Unlocking Rotational Dynamics: How Moment of Inertia Shapes Engineering, Sports, and Spaceflight

Unlocking Rotational Dynamics: How Moment of Inertia Shapes Engineering, Sports, and Spaceflight

At the heart of rotational mechanics lies a deceptively simple yet profoundly powerful concept: the moment of inertia. This fundamental property quantifies an object’s resistance to changes in its rotational motion, much as mass governs linear acceleration. From the precise gyroscopes stabilizing satellites to the biomechanics influencing an athlete’s spin, moment of inertia dictates how energy moves through rotation.

Understanding its mathematical formulation—not just as an abstract number, but as a critical design parameter—opens deep insight into mechanics across disciplines.

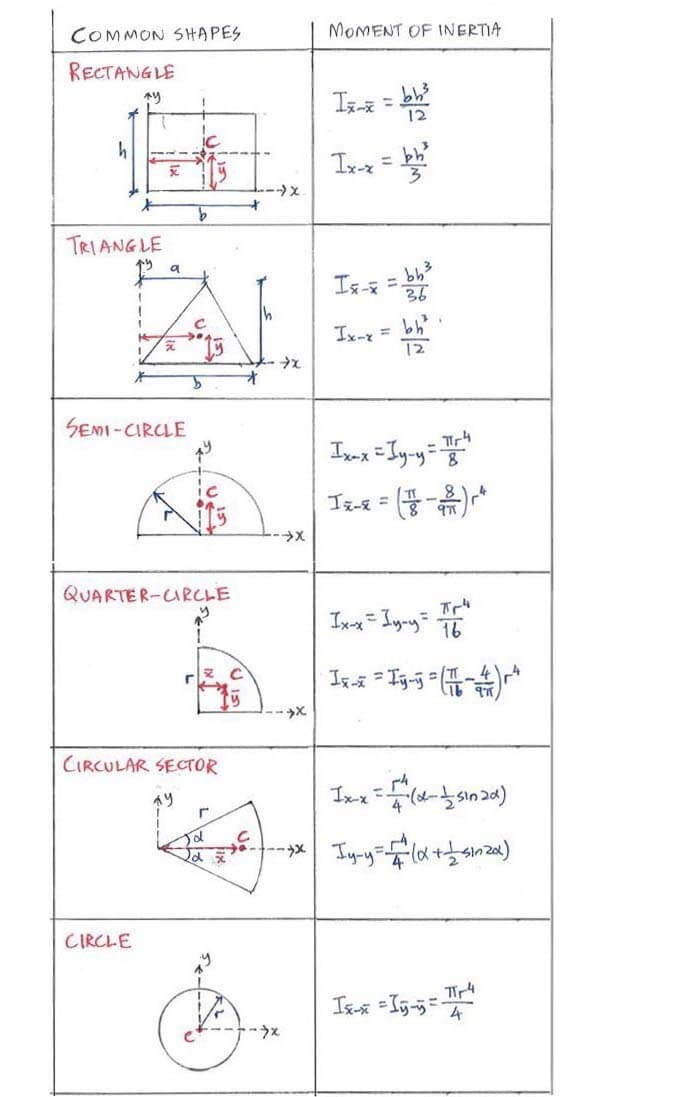

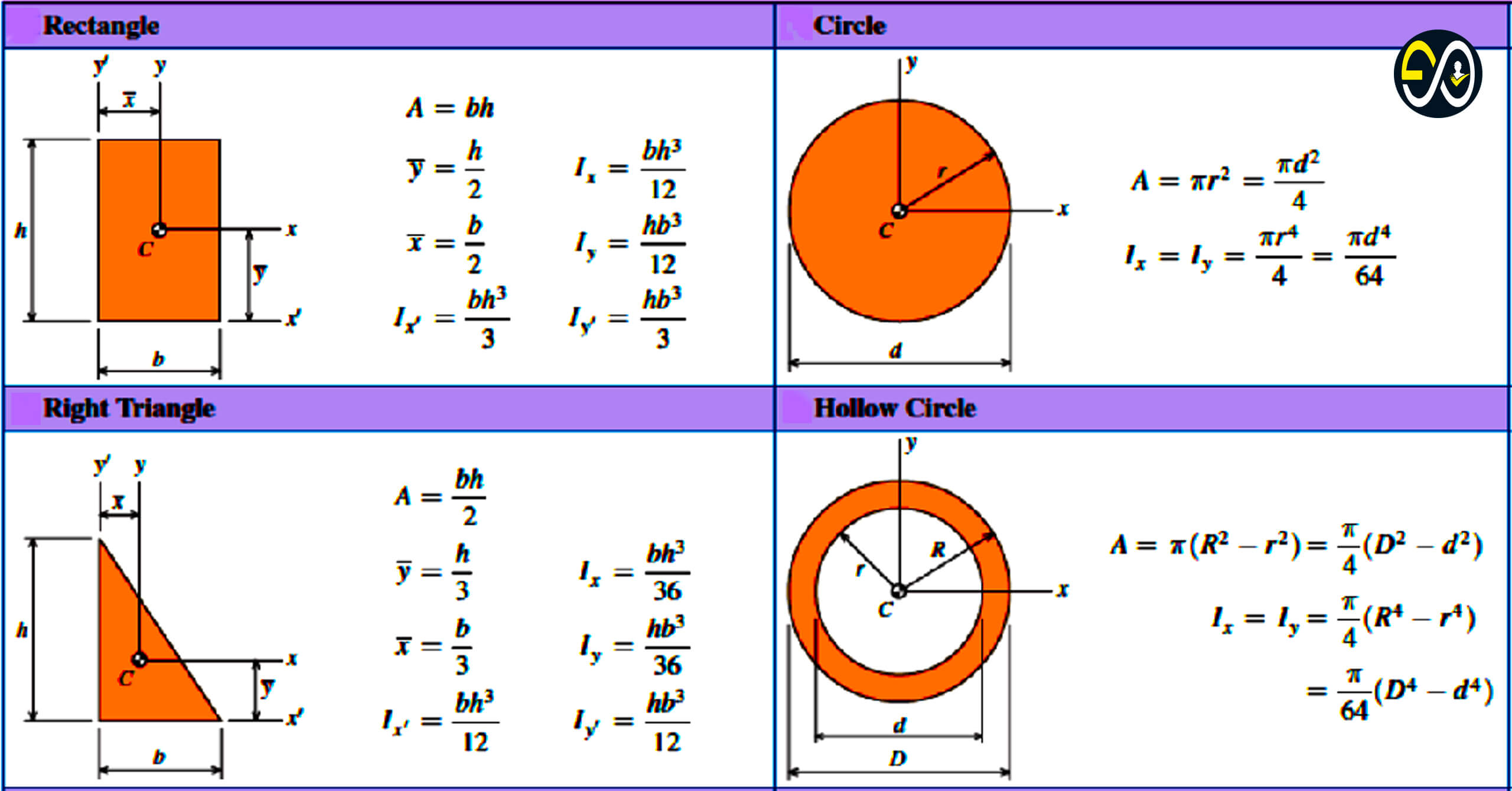

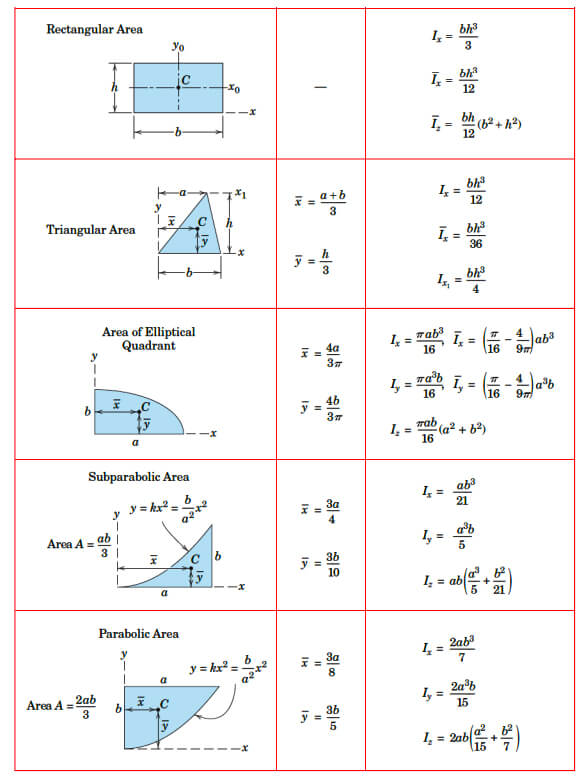

At its core, the moment of inertia (I) represents how distributed mass around an axis of rotation affects rotational resistance. For named geometries, standard formulas exist—each encoding insight into mass distribution.

Rotational inertia is not merely about total mass, but how that mass is spatially arranged. As physicist Leonhard Euler noted, “Inertia in rotation is not a simple extension of linear inertia; it depends critically on the axis and distribution.” This principle underpins modern structural engineering, biomechanics, and aerospace design.

Mathematical Foundation: The Moment of Inertia Formula Explained

The general expression for moment of inertia for a continuous mass distribution is defined by the integral: I = ∫ r² dm where r is the perpendicular distance from the mass element dm to the axis of rotation, and the integral spans the entire object’s volume.This formulation reflects a core truth—rotational resistance grows with both distance from the axis and the magnitude of mass, weighted by the square of the lever arm. For discrete point masses, the definition simplifies elegantly: I = Σ mᵢ rᵢ² Here, mᵢ represents individual masses, and rᵢ their distance from the axis. This discrete form powers calculations in mechanical systems ranging from rotating machinery to human joints.

By expressing inertia as a function of mass and position, engineers and scientists gain a precise tool to predict rotational behavior.

For common geometric shapes, standardized formulas emerge from integrating the basic definition over symmetric or analytically solvable mass distributions. These formulas serve as the backbone of technical design and analysis.

Standard Geometric Formulas: Resistance in Shape and Structure

Engineers and physicists rely on well-established moment of inertia values for fundamental shapes, enabling rapid preliminary design. These constants reflect symmetry and mass distribution: - **Solid Cylinder**: Rotating about its central longitudinal axis, I = (1/2)MR². This value—half that of a disk—explains why cylinders are preferred in shaft applications, balancing strength and rotational efficiency.- **Hollow Cylinder**: I = MR², significantly larger than its solid counterpart due to mass distributed farther from the axis. - **Solid Sphere**: I = (2/5)MR², optimal for centralized mass; yet its symmetry yields low rotational resistance, making it preferable in precision rotating systems. - **Pulley (Ring vs.

Disk)**: A thin ring has I = MR², while a solid disk (I = (1/2)MR²) stores more energy near the center—ideal for maximizing kinetic energy in toroidal mechanisms. - **Rectangular Plate**: I = (1/12)(ma² + cb²), where a and b are width and height. Symmetry leads to equal distribution of rotational resistance across principal axes: I = (1/4)(ma² + cb²).

- **Thin Rod (About Center)**: I = (1/12)ML², a staple in beam dynamics and flywheel design, where low moment of inertia enables rapid acceleration. Each formula reveals a key principle: symmetry reduces rotational inertia; mass concentrated at greater distances increases resistance. These insights guide decisions from consumer product design to spacecraft gyroscopes.

For non-standard geometries, numerical methods—such as finite element analysis—integrate discretized mass and geometry, expanding the applicability of inertia calculations beyond elementary shapes.

Applications Across Disciplines: From Spaceships to Sprinting

Moment of inertia is far more than a theoretical construct—it is a cornerstone of functional engineering. In space exploration, the momentum of inertia governs satellite pointing and orbital maneuvers.Satellites use gyroscopes and control moment gyroscopes (CMGs) whose response depends directly on moment of inertia distribution. A larger I increases the torque required for angular reorientation, demanding precise actuator control. Missions like NASA’s Artemis rely on accurate inertia modeling to stabilize lunar landers and rovers.

In mechanical engineering, rotating components such as flywheels and turbines are optimized using I formulas to balance energy storage and response time. High-I inertia flywheels smooth power delivery in hybrid vehicles, storing rotational energy efficiently. Conversely, lightweight performance gearboxes minimize inertia to enhance acceleration—critical in industrial robotics and high-speed machinery.

Biomechanics offers another vivid example. Athletes exploit moment of inertia intuitively: a figure skater pulling arms inward reduces I, spinning faster due to angular momentum conservation (L = Iω). Similarly, gymnasts and divers manipulate body configuration to control rotation mid-air. “Rotational dynamics are invisible but omnipresent,” explains Dr. Elena Torres, biomechanics researcher at MIT. “Understanding inertia lets athletes fine-tune technique for precision and power across sports like diving, figure skating, and tennis serves.” In aerospace, flight dynamics depend on moment inertia. A aircraft’s longitudinal and lateral I values determine pitch control authority. Smaller I about the longitudinal axis allows faster roll response—critical during maneuvers—while precise I values ensure stability and fuel efficiency. Satellites use variable inertia through movable masses (like gravitational gradient control) to maintain orientation without propellant. These dynamic adjustments rely on predictive models rooted in moment of inertia formulas. Traditional machinery, such as electric motors, leverages I to balance performance and durability. Low-I materials like carbon-fiber rotors minimize inertia without sacrificing strength, enabling rapid start-up and energy efficiency. This principle extends to renewable energy, where wind turbine blades are engineered for optimal inertia—capturing energy smoothly while resisting fatigue. Furthermore, digital simulations now embed inertia modeling at scale. Finite element analysis (FEA) software lets designers predict I for complex parts, integrating real-world variability and thermal effects. This advancement accelerates innovation across industries—from micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) to heavy industrial gearboxes. Mathematical Depth and Computational Considerations

Beyond geometry, moment of inertia calculations increasingly involve multidimensional and temporal dynamics. Rotational inertia may vary with speed in anisotropic materials or under variable loads—challenging static models.

Advanced analytics integrate stress-strain behavior and temperature effects, particularly in aerospace and nuclear engineering. Modern engineering software employs numerical integration and Monte Carlo methods to account for uncertainty in

Related Post

DruskiPointingAtHimself: What a Symbol Reveals About Personality, Identity, and the Power of Self-Expression

Who Is Rachelle Ferrell’s Husband? Unveiling the Life Behind the Name

From Backstage to Bold Front: How Alisa Amore Rose to Stardom in the Adult Industry

Travis Fimmel and His Wife: A Quiet Power Behind The Global Spotlight