Nigeria’s First-Order Caps: The Strategic Geography of State Capitals

Nigeria’s First-Order Caps: The Strategic Geography of State Capitals

Nigeria’s 36 state capitals form more than just administrative centers—they are vital nodes in the country’s political, cultural, and economic fabric. Each capital serves as the nerve center for governance, development, and identity within its region, reflecting Nigeria’s complex ethnic, historical, and spatial dynamics. From coastal ports to inland hubs, these seats of power influence everything from electoral outcomes to infrastructure investment, shaping national cohesion and regional development.

Understanding their placement and function reveals deeper insights into Nigeria’s unity and diversity.

Defining the Capitals: A Brief Overview

Nigeria officially recognizes 36 state capitals—one per state—established primarily during post-independence administrative reforms. While Lagos remains the former capital and major commercial hub, each state capital functions as the seat of local government, housing key civic institutions such as district courts, state ministries, and parliamentary chambers.These capitals vary dramatically in size, infrastructure, and economic activity. Abidevbo, the capital of Ondo State, contrasts sharply with Minna, the administrative center of Niger State, illustrating how geography and development priorities shape regional capitals. The selection of capitals often reflects historical, economic, and demographic considerations.

For example, Soutele—a planned capital under earlier federal design—was never realized, underscoring the organic, often politically driven evolution of Nigeria’s administrative geography. Instead, capitals like Abuja (the national capital), Benin City (Benue State), and Lafia (L profonda State) evolved from existing urban centers chosen for accessibility, centrality, and symbolic relevance within their respective regions.

The Historical Evolution of State Capitals

Prior to Nigeria’s independence, colonial administers governed from scattered outposts such as Lagos, Port Harcourt, and Kaduna.Post-1960, the need for a decentralized governance model prompted the creation of state-level administrative centers. This shift aimed to reduce chronic regional imbalances and foster equitable development. The 1976 creation of the 12 states, followed by expansions to 36, cemented capitals as critical anchors for state authority.

Historical patronage played a decisive role: capital designations often honored influential traditional rulers, nationalist figures, or symbolic geographic landmarks. For instance, Okene in Kogi State was chosen in part due to its historical significance in Nigeria’s precolonial trade routes. Such decisions embedded cultural memory into administrative planning, ensuring capitals resonate with both historical depth and contemporary relevance.

Geographic Distribution and Regional Balance

Nigeria’s state capitals are intentionally spread across all six geopolitical zones—North-West, North-East, South-South, South-East, South-South, and Middle Belt—reflecting an effort toward equitable federal representation. This geographic dispersal prevents concentration of power and supports balanced national development. - **South-South** houses key capitals like Benin City and Calabar, serving as economic and cultural gateways with rich oil histories and vibrant tourism.- **South-East** features Owerri and Umuahia, centers of Igbo heritage and growing industrial corridors. - **Middle Belt** features capitals such as Jos (Plateau) and Makurdi (Benue), critical for bridging North-South divides and managing agrarian and pastoralist tensions. - **North-West**’s capital, Sokoto, and **North-East**’s Maiduguri reflect post-insurgency revitalization priorities, demonstrating capitals as instruments of recovery.

- **Central**’s Abuja—though not a state capital—acts as Nigeria’s adjacent federal capital, influencing all state capitals via national policy flow. This intentional zonal distribution underscores a federal commitment to preventing regional marginalization, with each capital acting as a symbol and engine of local empowerment.

Capital Cities and Political Significance

State capitals are not merely administrative offices; they are political powerhubs influencing election dynamics, policy implementation, and intergovernmental relations.Their centrality enhances visibility for regional representatives, amplifying their role in national discourse. For instance, Abuja (as national capital) exerts gravitational pull over all states, but state capitals maintain critical autonomy. In Rivers State, the capital Asaba functions as the nerve center of oil-rich governance, while Plateau State’s Jos balances mineral wealth with security challenges.

Capitals often host electoral campaigns, state legislative sessions, and donor coordination forums, solidifying their status as political battlegrounds and decision-making epicenters. Moreover, capitals drive inclusivity by decentralizing government functions. In Ol調査显示 (Niger State), the capital Minna houses the State Emergency Management Agency, ensuring rapid response to floods and banditry—threats that disproportionately affect rural zones.

This operational proximity strengthens accountability and service delivery, reinforcing capitals as vital for state resilience.

Economic and Social Impact of Capitals

Beyond politics, state capitals function as economic engines fueling regional growth. Their markets, industrial zones, and service hubs attract investment, labor, and infrastructure, triggering cascading development across surrounding areas.Take Kaduna, a central North-West capital. Once a military stronghold, Kaduna has evolved into a commercial nexus linking northern farmers to southern ports. Its industrial park supports thousands, drawing entrepreneurs and migrants alike.

Similarly, the capital of Delta State, Asaba, leverages its riverine location for trade and logistics, boosting agricultural exports. Socially, capitals serve as centers of education, healthcare, and culture. Benin City, though under pressure from rapid urbanization, hosts renowned institutions like the University of Benin and the Benin City Museum, preserving Edo heritage while nurturing human capital.

In contrast, smaller capitals such as Malam-Ya’u in Nasarawa State offer blossoming municipal services and community centers that strengthen grassroots development. Capital cities also serve as cultural crossroads. Calabar, for example, hosts the annual Calabar Carnival—Nigeria’s largest street festival—drawing millions and reinforcing identity beyond political boundaries.

These cultural interactions foster unity amid Niger’s complex ethnic mosaic.

Challenges Facing State Capitals

Despite their importance, Nigerian state capitals confront systemic challenges that threaten their functionality and equity. Rapid urbanization often outpaces infrastructure development.Traffic congestion in Benin and traffic gridlock in Makurdi disrupts governance and economic activity. Inadequate sanitation, power shortages, and informal settlements strain public services, especially in growing cities like Lavun (Katsina State) and Lel tile (Adamawa). Security remains a persistent concern.

In the Middle Belt, capitals such as Jos and Mkwarteng navigate intercommunal tensions between farmers and herders, requiring robust security coordination. Meanwhile, coastal capitals like Lagos—though limited in state status but influential—face flooding and environmental degradation due to climate change, privatizing development risks. Fiscal constraints further limit expansion potential.

Many capitals rely on uneven federal appropriations, hindering long-term planning. However, innovative local initiatives, such as Edo State’s capitalOur_Server—autonomous urban renewal—offer promising models for resilient capital development.

Planning the Future: Balancing Tradition and Innovation

Looking forward, Nigeria’s state capitals must adapt to demographic surge, climate pressures, and digital transformation.Smart city concepts—integrating GIS mapping, renewable energy, and public transit—are emerging in master plans for Abuja’s environs and nascent capitals in newly created states like Gombe’s adjacent zones. The Federal Capital Territory and the ongoing federal capital development reinforce the need for harmonized planning. State capitals stand to benefit from inclusive zoning, expanded public transport, and green infrastructure, ensuring sustainability amplifies their role as engines of growth.

Furthermore, enhancing digital governance—through e-courts, online permits, and telemedicine—can reduce urban congestion and improve access across regions. Given the rising reach of rural populations, mobile government units in secondary towns may redefine the traditional capitals’ monopoly on service delivery, extending equity to the periphery. capitals thus emerge not static nodes, but dynamic, evolving centers of innovation, inclusion, and identity—reflecting Nigeria’s enduring quest to unify its vast space through intelligent, responsive administration.

States capitals in Nigeria are far more than administrative offices; they are living embodiments of governance, culture, and development. From port cities to interior hubs, each capital shapes and is shaped by the communities it serves, standing at the crossroads of history and progress. Their strategic placement, political weight, and social influence underpin Nigeria’s federal promise—offering not just locations on a map, but pathways toward a more cohesive, vibrant nation.

Related Post

Top Ukraine Military Telegram Channels: The Frontlines Speak High Through Encrypted Chatter

Bulls Vs Celtics: The Unforgettable Clash That Defines an Era

Unlock the Unbreakable Mystery of DriftBossGlitches: The Hidden Glitches Shaping Competitive Driftening

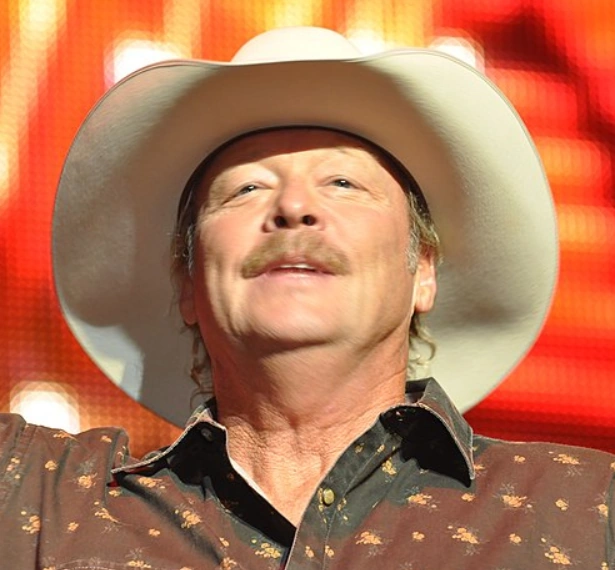

Alan Jackson Christian Music: A Quiet Revolution in Faith-Driven Soulful Storytelling