Rotational Inertia of a Rod: The Hidden Force Behind Rotation

Rotational Inertia of a Rod: The Hidden Force Behind Rotation

Understanding rotational inertia is fundamental to unlocking the physics of spinning systems, and few simple yet powerful models illustrate this principle more clearly than the rotational inertia of a uniform rod. Whether in engineering prototypes, mechanical devices, or even natural phenomena, the way a rod resists rotational acceleration dictates everything from motor efficiency to playground swing dynamics. By examining rotational inertia through the lens of a rigid rod, we reveal how mass distribution fundamentally shapes rotational behavior—transforming abstract theory into tangible mechanics.

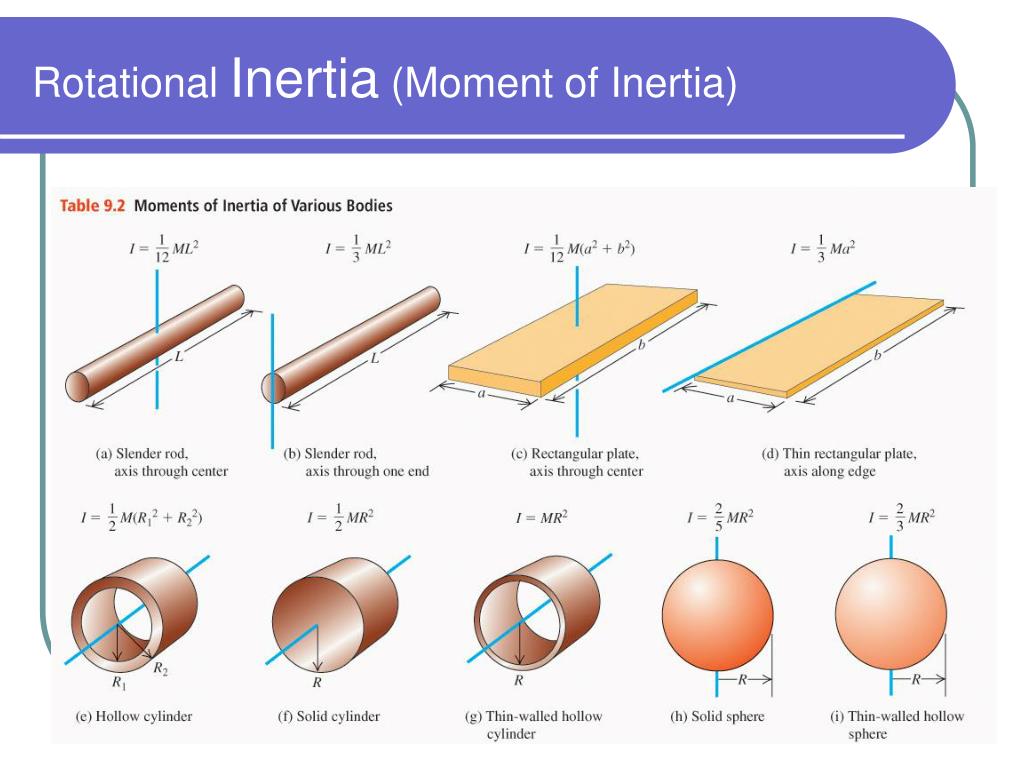

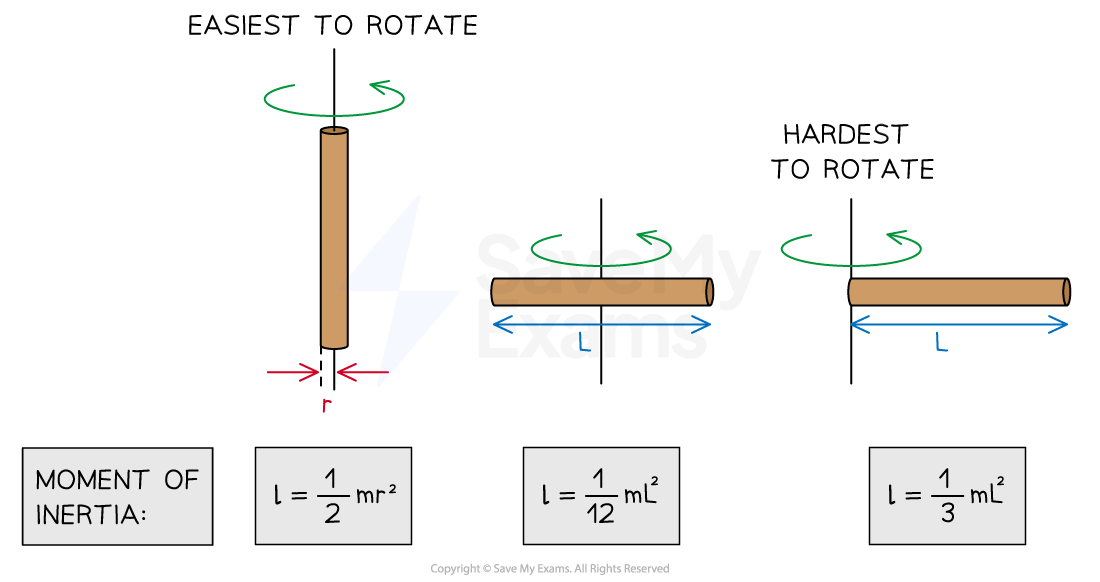

The rotational inertia, or moment of inertia, quantifies an object’s resistance to angular acceleration.

For a slender rigid rod rotating about its center, this value emerges not merely from total mass, but from how that mass is arranged relative to the axis. Unlike translational mass, rotational inertia depends critically on the perpendicular distance of mass elements from the axis. As physicist John R.

Taylor notes, “The farther mass lies from the axis, the greater the torque needed to achieve the same angular acceleration.” This deceptively simple principle governs dynamic systems across scales—from microscopic blades in turbines to macroscopic wooden dowels in vintage toys.

Mathematical Foundation: Deriving Rotational Inertia for a Uniform Rod

To compute rotational inertia, consider a thin, uniform rod of length \( L \) and mass \( M \), rotating about an axis perpendicular to its length and passing through its center. The derivation begins with the fundamental definition of rotational inertia:

The rotational inertia \( I \) is defined as \( I = \int r^2 \, dm \), where \( r \) is the distance from the axis of rotation and \( dm \) is an infinitesimal mass element. For the central-axis rotation, \( r = x \), with \( x \) ranging from \( -L/2 \) to \( L/2 \).

The linear mass density becomes \( \lambda = M/L \), so \( dm = \lambda \, dx = (M/L)\,dx \). Substituting into the integral yields:

“Using \( r = x \), the integral becomes \( I = \int_{-L/2}^{L/2} x^2 (M/L)\,dx = \frac{M}{L} \int_{-L/2}^{L/2} x^2 \, dx = \frac{M}{L} \left[ \frac{x^3}{3} \right]_{-L/2}^{L/2} = \frac{M}{L} \cdot \frac{2}{3} \left( \frac{L}{2} \right)^3 = \frac{1}{4}ML^2 \

Thus, the rotational inertia of a uniform rod about its central perpendicular axis is \( I = \frac{1}{12}ML^2 \). Remarkably, this value balances symmetry and geometry—less than half the point-mass model (\( I = MR^2 \)), yet greater than isolated point elements along the axis.

This precise balance reflects the rod’s distributed mass, offering engineers and physicists a predictable benchmark for rotational dynamics.

To appreciate how mass distribution alters rotational inertia, consider variations in axis and geometry. Rotating the same rod about an end axis—rather than its center—modifies the integral bounds and \( r^2 \) distances. For a rod rotating about one end, \( x \) ranges from \( 0 \) to \( L \), giving \( I = \frac{1}{3}ML^2 \).

This greater moment of inertia underscores a consequence: mass farther from the axis exponentially amplifies resistance. As renowned fluid dynamicist Heinrich Landau observed, “Rotational inertia is not intrinsic to mass alone, but to how that mass is spatially arranged.”

Real-World Applications: Engineering, Sports, and Everyday Mechanics

Rotational inertia of rods serves as a cornerstone in diverse engineering applications. In electric motors, rotor design leverages the rod’s moment of inertia to regulate startup torque and smoothness during acceleration—critical for applications ranging from precision robotics to high-speed fans.

Engineers manipulate rod length and material density to tune rotational resistance, optimizing for efficiency and durability.

In mechanical vibration analysis, rods model structural components where rotational stability matters. Consider crane boom segments or swing-up mechanisms in vehicles—rotational inertia dictates response to applied torques, influencing stability and energy absorption. Even in sports, the rod analogy applies: the carved wooden shaft of a bowling pin resists angular acceleration differently depending on mass distribution, affecting energy transfer and pin dynamics.

One striking example involves flywheels—rotational energy storage devices often built with elongated cylindrical rods.

Their high \( I \) enables smooth kinetic energy management, reducing mechanical fluctuations in engines. By maximizing mass at the outer radius while minimizing rotational speed, flywheels achieve efficient energy buffering. The rod remains a portable metaphor—its simple form concealing profound utility in storing and releasing motion.

From Theory to Technology: The Rod as a Gateway to Rotational Physics

Studying rotational inertia through a rod transforms abstract physics into accessible, tangible learning.

It demonstrates how foundational equations arise from symmetry and geometry, while practical implications span renewable energy systems, consumer electronics, and aerospace mechanisms. The rod’s central axis offers a controlled reference frame, enabling precise calculations and validating theoretical models used across mechanical and civil engineering disciplines.

As researchers continue to push material science and nanotechnology, the rod’s rotational inertia principle endures—scaling from macroscopic power tools to micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) gyroscopes. Its consistent behavior under variable conditions underpins predictive modeling and simulation, making it indispensable in both education and advanced research.

Ultimately, rotational inertia of a rod transcends a classroom formula—it is a testament to how even simple geometries reveal deep mechanical truths.

Understanding this resistance to rotation empowers innovation, illuminates natural motion, and bridges everyday experiences with the sophisticated technologies shaping modern life. The humble rod, governed by the quiet power of inertia, stands as a cornerstone of rotational physics.

Related Post

Te logarithms unlock math’s deepest secrets: Uncover all THR FoM Math Trf Questions

The Chronological Boyfriends List of Taylor Swift: Understanding Her Romantic Journey in Order

How Indomaret’s Tiket Campaign Makes Concert Tickets a Click Away, According to, “Beli Tiket Kai Makin Mudah Di Dapatkan”

Fiza Chaudhary Viral MMS: The Untold Story Behind the Controversy That Shook Literary Circles