Students For A Democratic Society: The Intellectual Fire that Ignited the New Left

Students For A Democratic Society: The Intellectual Fire that Ignited the New Left

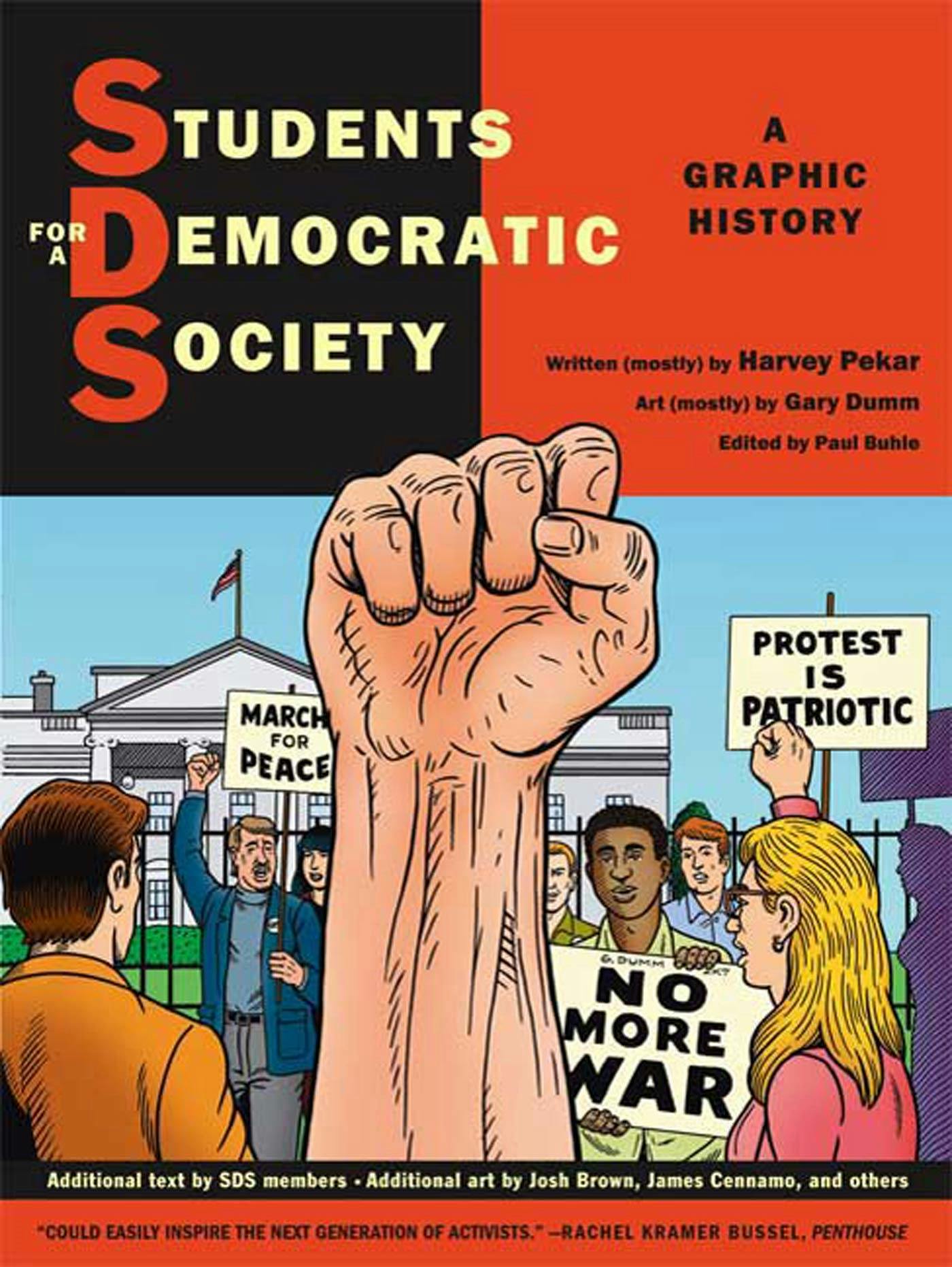

At the heart of mid-20th century American radicalism, Students For A Democratic Society (SDS) emerged not merely as a student organization, but as a transformative intellectual and political force shaped by the Students for a Democratic Society Apush definition. Defined by its foundational manifesto, *Portfires of Freedom* (1962), SDS embodied a radical call for participatory democracy, civil rights, and anti-imperialism—ideals that challenged both Cold War orthodoxy and stagnant liberal leadership. Grounded in a vision of direct citizen involvement over passive representation, SDS fused moral urgency with structural critique, positioning itself as the conscience of a generation disillusioned with institutional failure.

The SDS’s ideological framework, as articulated in its 1962 constitution, centered on participatory democracy—a principle demanding that political power be rooted in active, decentralized engagement. This was more than a slogan; it was a revolutionary reimagining of democracy itself. As Tom Hayden, the movement’s principal author of *Portfires*, declared: “Authentic democracy must allow people to shape decisions that affect their lives.” This stood in stark contrast to representative systems dominated by elites and Cold War pragmatism.

The SDS rejected tokenism, demanding mechanisms like national student conventions where decisions emerged from consensus, not top-down authority. Such ideals resonated deeply with students navigating a society fractured by racism, militarism, and political apathy, making SDS a crucible for a new generation of politically conscious activists.

Rooted in the civil rights era, SDS evolved from campus activism into a broader anti-system force.

Initially aligned with desegregation efforts and voter registration drives, the organization rapidly expanded its scope to confront U.S. foreign policy, particularly unchecked military intervention abroad. By the mid-1960s, its critique of American imperialism became central—framing Vietnam not just as a foreign war but as an extension of domestic hypocrisy.

The SDS’s 1965 “Soledad Brothers” statement, linking racial injustice to state violence, demonstrated its ability to bridge racial and class struggles under a unified moral banner. As historian James M. Gibson notes, “SDS transformed student protests into a national dialogue about democracy’s soul—whether the United States truly served all its citizens.” This expansion from campus pages to street marches and foreign policy debates marked a pivotal evolution in 1960s radicalism.

The organization’s defining document, the 1962 *Portfires of Freedom*, outlined five core demands: genuine democratic participation, civil rights for all, an end to war, economic justice, and ecological responsibility. These were not abstract goals but actionable principles aimed at dismantling systemic inequities. By framing civil rights alongside opposition to war and economic inequality, SDS reframed activism as an interconnected struggle—a holistic critique of a political-military-industrial complex entrenched in racial and class hierarchies.

The manifesto’s emphasis on “consciousness-raising” underscored SDS’s belief that meaningful change required both structural reform and deep cultural transformation. Activists urged students to become “critical citizens,” capable of analyzing power rather than merely reacting to it.

SDS’s operational style reinforced its revolutionary ethos.

Rejecting hierarchical leadership, the group embraced consensus-based decision-making and direct action. Campuses became training grounds for organizing: teach-ins, sit-ins, hunger strikes, and mass demonstrations became routine. The 1964 Mississippi Freedom Summer, co-organized with SDS and SNCC, exemplified this blend of direct action and grassroots empowerment.

Volunteers lived among Black communities, challenging voter suppression through education and silent witness—a testament to SDS’s insistence on moral visibility over media spectacle. This hands-on engagement cultivated a borderless coalition of students, civil rights leaders, and working-class Americans united by a shared demand for justice.

The movement’s trajectory reflected both its power and its limitations.

By 1969, internal divisions—over tactics, gender dynamics, and ideological purity—fractured SDS. The 1969 Chicago convention split the organization into reformist and more radical factions, mirroring broader tensions within the New Left. Yet even in fragmentation, SDS’s legacy endured.

Its participatory model influenced later movements—from environmentalism to anti-globalization—while its insistence on democratic inclusion shaped modern activism. The *Portfires of Freedom* remained a benchmark for generational dissent: “participatory democracy” not only defined SDS but still serves as a litmus test for political renewal.

Ultimately, Students For A Democratic Society was more than a student group—it was a living experiment in democratic renewal.

Defined by the *Students for a Democratic Society Apush definition*, SDS answered its era’s discontents with radical thought and relentless action. Its voice, though fractured, echoed across decades, reminding each generation that democracy is not granted, but seized, transformed, and continually reimagined from the ground up. In a time when civic trust is strained and political alienation runs high, SDS stands as both warning and blueprint: that true change begins not in Congress, but in the courage of young people refusing to accept a democracy unfulfilled.

Related Post

Unlock Apple Music Free Trial A Simple Guide

Rachel Scott Net Worth: Beyond the tragedy — A Legacy of Integrity and Quiet Accumulation

Turkey's Nuclear Arsenal: What You Need To Know – The Hidden Power Shifting Regional Dynamics

Anthony Rizzo Contract: A Case Study in Contractual Complexity and Team Rebuilding