Prototype Definition Psychology: How Mental Blueprints Shape Our Perceptions and Decisions

Prototype Definition Psychology: How Mental Blueprints Shape Our Perceptions and Decisions

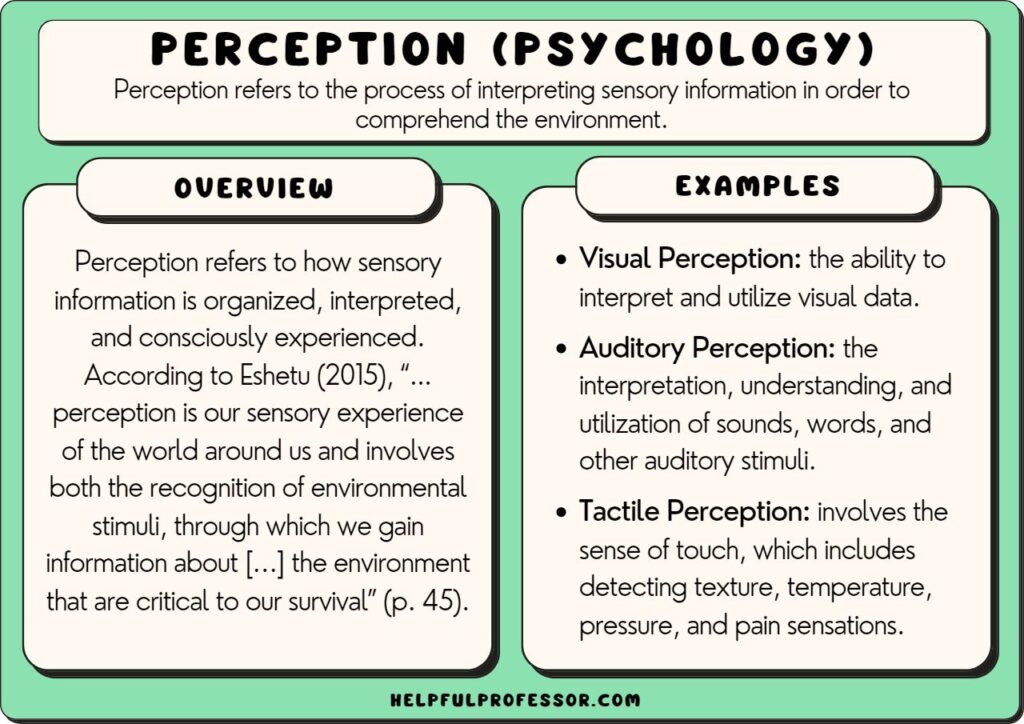

At the core of how humans interpret the world lies a silent, invisible force—the prototype. Defined within the framework of prototype definition psychology, prototypes are mental blueprints formed from repeated experiences, serving as cognitive shortcuts that streamline judgment and decision-making. These internal models do more than classify objects; they shape expectations, influence behavior, and govern emotional responses across countless daily interactions.

Defined as generalized representations built from salient examples, prototypes emerge early in development through pattern recognition. From infancy, the brain identifies recurring features in people, objects, and situations—recognizing that a four-legged, furry animal with a wagging tail is likely “dog-like” even before formal naming. As cognitive scientist Eleanor Rosch demonstrated in the 1970s, such prototypes are not rigid or perfect, but flexible constructs shaped by cultural context, personal experience, and context-specific information.

“Prototypes are not outlines frozen in stone but dynamic frameworks continuously refined by new data,” notes psychologist Mark Bhelpati. This fluidity enables rapid assimilation of novel stimuli, even when they diverge from typical examples.

How Prototypes Shape Cognitive Efficiency

In an era overwhelmed by information, prototypes function as mental filters that reduce cognitive load.Instead of processing each new experience from scratch, the mind relies on pre-existing templates to assess similarity, predict outcomes, and guide action. For instance, when meeting a new colleague, one unconsciously compares mannerisms, speech patterns, and appearance against internal prototypes—determining whether they fit the “professional norm,” “friendly neighbor,” or “innovative startup founder.” This efficiency comes at a cost, however. Overreliance on prototypes fuels cognitive biases and stereotypes, particularly when prototypes are based on limited or skewed data.

A hiring manager with a prototype linking leadership traits to extroversion, for example, may unconsciously favor candidates fitting that mental model—even if introverted but highly effective leaders exist. As cognitive psychologist Daniel Kahneman observed, “Our minds are efficient, but efficiency often prioritizes speed over accuracy.” Prototypes, while invaluable for conserving mental energy, require conscious calibration to avoid reinforcing rigid worldviews.

The Dual Nature of Prototypes in Social Judgment

Prototypes serve as a double-edged sword in social cognition.On one hand, they foster swift, adaptive responses—enabling individuals to navigate complex social environments without exhaustive analysis. A child learning to identify animals, for instance, quickly classifies a golden retriever as “friendly” based on repeated positive exposure, enabling safe, intuitive interaction. Yet this very mechanism can reinforce harmful assumptions.

When social prototypes draw on cultural stereotypes—such as linking gender and competence or associating age with diminished capability—they entrench bias in everyday judgments. Research by psychologist Jane Thompson reveals that even well-intentioned individuals exhibit faster reaction times when encountering prototype-consistent versus prototype-inconsistent stimuli, a phenomenon known as confirmation bias. “Prototypes act as invisible lenses,” Thompson explains, “shaping perception before conscious processing even begins.” In organizational settings, prototype-driven decisions play out in hiring, performance evaluations, and team dynamics.

A study published in the Journal of Applied Psychology found that managers relying on prototype consistency were 32% less likely to recognize high-potential employees whose profiles deviated from norms. Equally, prototypes can empower positive outcomes—diverse teams with consciously expanded, inclusive prototypes report higher innovation rates and cohesion.

Prototypes Beyond Stereotypes: Expanding Adaptive Flexibility

Despite their limitations, prototypes are not immutable.They evolve through mindful exposure, deliberate uncoupling of behavior from identity, and exposure to diverse examples. Neuroplasticity—the brain’s capacity to rewire based on experience—supports this ongoing refinement. By actively challenging assumptions and engaging with counterexamples, individuals train prototypes to become nuanced and accurate.

Educational and therapeutic interventions exemplify this plasticity. In diversity training programs, exposing participants to counterstereotypical prototype examples reduces bias by prompting mental restructuring. Campers in a U.S.

military leadership program, for instance, showed measurable gains in inclusive decision-making after engaging with stories and role models defying traditional leadership prototypes. In clinical psychology, cognitive-behavioral techniques help clients revise maladaptive prototypes—such as “I am unlovable”—by replacing them with evidence-based alternatives. “Prototypes are not destiny,” emphasizes clinical psychologist Dr.

Lila Chen. “They are assumptions we can consciously inspect, question, and reshape.” This malleability underscores their potential as tools for personal growth and social progress.

Practical Applications and Everyday Impact

Understanding prototype definition psychology empowers individuals across domains to harness mental shortcuts without surrendering critical judgment.In marketing, brands tailor prototypes to align with target values—evoking trust through recognizable symbols while innovating subtly to avoid stagnation. In education, educators leverage prototypes to scaffold learning—using familiar concepts as entry points to complex ideas—while avoiding oversimplification. Medical professionals, too, benefit from

Related Post

Damon Darling Net Worth: A Deep Dive Into the Wealth and Career Trajectory of a Rising Star

Selena Gomez’s Walk of Fame Star Ignites LA’s Glitz and Glad on Her Iconic Ritual Celebration

Florida, Alabama, and Their Shared Geography: A Map-Driven Exploration of the Eastern South’s Crossroads

What Does KKK Mean? The Dark Legacy and Power of a Hate Symbol