Unveiling the Invisible Architecture: Decoding the Lewis Dot Structure of C2H6

Unveiling the Invisible Architecture: Decoding the Lewis Dot Structure of C2H6

Methane (C₂H₆), a simple yet profoundly influential molecule, stands at the heart of organic chemistry and global energy systems. Its molecular structure—captured through Lewis dot notation—reveals the precise arrangement of electrons that dictate bonding, reactivity, and physical behavior. Understanding the Lewis dot structure of C₂H₆ is not merely an academic exercise; it unlocks insight into how this ubiquitous compound sustains life, fuels economies, and enables innovation across industries.

By analyzing bond formation, electron distribution, and molecular geometry, we uncover the silent, atomic logic that governs methane’s role in everything from natural gas fires to carbon cycle dynamics.

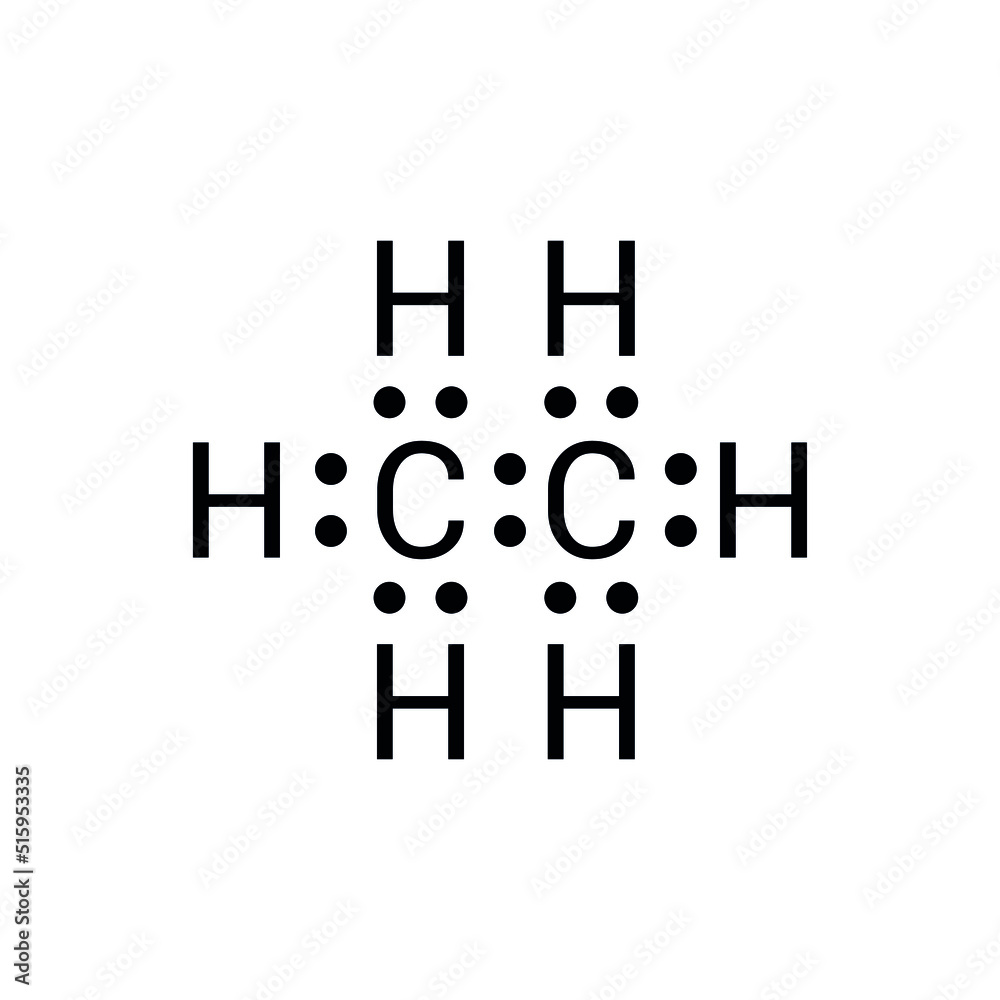

The Lewis dot structure of C₂H₆ serves as a foundational model, mapping valence electrons and connecting atoms through shared pairs—covalent bonds—while honoring the octet rule that stabilizes molecules. For methane, this visualization clarifies how two carbon atoms and six hydrogen atoms unitize to form a tetrahedral framework, each bond a delicate balance of attraction and repulsion. What emerges is not just a static diagram, but a dynamic representation of electron sharing that fuels methane’s chemical behavior and environmental impact.

The structure begins with carbon, a group 14 element with four valence electrons.

In methane, each of the two carbon atoms uses two electrons to form two distinct C–H single bonds, resulting in a square planar arrangement around each center. Hydrogen, a group 1 element with one valence electron, contributes six dots—three per hydrogen atom—representing shared pairs formed via covalent bonds. The resulting configuration centers carbon atoms in a tetrahedral geometry, with bond angles approximating 109.5°, consistent with sp³ hybridization.

This precise geometry minimizes electron pair repulsion, stabilizing the molecule and defining its shape.

The Lewis dot formula for methane—C···H–H–C···H–C···H—may appear deceptively simple, yet it encodes profound physical and chemical properties. The single bonds between carbon and hydrogen reflect a local electron dance: each pair, shared atoms contribute one electron each, forming stable σ (sigma) bonds. These bonds, though strong enough to resist casual disruption, allow methane’s molecule to remain intact under standard conditions—explaining its reliability as a fuel.

Yet the same bonds are sensitive to catalytic change, enabling reactions like combustion and methanation that drive energy and material production.

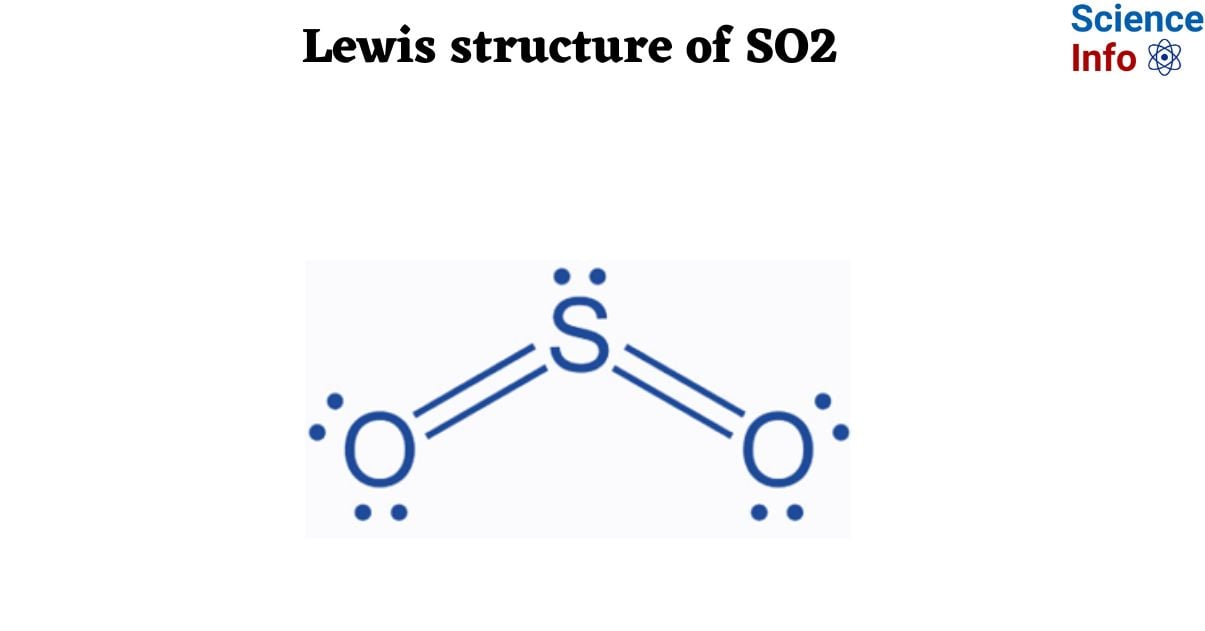

Beyond geometry, the electron distribution in C₂H₆ reveals key insights into polarity and reactivity. Unlike polar molecules such as water, methane’s symmetric tetrahedral structure results in a nearly uniform electron cloud; dipole moments cancel out, yielding a nonpolar molecule. This symmetry underpins methane’s insolubility in water and low solubility in polar solvents—a trait critical for natural gas storage, where methane migrates efficiently through pipelines.

Yet the molecule remains reactive under high-pressure or catalytic conditions, where lone electron pairs facilitate bond cleavage and transformation.

Bonding Mechanics: The Covalent Dance in C₂H₆

At the heart of methane’s stability lies the covalent bond—an intricate electron-sharing mechanism revealed through Lewis representation. In each C–H interaction, a carbon atom donates two electrons, and each hydrogen accepts one, forming a shared pair. This pairing satisfies both atoms’ valence needs, with carbon achieving a stable octet (eight electrons) and each hydrogen attaining a duplet.

The tetrahedral geometry—enforced by sp³ hybrid orbitals—positions hydrogen atoms at 109.5° angles, minimizing repulsion and maximizing bond strength. This cloning of electron sharing not only stabilizes C₂H₆ but also serves as the building block for more complex hydrocarbons and organic reactions.

Electron Counting Rules and Octet Stability

Understanding methane’s electron count requires adherence to the octet rule and formal charging principles, cornerstones of Lewis dot structure validation. Carbon, with four valence electrons, needs four more to complete its octet.

By forming two C–H bonds—two shared pairs—carbon contributes two electrons toward this goal, while each hydrogen provides one. Total shared electrons: four (two from carbon, two from hydrogen), resulting in octets for both atoms. No formal charge accompanies this arrangement (each carbon: 4 – 4 = 0; each hydrogen: 1 – 1 = 0), signaling electronic balance.

Any deviation from this ideal, such as expanded octets or formal charges, would render the structure unstable—defenses methane avoids in its stable, low-energy configuration.

Geometric Precision: Tetrahedral Symmetry and Bond Angles

Methane’s tetrahedral geometry, with bond angles near 109.5°, is more than a numerical curiosity—it guides reactivity and intermolecular behavior. This precise spatial arrangement arises from sp³ hybridization, where carbon’s 2s and three 2p orbitals merge into four equivalent hybrid orbitals oriented tetrahedrally. The angles reflect flipped ideal geometry, minimizing repulsive electron pairs around the central carbon.

Such symmetry ensures uniform dispersion of electron density, enhancing methane’s chemical inertness under ambient conditions while allowing controlled reactivity under specific catalytic conditions, crucial for applications in fuel utilization and industrial synthesis.

Physical Properties and Environmental Relevance

The molecular architecture of C₂H₆ profoundly influences its macroscopic behavior. With four valence electrons per carbon and six shared with hydrogen, methane’s low boiling point (-161.5°C) stems from weak van der Waals forces between nonpolar molecules, enabling easy vaporization. This trait makes natural gas a mobile, transportable energy carrier.

Still, methane’s environmental footprint is significant: as a greenhouse gas with over 25 times the warming power of CO₂ over a century, its stability—a direct result of symmetric bonding—prolongs atmospheric residence, amplifying climate impacts. Yet methane’s reactivity under technological intervention—catalytic oxidation or methanotrophy—offers pathways for mitigation and sustainable use.

Reactivity and Transformation: Methane’s Hidden Potential

Though methane’s tetrahedral symmetry cements its stability, the molecule harbors latent reactivity. The C–H bonds, though strong, can break under high temperature, light, or catalysts—triggers for combustion or chemical conversion.

In contrast, the C–C bond is absent in methane, limiting direct symmetry-breaking but enabling synthetic transformation via radical mechanisms. Industrial processes leverage these pathways: steam reforming converts methane to hydrogen and CO₂, while methanation builds hydrocarbons from carbon and hydrogen. Understanding Lewis dot structure clarifies which bonds—C–H or transiently activated C–C—may engage, enabling smarter, greener transformations.

The Lewis dot structure of C₂H₆, though deceptively simple, serves as a gateway to understanding one of Earth’s most consequential molecules.

It reveals not just static electron counts but dynamic bonding, geometry, and environmental interactivity. From fuel to foriness, methane’s behavior is coded at the atomic level—written in electron pairs, shaped by sp³ orbitals, and stabilized by symmetry. As science advances toward decarbonization, deep insight into such structures becomes indispensable, empowering precise manipulation of methane’s legacy for a sustainable future.

Related Post

Unveiling The Fortune: Hayes MacArthur's Net Worth And Financial Secrets

Understanding Workplace Safety: Key Principles, Practices, and the Power of Aixsafety Answers

Who Attended Beth Chapman’s Funeral: The Children Stand in Grief

Unlocking the Hidden Blueprint of Wealth: The Secret Doctrine of Financial Mastery