The Molecular Architect: Understanding the Monomer of a Protein

The Molecular Architect: Understanding the Monomer of a Protein

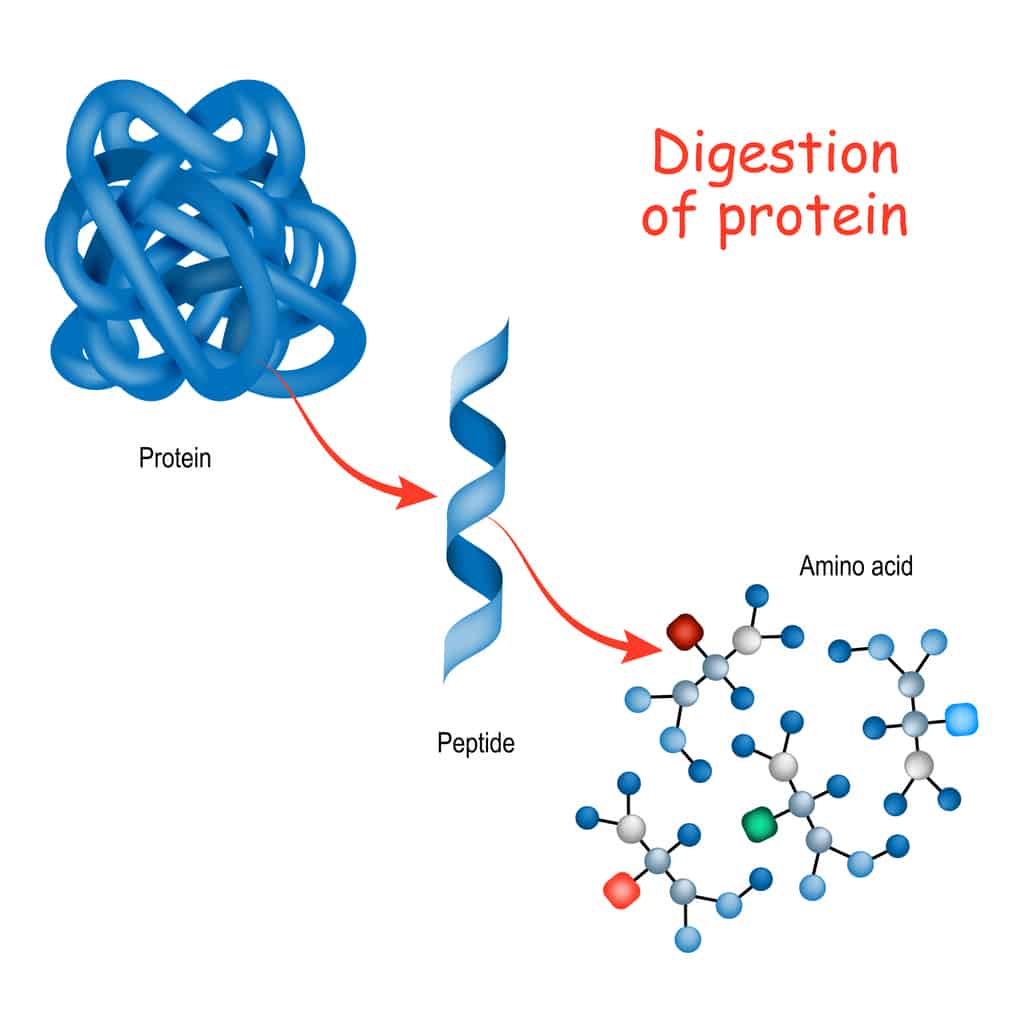

The monomer of a protein is the simplest structural unit—a single polypeptide chain composed of amino acids linked by peptide bonds. Each amino acid contributes distinct chemical properties—hydrophobic, hydrophilic, acidic, or basic—that collectively shape the folding patterns and functional capabilities of the final protein. As biochemist Dr. Jane Kim notes, “The monomer is not merely the start of a chain; it is the foundation upon which a protein’s identity, function, and interaction with the world are constructed.” Amino acids—twenty in nature—are the raw units that assemble into monomers through covalent peptide bonds, forming a linear sequence governed by the genetic code. This primary structure determines how the monomer will fold and interact, effectively encoding biological function into molecular architecture. The precise order of amino acids, encoded in DNA and RNA, ensures precision at the nanoscale, where even a single substitution can disrupt activity—illustrating the monomer’s central role in molecular fidelity. While often viewed as a static unit, the monomer serves as a dynamic platform for functional complexity. Proteins rarely act alone; their monomeric nature enables association with others to form oligomers—multimeric complexes with specialized roles. Hemoglobin, for instance, comprises four distinct monomers each binding oxygen, demonstrating how monomer versatility underpins systemic function. This multimeric assembly is essential in enzymes, receptors, and structural proteins, where cooperative interactions amplify biological responsiveness. Consider the monomer’s adaptability in enzymatic catalysis: each amino acid in the chain can occupy active sites with precise spatial orientation, enabling substrate binding and chemical transformation. A single monomeric error—like a missense mutation—may impair this process, underscoring the fragility and significance of monomeric precision. Research on cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) proteins reveals how monomer misfolding can halt function, leading to disease. Protein monomers power nearly every biological process, acting as motors, sensors, catalysts, and structural scaffolds. Their modular design allows cells to deploy tailored molecular tools with remarkable efficiency. Take actin, a motility monomer that assembles into filaments driving cell movement and contraction—its continuous polymerization enables dynamic cytoskeletal rearrangement critical for tissue dynamics.From Amino Acids to Functional Monomer

Dynamic Diversity: From Monomer to Multifunctionality

The Role of Monomers in Cellular Machinery

Monomers also play a pivotal role in cellular regulation and signaling.

Hormones like insulin operate not as singular molecules but as aggregates of monomer-derived units, their activity tightly controlled by equilibrium and compartmentalization. This controlled behavior ensures signals remain localized and responsive, preventing systemic overload.

Structural Precision and Functional Consequences

The peptide backbone’s geometry combined with diverse R-group chemistry dictates folding pathways.

For example, proline’s rigid cyclic structure introduces bends, while glycine allows flexibility—each monomer influencing global fold. Misfolding at this level triggers misregulation, linked to degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, where aberrant monomer aggregation disrupts neuronal function.

- Charge Distribution: Acidic and basic residues mediate salt bridges, stabilizing folded states.

- Hydrophobic Core Formation: Nonpolar side chains cluster inward, minimizing solvent exposure and reinforcing tertiary structure.

- Disulfide Bonds: Covalent links between cysteine residues in some monomers crosslink chains, enhancing thermal resilience.

Eroing monomeric function is key to drug development and therapeutic design. Targeting specific monomer residues allows precision medicine approaches—such as kinase inhibitors blocking mutant enzymes in cancers—where altering monomer activity reshapes disease progression.

Engineering Life: The Monomer’s Role in Biotechnology

In biotechnology, monomers are not just studied—they are engineered.

Recombinant DNA technology enables designers to assemble novel monomers with custom amino acid sequences, crafting proteins with enhanced properties. These engineered monomers drive advances in enzyme catalysis, biosensors, and regenerative medicine, exemplifying how deep understanding of monomeric fundamentals accelerates innovation.

Synthetic biology further leverages monomer modularity, assembling artificial proteins from designed building blocks to mimic or surpass natural functions. Such efforts hinge on predictable monomer behavior, revealing how foundational protein science enables molecular innovation at scale.

The monomer, though a single structural unit, is indispensable.

It embodies the convergence of chemistry, physics, and biology, translating genetic information into life’s functional machinery. From catalyzing life-sustaining reactions to enabling cutting-edge medical therapies, the monomer remains the unsung hero of molecular biology—small in size, yet colossal in impact.

Understanding the monomer’s dual role—as both structural unit and functional catalyst offers profound insight into the elegance of biological design. As scientific exploration continues, unraveling monomer dynamics will remain central to unlocking new frontiers in medicine, biotechnology, and our comprehension of life itself.

Related Post

What Is the Monomer of a Protein? The Building Block That Builds Life

Emily Compagno’s Shuttle: A Deep Dive into Her Personal Life Beyond the Spotlight

Argentina vs. Brazil: The 26th’s Epic Battle That Redefined South American Football Rivalry

Conquer Astel: The Ultimate Guide to Victory in Elden Ring