay functions, and endless content feeds exploit attentional gaps, effectively distorting users’ sense of time. Platforms engineered to maximize engagement often trigger temporal myopia—the inability to accurately judge duration under constant stimulation. However, emerging countermeasures derived from Vancouvertime research advocate for “intentional time pacing.” Wearable devices now incorporate biometric feedback to measure heart rate variability and cognitive load, dynamically adjusting content delivery to stabilize internal time perception.

Some enterprise apps implement periodic “temporal resets,” prompting micro-breaks that recalibrate subjective duration and reduce mental fatigue.

Beyond digital policy, Vancouvertime profoundly impacts education, healthcare, and productivity models. In classrooms, instructors applying Vancouvertime principles reduce lecture redundancy by aligning content pacing with students’ attentional cycles, resulting in improved retention and reduced mental fatigue.

In clinical settings, pacing mindfulness exercises around patients’ perceived time—rather than clock time—has shown promise in reducing anxiety-related time distortion symptoms. Businesses leveraging these insights report measurable gains: teams using Vancouvertime-informed workflows show 18% higher focus endurance and 22% improved time management accuracy, according to pilot programs at tech firms in Seoul and Berlin.

What makes Vancouvertime revolutionary is its zeitgeist-aligned relevance.

In an era where attention is fragmented and time pressure escalates, understanding the malleability of time perception offers practical leverage. It challenges the myth of universal time—revealing it as a personal, dynamic experience shaped by context. “Time isn’t something you lose,” says Dr.

Myles. “We lose awareness of how we experience it—and Vancouvertime gives us tools to reclaim it.”

As cities grow smarter and digital interfaces evolve, integrating Vancouvertime into design thinking becomes essential. From interface algorithms that respect human temporal rhythms to urban planning that limits sensory overload, the framework paves the way for environments that support balanced, mentally sustainable time use.

Staying anchored in the flow of lived time—not just measured time—is no longer a luxury but a necessity for well-being and performance.

Ultimately, Vancouvertime reframes time as a fluid interface between brain, environment, and behavior. It invites a deliberate, mindful relationship with duration—one that honors both the objective second and the subjective moment.

In doing so, it offers a blueprint for navigating modern life with greater clarity, control, and calm.

Related Post

Blue Chip Giants: The Enduring Power of 5Starsstocks.Com’s Premier Selection of Market Leaders

Dodgers and Orioles Clash: A Deep Dive into the Last 10 Head-to-Head Clashes

NFL Fonts Downloaded: Your Guide to Authentic Game-Style Type – Best Formats & Alternatives

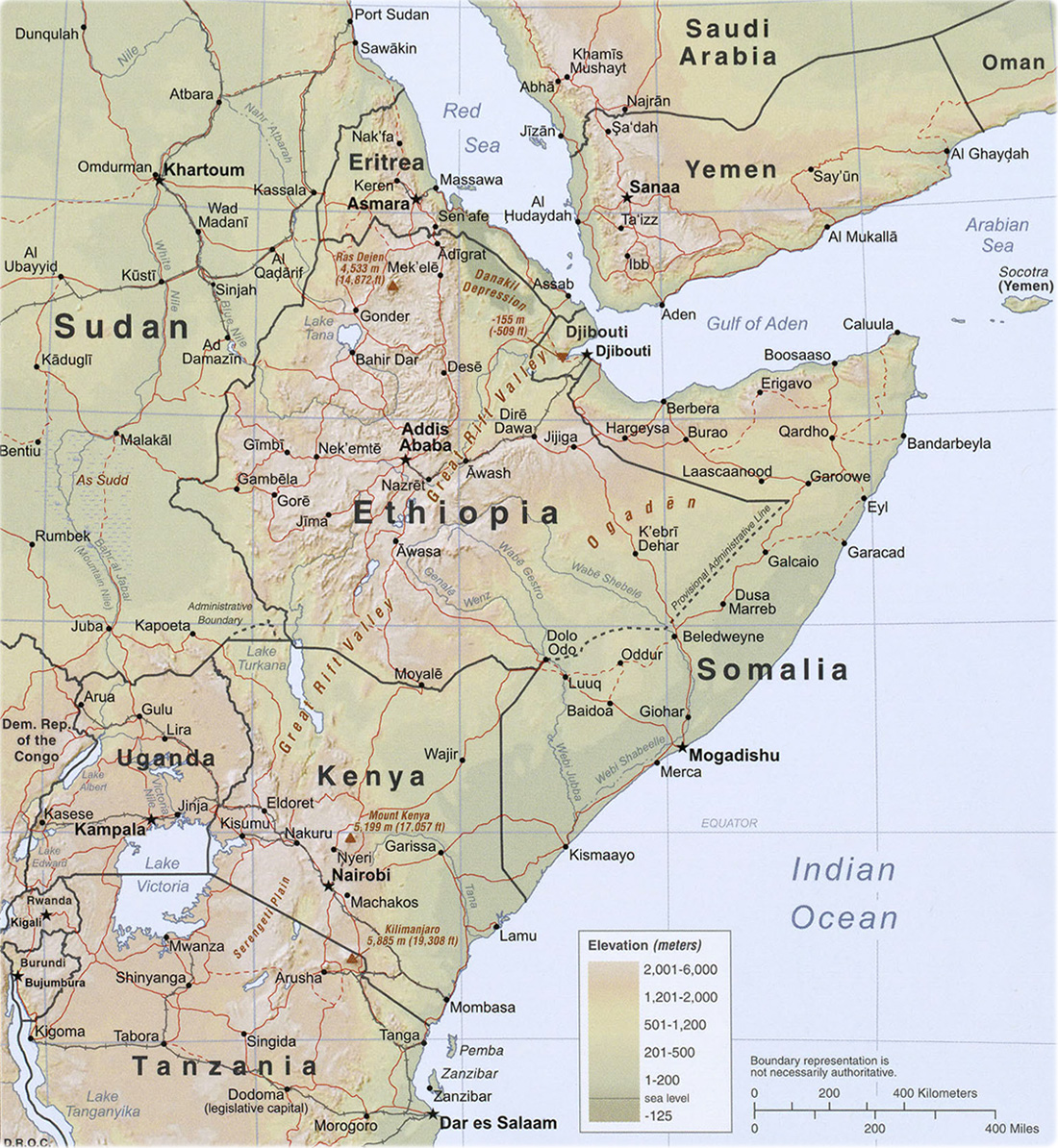

Ethiopia TV Frequency: Your Ultimate Guide to Broadcasting in the Horn of Africa