Poland’s Transformation: From Communist Shadows to Democratic Crossroads

Poland’s Transformation: From Communist Shadows to Democratic Crossroads

Poland’s story from an oppressive Communist regime to a vibrant modern democracy is one of resilience, upheaval, and ongoing political tension. Decades of Soviet domination left deep societal and institutional imprints, shaping a present where democratic institutions coexist with enduring legacies of control. As Poland journalists, activists, and citizens navigate current challenges—ranging from judicial reforms to debates over historical memory—the country remains caught in a delicate dance between honoring its Communist past and solidifying a democratic present.

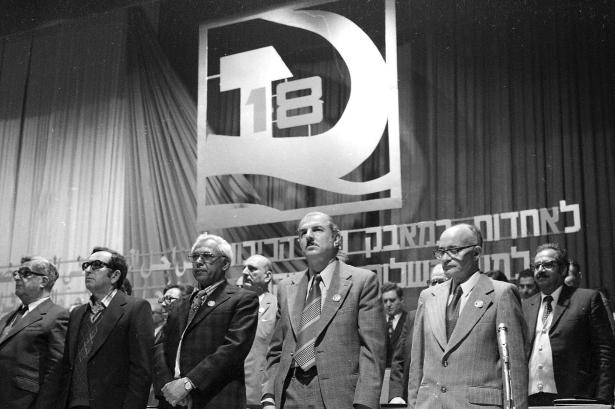

Under Soviet influence from 1945 to 1989, Poland functioned as a satellite state governed by a repressive regime that suppressed dissent, controlled media, and dissolved national autonomy. The Polish United Workers’ Party imposed totalitarian policies, replacing democratic structures with a one-party system rooted in Marxist-Leninist principles. The security apparatus, led by the secret police (UB), monitored citizens through surveillance networks reminiscent of Stalinist purges.

As historian Timothy Snyder noted, Poland under Communism “was not merely ruled by force but saturated with fear”—a state penetration that fractured trust and left generational scars. Resistance persisted despite oppression, most notably through the rising flame of Solidarity. Founded in 1980 at the Gdańsk Shipyard under leader Lech Wałęsa, this trade union evolved into a broad anti-Communist movement, combining workers' rights demands with calls for political freedom.

Solidarity’s symbols—print media distributed underground, clandestine education networks—embodied a quiet revolution that galvanized national identity. By the late 1980s, negotiations between the regime and opposition paved the way for semi-free elections, marking the beginning of the end for Communist rule. The transition to democracy was neither immediate nor un contested.

The Interim Government of National Unity, formed after 1989, faced the Herculean task of dismantling state apparatuses built on repression while establishing democratic institutions. Electoral reforms introduced multi-party politics, but economic restructuring sparked social upheaval. Privatization led to widespread unemployment, and the rapid shift from planned to market economy left many nostalgic for the stability of state-controlled industry—even as activists demanded accountability for past injustices.

One of the most contested legacies of Poland’s Communist era centers on state accountability for historical atrocities. The Ministry of Internal Affairs’ archives, partially released since the 2000s, reveal the scale of surveillance, forced labor camps, and political repression. Yet truth commissions and memorial projects remain incomplete.

As civic groups stress, “Remembering is not just symbolic—it’s a democratic duty,” ensuring citizens are not disenfranchised by historical amnesia or selective memory politicized by current powers.

Political dynamics today reflect a tension between democratic firmness and democratic backsliding. Since 2015, Poland’s Law and Justice (PiS) party has pursued reforms criticized internationally as undermining judicial independence.

The restructuring of courts, public broadcasters, and civil society institutions has raised alarms in Brussels, sparking disputes over rule of law compliance. Supporters of PiS frame reforms as reclaiming sovereignty from EU overreach, while opponents warn of authoritarian drift threatening core democratic values. This polarization echoes earlier Communist-era struggles over state control but occurs within a nominally democratic electoral system—creating friction between populist mandates and institutional checks.

Key social issues further test Poland’s democratic maturation. The 2020 near-total abortion ban, rooted in Catholic tradition but imposed through conservative political coalitions, sparked massive protests and galvanized youth and urban movements advocating reproductive rights. These demonstrations reflect a broader generational shift: while older demographics often align with traditional values, younger Poles increasingly demand liberal freedoms, exposing fault lines within the democratic bloc.

Meanwhile, media freedom remains a battleground—state-controlled outlets purportedly serve partisan agendas, while independent outlets face financial and political pressure—undermining the pluralism essential to democracy.

Memory politics amplify the complexity of Poland’s post-Communist identity. Debates over how to commemorate events like the 1970 protests or the tragedies at Auschwitz’s Auschwitz-Birkenau and Polish-led death camps reveal competing narratives: national martyrdom versus transnational responsibility.

Activists call for inclusive remembrance that confronts both External (Nazi) and Internal (Communist) oppression, but selective commemoration risks reinforcing division rather than unity. As political philosopher Janusz Korczak observed, “A nation’s soul speaks through how it remembers”—and in Poland, that soul remains in negotiation.

Demographic trends also shape Poland’s democratic future.

With one of Europe’s lowest birth rates and significant emigration of young professionals, the country faces long-term socioeconomic strain. These challenges fuel support for strong state intervention—a preference that PiS exploits while critics warn may deepen clientelism and weaken transparent governance. Urban centers, especially Warsaw and Kraków, foster progressive civic engagement and independent media, contrasting with rural regions where Communist-era solidarities and conservative

Related Post

Simoncellis Legacy A Motogp Legend Remembered

Lena Waithe and Cynthia Erivo: A Powerful Bond Forged in Art and Shared Identity

Vika And Vova Jump: The Energizing Force Behind Russia’s Youth Movement

Alina Habba’s Sexy Assertion: Redefining French Femininity Through Confidence and Style