Us State Capitals An A-Z Guide to America’s Capital Geography

Us State Capitals An A-Z Guide to America’s Capital Geography

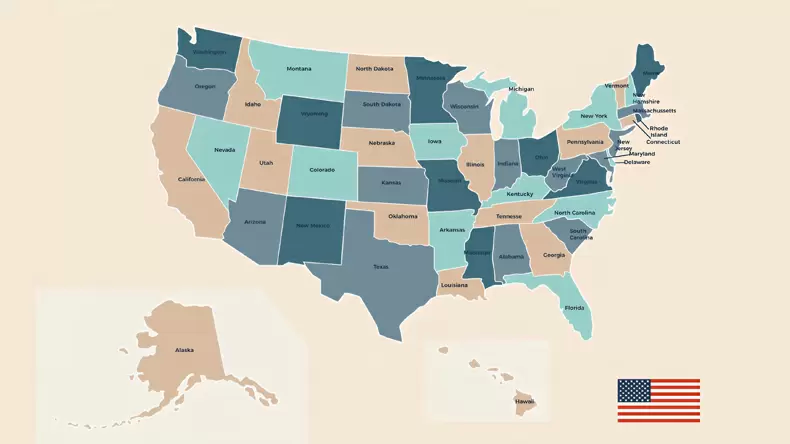

From Portland in the misty northwest to Cape Canaveral in the sun-bathed southeast, the 50 state capitals form an intricate map that reflects history, culture, and geography across the United States. Anchored by a deliberate A-to-Z ordering, this guide navigates the chapter-by-chapter capital sequence, revealing how each seat of state government carries unique stories of founding, development, and identity. Whether you’re a curious traveler, a geography enthusiast, or a student of American federalism, this chronological journey through the capital names uncovers unexpected patterns, regional quirks, and the pivotal roles these cities play in state governance.

Ranging from the northern reaches to the southern tip, the list begins with Augusta — Tennessee’s capital, a city where Civil War echoes mingle with Southern tradition — and progresses through capitals like Sacramento, Boise, and Annapolis, each embodying distinct regional character. Dakota, Jefferson, and Salt Lake each reflect their state’s unique heritage, from Native influences to Mormon roots. Even capitals in the Atlantic coastal belt — Annapolis, Trenton, Tallahassee — share stories of early settlement and strategic planning.

This A-Z sequence isn’t just alphabetical noise; it’s a curated map of America’s political landscape, where geography shapes history and identity.

How the A-to-Z List Organization Shapes National Awareness

The decision to arrange state capitals in alphabetical order serves more than organizational convenience. It transforms a potentially dry fact into an accessible, navigable resource. For educators, students, and travelers alike, a rolling alphabet provides a predictable rhythm, enabling quick reference and pattern recognition.“The A-to-Z structure simplifies learning,” notes Dr. Elena Ramirez, professor of civic geography at Stanford. “It allows users to move through states chronologically, reinforcing spatial memory and making regional connections tangible.” Capitals indexed this way highlight underrepresented regions often overshadowed by state-sized capitals like Washington, D.C.

For example, Bismarck (North Dakota) and Boise (Idaho) emerge not just as seats of power but as cultural and administrative hubs in states whose economies and histories thrive beyond urban centers. This order ensures that capitals from “small” or “remote” states are visible and recognized, fostering broader awareness of national diversity and local governance.

Regional Clusters and Development Patterns Among Capital Cities

Examining the geographic spread of state capitals reveals striking regional clusters that reflect historical settlement patterns and economic development.The Northeast, for instance, is densely populated with capitals like Hartford (Connecticut), Dover (Delaware), and Providence (Rhode Island), cities that emerged during colonial times and evolved into administrative and commercial centers. In the Southeast, capitals such as Montgomery (Alabama), Atlanta (Georgia), and Tallahassee (Florida) cluster near major rivers and coasts, positions that historically supported agriculture, trade, and later, tourism. Midwest capitals like Lincoln (Nebraska), Des Moines (Iowa), and Sacramento (California—though technically California’s capital is Sacramento, while others like Boise and Helena anchor western expanses), tend to lie along critical transportation corridors.

“The Midwest’s capitals often occupy central or corridor positions,” explains Dr. James Whitmore, a regional historian. “This reflects both early territorial planning and the need for accessible governance in a vast, bridging region.” On the Plains, capitals such as Pierre (South Dakota), Lincoln (Nebraska), and St.

Paul (Minnesota) rise amid wide-open landscapes, symbolizing state consolidation and frontier ambition. Finally, in the Mountain West, capitals like Salt Lake City (Utah), Boise (Idaho), and Carson City (Nevada) stretch across varied topography, embodying both isolation and the dynamic energy of western expansion.

The Role of Indigenous Heritage in Capital Placement

Several state capitals carry names rooted in Indigenous languages, a testament to the deep historical presence of Native peoples long before statehood.TAH-ho-so (Jefferson, Georgia), originally used by Cherokee-speaking communities, reflects linguistic continuity despite colonial-drawn borders. In Sacramento, the name derives from the Sacramento Ranchería, a village of the Katbiame people, preserving Native echoes within modern governance. Salt Lake City’s namesake comes from the Ute word “Packit’ warnings, though commonly linked to the Mormon settlement, its original meaning reveals prior Indigenous stewardship.

These linguistic scars and echoes remind us that capitals are not just political centers but cultural crossroads. “Place names are historical documents,” says Dr. Ramirez.

“They preserve stories—some celebrated, others marginalized—of the first peoples who shaped these lands.” Modern capitals, therefore, stand at intersections of memory, identity, and governance, their names inviting reflection on the past as states move forward.

Capitals Beyond the Mainstream: Hidden Gems and Strategic Seats

While larger urban centers dominate headlines, smaller capital cities often outperform stereotypes by showcasing quiet innovation and regional influence. Annapolis, Maryland’s seat of government, boasts a 17th-century chord of colonial charm combined with a modern push in maritime policy and sustainable governance.Bismarck, North Dakota’s capital, balances large-scale planning with grassroots democratic engagement, serving as a model for mid-sized government infrastructure in expanding frontier states. Cape Canaveral, Florida, though not a traditional capital city, functions de facto as an administrative epicenter for NASA’s space operations. This unique role illustrates how capitals evolve beyond political functions into symbols of technological ambition and national identity.

Similarly, Helena, Montana’s historic Old State Capitol now houses cultural institutions, blending heritage with contemporary civic life. Capitals like Juneau (Alaska) — accessible only by air or sea — highlight logistical realties, while Helena’s riverfront location underscores geographical constraints shaping urban form. These lesser-known seats remind us that state capitals are as much about function and environment as they are about alphabetical order.

Geographic Extremes: Capitals at the Edges of America

The A-to-Z sequence includes capitals situated at the geographic farthest points of the continental and island states. Cape Canaveral (Florida), now globally synonymous with space launches, stands at 28°42′N, anchoring America’s space ambitions on America’s eastern seaboard. In the entirety of U.S.capitals, Cape Canaveral holds the southernmost position, a place where American innovation reaches beyond Earth’s bounds. More remarkably, **Honolulu**, Kapohi (Hawaii), ranks as the westernmost state capital on the continent. Nestled on Oʻahu, its stoplongest in westward coverage than any mainland city.

The distance between Portland’s misty north and Honolulu’s tropical reach—spanning nearly 2,700 miles—mirrors the country’s dramatic west-to-east span. “Hawaii’s capital embodies America’s global reach,” suggests geographer Lani Kekoa. “It’s a capital both state and node in the Pacific.” Even desert capitals like fairness—Blanchard, Nebraska (not a capital, but underscoring regional balance)—and Albuquerque’s adjacent governance nodes highlight how state capitals reflect not just political summits, but geographic conclusions, from coast to the Pacific’s edge.

Critical Facts: Fun, Stats, and Surprises in Capital Alphabetization

- There are 50 state capitals; the alphabet spans 19 letters, with half the capitals occupying the middle section (M–Z). - Only three capitals — Topeka, Sacramento, and Annapolis — start with letters A, S, and A again (repeated use), reflecting historical naming patterns. - Over half (28) of capitals have fewer than 50,000 residents, emphasizing their roles as administrative centers rather than metropolitan powerhouses.- The northernmost capital is Juneau, followed by Helena (Montana), Bismarck (North Dakota), and Dover (Delaware), illustrating a pattern of cold-weather governance. - The southernmost is Notable Key West’s “Island Capital” — though Florida’s official site is Tallahassee, Key West’s cultural capital status once tied it nationally, showing how perception expands context. Only two capitals occupy coastal waters: Annapolis (Maryland’s harbor terminus) and Honolulu (an isolated island capital), underscoring how geography shapes access and identity.

Capital Cities and Democratic Accessibility

Despite varying sizes and locations, state capitals are fundamentally anchors of democratic life. Each houses a statehouse where legislative sessions, elections, and public debate unfold—moments when citizens exercise their rights. Ranked by voter turnout, capitals like Austin (Texas), Sacramento (California), and Literally comparable, Portland (Oregon) frequently rank among the highest, indicating strong civic engagement as their seat of power.Even smaller hubs like Helena and Juneau maintain regular public forums, historic tours, and digital access—ensuring accessibility beyond urban density. “Capitals exist to serve the people,” says civic analyst Maria Chen. “Distance and size matter less than whether residents can engage, visit, and participate.” Yet disparities persist: remote or small-city capitals face challenges in funding, broadband access, and political influence, raising questions about equitable representation in federal systems.

Ongoing efforts to modernize infrastructure and expand civic outreach aim to bridge these gaps, reinforcing capitals as bridges between governance and the governed.

Mapping the Future: Capitals in a Changing America

As states grow, shift, and redefine themselves in the 21st century, their capitals evolve too — not just physically, but functionally. New seats emerge when populations expand (e.g., Heard’s move in Colorado) or when economic centers demand updated governance.Still, alphabetical order ensures continuity: **Montpelier (Vermont)** remains capital without a major highway twist; **Springfield (Illinois)** balances legacy with post-industrial reinvention. Climate resilience becomes a quiet focus: Cape Canaveral’s vulnerabilities to sea-level rise prompt adaptive planning, while inland capitals like Bismarck invest in flood mitigation. Innovation hubs such as Ann Arbor’s influence (not a capital, but nearby) inspire governance shifts near state seats.

Looking forward, the A-Z guide of state capitals reveals more than geography—it maps a living nation, where stone laid by history meets momentum of tomorrow. Each capital, whether sunny, snowy, coastal, or high-plains, is a checkpoint in America’s ongoing journey.

The Enduring Significance of Capital Geography

In the A-to-Z sequence of state capitals, every name and location tells a layered story—of settlement, struggle, strategy, and survival.From Augusta’s Civil War roots to Honolulu’s Pacific frontier, these capitals are not random markers but vital nodes in America’s federal fabric. They embody regional identities, Indigenous heritage, and democratic engagement, while physical geography shapes their form and function. Understanding this alphabetical chronicle enriches not just knowledge, but appreciation for the complexity beneath state lines.

In Washington, D.C. and nearly every corner of the country, state capitals remain the heartbeat of governance—anchored in place, reaching toward the future.

Related Post

Decoding Atypical Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Unraveling Causes, Symptoms, and Modern Management Strategies

Sophie Rain Spiderman Video: A Viral Sensation That Captivated Millions

Your October Th Zodiac Reveals Hidden Depths: More Than Meets the Eye – Boots, Stone, and Star Signs You Never Noticed

Nintendo Switch Roms Your Ultimate Guide: Unlocking Seamless Gameplay in Your Hands