Oceanic-Continental Convergent Boundaries: Where Subduction Fuels Earth’s Most Intense Geological Drama

Oceanic-Continental Convergent Boundaries: Where Subduction Fuels Earth’s Most Intense Geological Drama

Beneath the vast blue spans of the Pacific Ocean, a profound geological dance unfolds at oceanic-continental convergent boundaries—regions where tectonic plates collide with breathtaking violence and complexity. These boundaries, defined by the relentless descent of dense oceanic crust beneath lighter continental plates, drive some of Earth’s most catastrophic earthquakes, explosive volcanoes, and dramatic mountain-building events. The process, marked by subduction, reshapes continents, alters landscapes, and endangers millions living along vulnerable coastlines.

From the jagged peaks of the Andes to the fiery rims of Japan’s archipelago, these zones exemplify nature’s raw power—silent beneath the waves, yet deafening in consequence.

The Mechanics of Subduction: How Oceanic Meets Continental

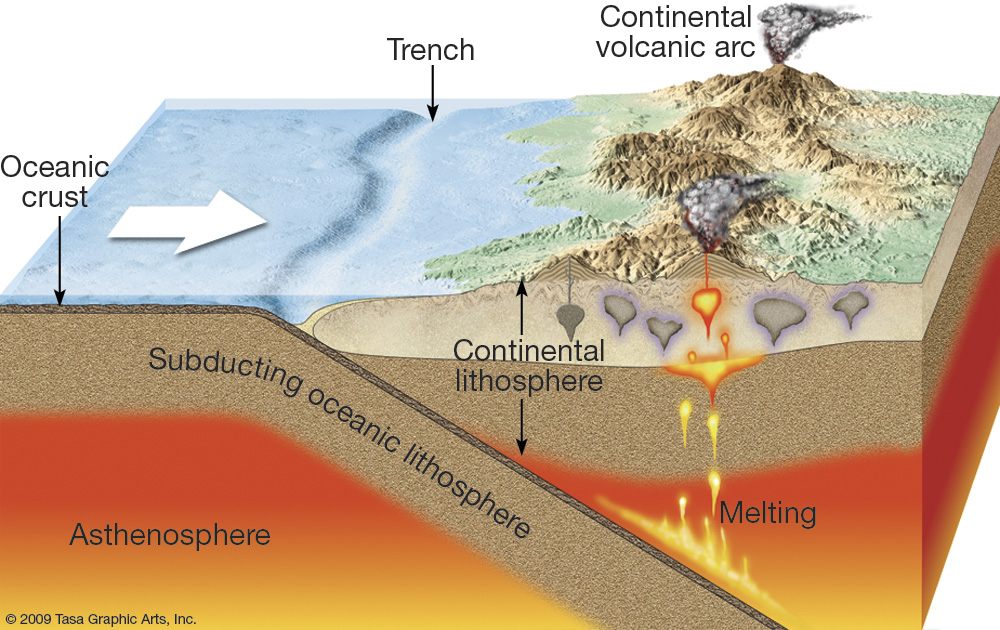

At oceanic-continental convergent boundaries, the denser oceanic plate is forced beneath the less dense continental lithosphere in a process known as subduction. This relentless downward plunge, occurring at rates between 2 to 10 centimeters per year, initiates a cascade of geological phenomena.As the oceanic slab sinks into the mantle—often reaching depths exceeding 700 kilometers—it undergoes intense pressure and temperature increases. This triggers dehydration reactions, releasing water that lowers the melting point of the overlying mantle wedge, generating magma that fuels volcanic arcs.

- The incoming oceanic plate carries hydrated minerals; as it descends, these minerals break down due to rising heat, releasing water into the mantle beneath.

- This water induces partial melting in the asthenosphere, generating magma rich in silica and volatile gases.

- Over millions of years, repeated magma intrusion builds volcanic centers, forming mountain chains that rise dramatically above sea level.

- Meanwhile, the continental margin experiences intense compressional stress, leading to crustal thickening, folding, and uplift.

“The descent of oceanic crust isn’t just passive slipping—it’s the engine behind volcanic mountain-building and the currency of continental growth,” notes Dr. Elena Marquez, a volcanologist at the University of Chile.

Earthquakes Beneath the Surface: Power Beneath the Tectonic Scream

One of the most immediate and dangerous effects of oceanic-continental convergence is seismic activity.The friction between descending and overriding plates locks the interface, causing stress to accumulate over centuries. When this stress finally ruptures, it releases energy equivalent to massive earthquakes. Subduction zones host some of the planet’s most powerful quakes—events that can exceed magnitude 9.0.

The mechanics of these quakes depend on the specific geometry and age of the subducting slab. Younger, warmer oceanic plates subduct more shallowly and may generate shallow thrust faults capable of producing tsunamis. Older, colder slabs plunge deeper and aid intraslab earthquakes at greater depths.

The 2011 Tōhoku earthquake in Japan—a 9.0-magnitude megathrust rupture—epitomizes this threat, triggering a devastating tsunami that reshaped coastlines and redefined disaster preparedness. Key facts on seismic hazards:

- Subduction zones account for approximately 90% of the world’s largest earthquakes.

- Interplate thrust quakes dominate at shallow depths, often near coasts.

- Intraslab events occur deeper within the subducting plate, posing hidden risks to inland regions.

- Earthquake recurrence intervals vary from decades to millennia, depending on convergence rates and fault locking patterns.

Volcanic Fire: The Birth of New Land and Destruction in Equal Measure

As the oceanic slab descends, water released into the mantle lowers the melting temperature, sparking magma generation. This magma ascends through the continental crust, feeding volcanic arcs that dramatic rise from the seafloor into the sky—landforms carved by fire and time. The resulting volcanoes are not just geological wonders but active threats, capable of catastrophic eruptions that blanketed regions in ash and pyroclastic flows.The Cascade Range in the northwestern United States—formed by the Juan de Fuca Plate subducting beneath North America—includes iconic volcanoes like Mount St. Helens and Mount Rainier. Historical eruptions, such as the 1980 Mount St.

Helens blast, devastated ecosystems and underscored the volatile nature of these zones. “Volcanoes at subduction boundaries are time capsules—releasing deep Earth materials and volatile elements, sealing cycles of crustal recycling,” explains Dr. Kenji Tanaka of the Smithsonian Institution.

Volcanic hazards include lava flows, lahars (destructive mudflows), ash fallout disrupting air travel, and toxic gas emissions. Monitoring networks, utilizing satellite imagery, gas sensors, and seismographs, strive to provide warning before eruptions, though unpredictable behavior remains a challenge.

Shaping Continents and Coastal Futures: Long-Term Geological Legacy

Beyond immediate hazards, oceanic-continental convergence drives profound, lasting changes to Earth’s surface.The accumulation of volcanic material and tectonic uplift slowly builds continental margins layer upon layer, expanding landmasses over geologic time. Sediments eroded from rising mountains accumulate in adjacent forearc basins, creating fertile deltaic plains and complex sedimentary records that scientists study to reconstruct past climates and tectonic shifts. In Japan, where the Pacific Plate subducts beneath the Eurasian Plate, the interplay between uplift and

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Continental-continental_destructive_plate_boundary_LABELED-56c55a0e3df78c763fa34493.png)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Oceanic-continental_destructive_plate_boundary_LABELED1-56c559c43df78c763fa341bf.png)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/b8f413db-8bdd-44b8-a0c2-9cc209028ede-56c559863df78c763fa33ff9.png)

Related Post

Subhashree Sahu Season 3 MMS Controversy: How A Compromised Film Moment Sparked A Media Storm

Nestle Douglas Stress B Plus Recall Sparks Consumer Concern Over Contamination Risk

The Power of Data: Linda Chattin’s Statistics Videos Redefine How We Learn Numbers

Fast Food in Crossville, TN: Where Roadside Hunger Meets Culinary Convenience