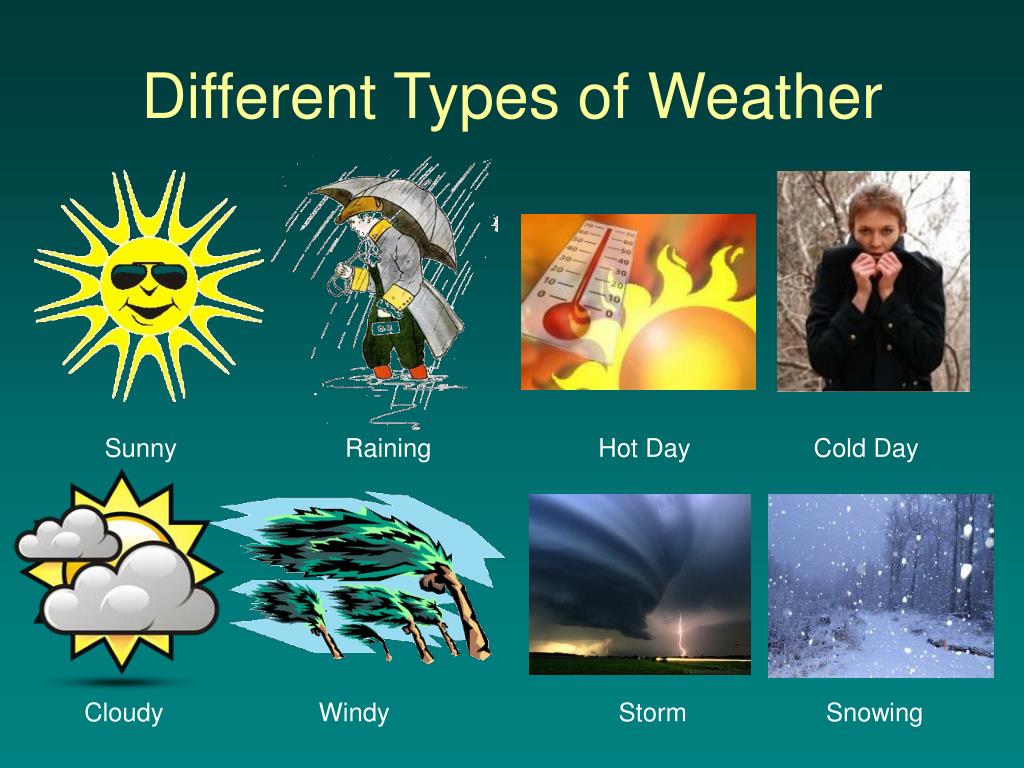

Understanding Different Types of Weather: A Comprehensive Guide to Nature’s Most Dynamic Forces

Understanding Different Types of Weather: A Comprehensive Guide to Nature’s Most Dynamic Forces

Weather is far more than just a daily forecast— it is a dynamic, ever-changing system that shapes ecosystems, influences agriculture, and impacts daily life across the globe. From the blistering heat of a midday sun to the frigid grip of polar storms, each type of weather reflects complex atmospheric interactions governed by temperature, pressure, humidity, and moisture. This guide dives deep into the most prevalent weather phenomena, explaining their formation, characteristics, and real-world effects—equipping readers with the knowledge to interpret the skies with clarity and precision.

Fog: The Invisible Veil of Low Visibility

Fog is a ground-level cloud of tiny water droplets or ice crystals suspended in the air, reducing visibility to less than 1 kilometer. Unlike mist, thick fog implicates serious disruptions—especially in transportation and navigation. Meteorologists classify fog into several types based on formation: - **Radiation fog**: Develops overnight under clear skies and calm winds when ground radiates heat; most common in valleys during autumn and winter.- **Advection fog**: Occurs when warm, moist air moves over a cooler surface, such as ocean breezes encountering cold land, typical in coastal regions. - **Sea fog**: A specialized form of advection fog common along fog-prone coasts like California’s San Francisco Bay. - **Upslope fog**: Forms when moist air is forced upward along elevated terrain, cooling adiabatically.

> “Fog can reduce visibility to zero within minutes, turning routine commutes into hazardous conditions,” notes Dr. Elena Vasquez, a senior meteorologist at the National Weather Service. “Understanding its types helps communities issue timely warnings and protect lives.” Driven by simple thermodynamic principles, fog’s behavior illustrates the delicate balance of air temperature, humidity, and surface conditions in shaping local weather.

Snowstorms: Winter’s Slow-Motion Catastrophe

Snowstorms are intense winter weather events defined by heavy snowfall, strong winds, and reduced visibility. Not all snowstorms carry equal threat—classification hinges on snowfall rates, duration, and wind-driven snow accumulation. Two primary categories define most snowstorms: - **Heavier snowstorms**: Accumulation exceeding 10 cm (4 inches) in 12 hours, often driven by powerful low-pressure systems known as “blizzards.” - **Lake-effect storms**: Locally intense snowfall downwind of large lakes, where cold air sweeps over relatively warm water, supercharging snow output in narrow bands—common around the Great Lakes.Anticyclones dominate clear winter skies, but when seas of cold air collide with moisture-laden flows, explosive cyclogenesis can trigger dangerous snowstorms. Wind speeds exceeding 35 mph compound danger, creating whiteout conditions and increasing risks of hypothermia and infrastructure damage. > “Snowstorms are more than just accumulation—they’re a complex blend of temperature, wind, and geography,” says climate physicist Dr.

Raj Mehta. “Modeling these variables allows forecasters to predict not just snowfall totals, but where and when blizzards will strike hardest.” From triggering school closures to stranding travelers, snowstorms demand a multidimensional understanding rooted in both atmospheric science and regional topography.

Thunderstorms: The Power of Atmospheric Electrification

Thunderstorms are rapid bursts of convective energy fueled by intense solar heating, moisture, and atmospheric instability.These storms generate dramatic visual displays—flashes of lightning, booming thunder—and pose serious risks including flash floods, hail, and tornadoes. Key ingredients for thunderstorm formation: - A moist, unstable air mass near the surface - A lifting mechanism such as fronts, terrain uplift, or daytime heating - Sufficient wind shear to organize storm cells Classification by severity includes: - **Single-cell thunderstorms**: Short-lived, weak storms typical in the tropics with minimal damage. - **Multicell clusters**: Lines or complexes of storms, often producing widespread, moderate rainfall and gusty winds.

- **Supercells**: Violent, long-lived storms with rotating updrafts capable of spawning tornadoes, large hail, and damaging winds. “Supercells represent nature’s most powerful thermodynamic reactor,” explains differently physicist Dr. Maya Thompson.

“Their rotating updrafts sustain extreme energy, allowing severe weather phenomena to persist far longer than ordinary storms.” From sudden hail impacts to rare tornado touchdowns, thunderstorms exemplify the sky’s untamed power and the necessity of accurate, real-time monitoring.

Tornadoes: Swift Strikes of Rotating Force

Tornadoes are violently rotating columns of air extending from a thunderstorm to the ground, capable of obliterating homes and uprooting entire forests in seconds. Defined by wind speeds exceeding 100 mph, tornadoes form under highly unstable, wind-sheared conditions often tied to powerful supercell storms.Conditions conducive to tornado development: - Strong vertical wind shear: Changing wind speed and direction with height to generate rotation. - High instability: Warm, moist air near the surface capped by cooler air aloft, triggering explosive upward motion. - A strong lifting mechanism—such as a dry line or cold front—to initiate storm rotation.

> “Tornadoes are among the most unpredictable and deadly weather phenomena,” states Dr. Linda Cruz, a leading atmospheric researcher at NOAA. “Their formation is sensitive to minute changes in temperature and wind profiles—making precise forecasting an ongoing scientific challenge.” While tornado warnings typically offer only minutes of lead time, advancements in Doppler radar and storm tracking have improved detection and response, saving countless lives.

Understanding the mechanics behind these rotating tempests enables communities to prepare and reduce vulnerability.

Hurricanes and Cyclones: Titans of the Tropical Oceans

Hurricanes (Atlantic and Northeast Pacific) and cyclones (South Pacific and Indian Ocean) are massive, rotating storm systems fueled by warm ocean waters above 26.5°C (80°F). These tropical cyclones draw energy from thermal heat and evaporative processes, growing into intense threats with storm surges, torrential rain, and sustained winds exceeding 74 mph.Structural components include: - The eye: A relatively calm, clear center surrounded by the fierce eyewall of extreme winds and heavy rain. - The eyewall: Where most damage occurs, with vertical updrafts reaching over 15 km in height. - Outer rainbands: Sesame-shaped bands wrapping toward the center, producing widespread flooding.

Hurricanes follow a lifecycle beginning as tropical depressions, intensifying over warm seas, then potentially strengthening into major hurricanes with Category 3 ratings or higher. Climate change is altering storm patterns—expectations increasingly factor in rising sea temperatures and shifting tracks. > “Cyclones are powerful reminders of how ocean-atmosphere coupling shapes global weather,” says Dr.

Amir Patel, a meteorologist specializing in tropical systems. “Monitoring their development is critical—especially as warmer seas intensify their destructive potential.” Forecasting hurricane paths and intensity remains a complex blend of oceanic data, satellite imagery, and atmospheric models, vital for coastal preparedness and mitigation.

Extreme Heat Events: When Heat Dominates the Sky

Defined by prolonged periods of abnormally high temperatures, extreme heat events pose serious public health risks, strain energy grids, and degrade air quality.These episodes are increasingly frequent and intense due to climate change and urbanization. Factors intensifying heatwaves include: - Persistent high-pressure ridges: Trapping warm air beneath stable atmospheric layers. - Urban heat islands: Where concrete, asphalt, and reduced green space amplify ambient temperatures by several degrees.

- Low humidity: Facilitating rapid heat exhaustion due to impaired sweating. The health impacts are severe: heatstroke, dehydration, cardiovascular stress—especially among the elderly, children, and outdoor workers. In cities like Phoenix and Istanbul, heat alert systems now trigger cooling centers and public advisories.

> “Heat is not just uncomfortable—it’s dangerous, and spaces with limited access to cooling are increasingly vulnerable,” warns Dr. Simone Liu, a public health expert at WHO. “Understanding heatwave behavior through climate modeling helps cities build resilience.” Emerging strategies such as green roofs, reflective surfaces, and targeted warning systems are proving essential in reducing heat-related harm.

Droughts: The Slow Onset of Weather Extremes

Droughts represent a prolonged absence of normal precipitation, disrupting agriculture, water supply, and ecosystems. Often overlooked until they escalate, droughts develop gradually and can span months or years, affecting vast geographic regions. Classifications include: - **Meteorological drought**: Measured by

Related Post

Karens, Turtleboy, and the TurtleSnipe: How a Twitter War Sparked a Racial Rep excellence Acid Test

Where Is Jackson Hole? The Alpine Gem Nestled in Wyoming’s Natural Wonderland

Mastering Letter S Sample 4 Session 6: The Key to Unlocking ELS Reference Skills

Who Is Kético: The Rock’s Long-Lost Twin Brother and His Surprising Legacy