Ochsen: The Powerful Workhorses of Agriculture and Tradition

Ochsen: The Powerful Workhorses of Agriculture and Tradition

Ochsen—derived from the German word for oxen—are not merely large cattle but highly specialized working animals with a profound legacy in human civilization, especially in farming and transportation. Defined as adult male cattle of breeds such as the Echthimer or the prestigious Lincolnshire Ox, oxen represent the pinnacle of strength, endurance, and docility when properly trained. Unlike bulls, which are typically aggressive and used for breeding, oxen are castrated, making them calm, reliable partners in labor.

Their role has evolved over millennia, from ancient plowing in Mesopotamian fields to modern-day draft power in sustainable agriculture. Understanding oxen requires exploring their unique biological traits, historical importance, and how they continue to serve as indispensable assets in rural economies worldwide.

The Biological Profile of Ochsen: Strength and Structure

Ochsen possess a distinctive physiology that aligns perfectly with their role as draft animals.With mature weights ranging from 1,200 to over 2,000 kilograms depending on breed and care, they are among the heaviest Domesticated cattle. Their massive musculature—especially developed in the neck, shoulders, and rear—enables sustained pulling power essential for plowing, carting, and other labor-intensive tasks. Unlike their more agile female counterparts (cows), castrated males exhibit reduced aggression, increased patience, and greater consistency, making them ideal for repetitive, high-demand work.

Standing between 1.5 to 1.8 meters at the shoulder, oxen combine substantial height and girth without sacrificing agility on uneven terrain. Their deep chest width supports powerful respiratory and cardiovascular systems, enabling efficient oxygen use during prolonged exertion. Equine-like stamina and calm temperament allow oxen to work safely in sync with human operators, minimizing risks in field conditions.

“These animals are living engines—flawless in endurance, predictable in temperament, and indomitable in spirit,” notes agricultural historian Dr. Anja Weber, emphasizing their specialized adaptation to farm labor.

- Physical Attributes: Average mature weight: 1,200–2,000 kg; height: 1.5–1.8 m; deep musculature in shoulders and back.

- Domesticated Stock: Common breeds include the Echthimer (Europe), Zebu derivatives with humped frames in warmer climates, and the Lincolnshire Ox (notable for lean muscle and draft efficiency).

- Behavioral Traits: Calm disposition due to castration; high trainability with consistent handling; exceptional social cohesion within herds.

- Metabolic Efficiency: Adapted to low-energy, high-duration tasks—optimal for sustained pulling without rapid fatigue.

Historical Significance: From Plow to Progress

> Oxen have been central to agricultural advancement since the dawn of settled farming.Archaeological evidence traces oxen domestication to the Fertile Crescent over 6,000 years ago, where their draft capability revolutionized irrigation and soil cultivation. In ancient Egypt, oxen pulled plows powered by hand-frames, accelerating grain production and enabling complex societal development. Similarly, in the Indus Valley and later in Roman and medieval European farms, oxen were the backbone of rural economies—plowing fields, hauling lumber, and transporting grain across vast networks.

> “Oxen weren’t just tools; they were partners in transformation,” says David Carter, professor of historical agronomy at the University of Göttingen. “Their consistent labor allowed civilizations to expand beyond subsistence farming into surplus-based trade and urbanization.” Their use persisted through the Industrial Revolution not as obsolete laborers, but as reliable alternatives to early mechanical engines—especially in regions where steam power was impractical. Even today, in remote mountainous areas of the Himalayas, Andean highlands, and sub-Saharan Africa, oxen remain vital for terrace farming and smallholder cultivation.

- Ancient Foundations: Domestication began ~6,000 years ago, enabling early surplus farming and societal complexity.

- Global Diffusion: Widespread adoption in Mesopotamia, South Asia, and Europe as core agricultural engines.

- Resilience in Modern Farming:

- Used in low-input, sustainable systems where fuel and machinery are scarce.

- Ideal for rotational grazing and delicate soil management.

- Cultural Legacy:

- Symbolic in mythology and folklore as enduring, faithful laborers.

- Staple in festivals, rural processions, and traditional celebrations.

Modern Roles: Oxen in Sustainable and Smart Agriculture

> Within contemporary farming landscapes, oxen have found renewed value in sustainable agriculture and agroecology. As concerns over energy use, carbon emissions, and synthetic inputs grow, many small-scale and organic producers turn to oxen-based systems. Their low fuel dependency and minimal environmental footprint align with regenerative farming principles, reducing reliance on fossil-powered machinery while maintaining productivity.Oxen face fewer limitations than horses or mules in rugged terrain, offering superior traction on uneven soil without causing compaction. “When paired with pasture rotation and rotational grazing, oxen help restore soil microbiology and carbon sequestration,” explains Maria Lang, director of eco

Related Post

July 5’s Cancer: Unveiling the Deeply Emotional and Loyal Zodiac Sign

What Is April 24 Zodiac Sign Discover The Traits And Characteristics

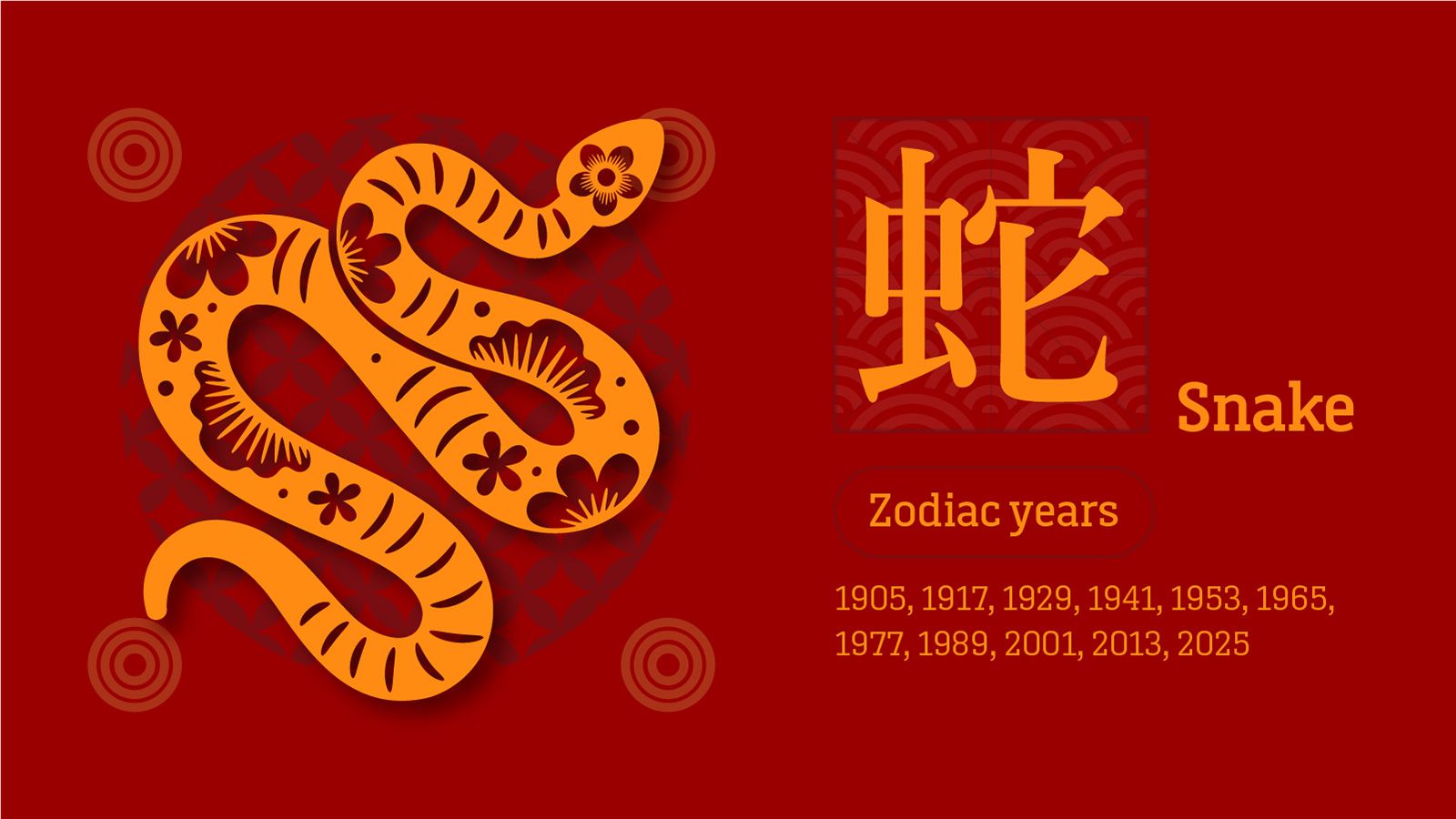

Born 1965 in the Year of the Snake? Unlock Your Chinese Zodiac Personality — Practical Wisdom Meets Deep Intuition

The Ideological Blueprint: Decoding Typical Political Party Affiliation Patterns