Unlocking Atomic Secrets: What Is a Mass Number and Why It Matters

Unlocking Atomic Secrets: What Is a Mass Number and Why It Matters

At the heart of modern chemistry and physics lies a precise, foundational concept: the mass number. Defined as the total count of protons and neutrons within an atomic nucleus, the mass number—denoted by the symbol A—serves as a cornerstone in understanding elemental identity, isotopic variation, and nuclear behavior. More than just a numerical value, this number reveals how atomic stability, energy release, and chemical interactions unfold at the subatomic level.

For scientists, educators, and students alike, grasping the mass number is essential to interpreting the building blocks of matter.

The mass number, mathematically expressed as A = Z + N, where Z is the atomic number (protons) and N is the neutron count, allows nuclear physicists to categorize isotopes—atoms of the same element with differing neutron numbers. For example, carbon-12, the most stable form, contains six protons and six neutrons (A = 12), while carbon-14, used in radiocarbon dating, has six protons and eight neutrons (A = 14).

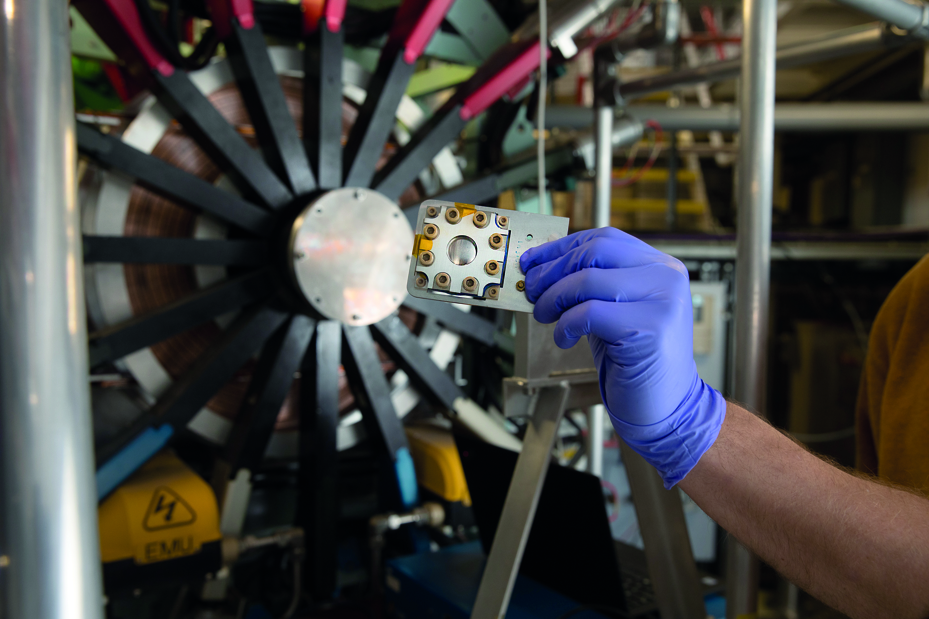

This difference in N fundamentally alters nuclear stability and decay patterns. As physicist Dr. Elena Marquez puts it, “The mass number isn’t just a label—it’s a fingerprint of an atom’s nuclear inventory, revealing how it may decay, bond, or power celestial processes.” Understanding mass number enables precise interpretation of nuclear reactions, from energy production in stars to medical imaging techniques like PET scans.

In stars, fusion of hydrogen isotopes into helium—where helium-4 has A = 4 via 2 protons and 2 neutrons—drives stellar luminosity and longevity. In medicine, isotopes such as technetium-99m (A = 99) are carefully selected for diagnostic imaging based on their nuclear properties tied directly to their mass number.

To visualize the significance, consider a taxonomic analogy: just as species are defined by chromosomes, atoms are defined by mass number.

Each isotope of an element shares identical proton count—representing identity—but differs in neutron sum, unlocking variability in behavior and utility. For instance: - Oxygen-16 (A = 16): stable, abundant, and vital for respiration. - Oxygen-18 (A = 18): heavier, used in paleoclimate studies to trace water movement over millennia.

- Uranium-235 (A = 235): enriched and fissile, fueling nuclear reactors and weapons. These variations, governed strictly by mass number, dictate how elements interact in both natural and engineered systems. In nuclear medicine, selecting the right isotope—like iodine-131 (A = 131), used to treat thyroid disorders—depends on precise control over atomic mass properties to maximize therapeutic effect while minimizing radiation damage.

The Role of Mass Number in Isotope Behavior

Isotopes of the same element share identical electron configurations—preserving chemical identity—but differ in nuclear mass, influencing physical behaviors such as diffusion rates, vapor pressure, and biological distribution. This divergence stems from the extra neutrons, which increase nuclear size without altering chemical reactivity. For example, deuterium (D or H-2, A = 2), a stable isotope of hydrogen, exhibits slower molecular motion in water compared to protium (H-1, A = 1), a key reason it

Related Post

Outdoor Games: The Ultimate Fusion of Fitness and Fun That Keeps Kids (and Adults) Moving

Vicky Nguyen NBC Bio: Age, Husband, and the Public Image Behind the Spotlight

The Grind of Time: How The Old Man Cast Defines Resilience in a Vanishing World

Jackson Wyoming’s Elevation: A High-S Warscape Towering Above the Rockies at 6,300 Feet