Monomers: The Foundation of Carbohydrate Science – Building Blocks That Shape Life

Monomers: The Foundation of Carbohydrate Science – Building Blocks That Shape Life

Carbohydrates, fundamental to biology and human nutrition, owe their structure and function to modular monomers—simple molecular units that polymerize into complex polymers. These building blocks, primarily monosaccharides, serve as the essential foundation for all carbohydrate molecules, driving processes as vital as energy storage, cellular communication, and structural support. Understanding their chemistry reveals not just biological mechanisms but also innovations in medicine, food science, and materials engineering.

The monomeric core of carbohydrates is both a testament to nature’s precision and a gateway to human ingenuity.

The Core Monomer: Monosaccharides as Structural Units

At the heart of every carbohydrate lies the monosaccharide—a single sugar molecule, often composed of five to seven carbon atoms. These short-chain molecules, derived from fundamental carbon-hydrogen-oxygen building blocks, assemble into longer chains via glycosidic linkages, forming oligosaccharides and polysaccharides. The versatility of monosaccharides arises from their versatile functional groups, particularly the carbonyl (aldehyde or ketone) and hydroxyl groups, which dictate reactivity and polymerization pathways.

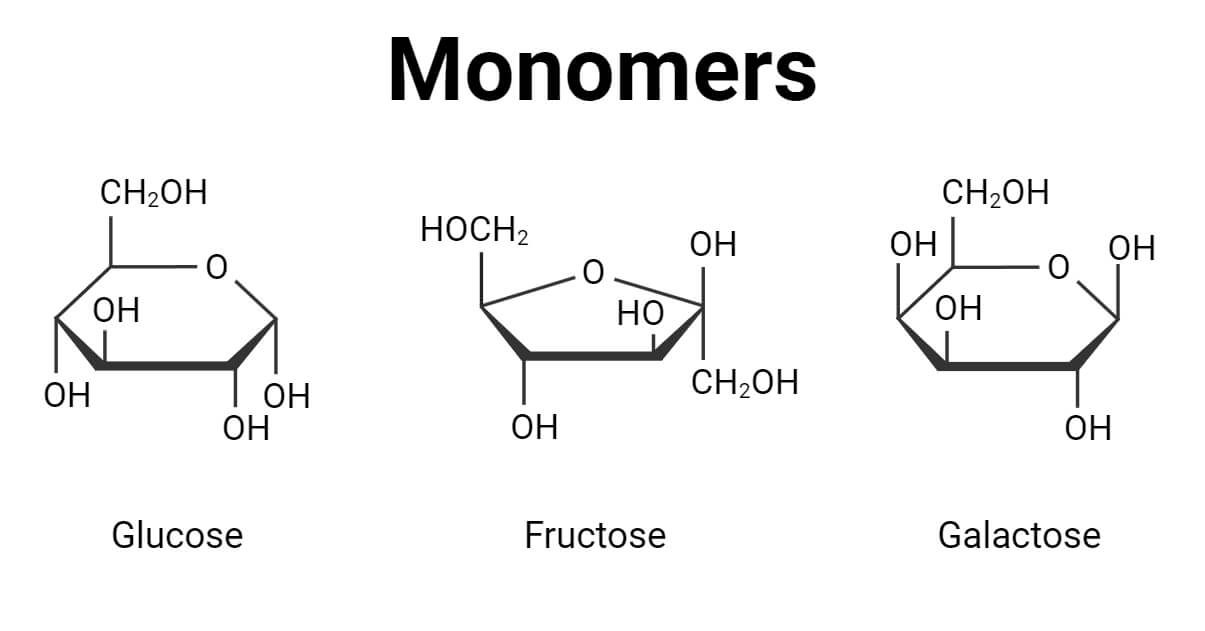

Typically, monosaccharides contain the general formula (CH₂O)ₙ, where n ranges from three (trioses) to seven or more (hexoses, heptoses). The most biologically significant monosaccharides include glucose, fructose, and galactose—hexoses that fuel cellular metabolism, alongside fructose, the primary sugar in fruit and sucrose. Each monosaccharide exhibits a unique spatial configuration around its chiral centers, influencing how it binds with other units.

“The chirality and spatial arrangement of monosaccharides are critical,” notes Dr. Elena Thompson, a carbohydrate biochemist at MIT. “These subtle differences determine whether the resulting polymer is starch, cellulose, or chitin—each serving distinct biological roles.”

The Role of Carbon as the Central Architect

Carbon’s unique tetravalency enables monosaccharides to form complex, stable structures through ring formation.

In solution, monosaccharides cyclize to generate pyranose or furanose rings—five- or six-membered rings that dictate metabolic pathways. For example, glucose predominantly exists as α- or β-D-glucose in the pyranose form, a conformation essential for enzymatic recognition. This carbon-centric architecture provides the scaffold for diversity: hydrogen bonding, ring flexibility, and substitution patterns allow monosaccharides to support a staggering array of carbohydrate functions.

The variability in hydroxyl group placement—ronearly ten per monosaccharide—creates opportunities for differential reactivity. These groups serve as attachment points for glycosidic bonds, enabling monosaccharides to link in diverse orientations, thus forming linear chains or branched architectures critical for structural integrity and biological signaling.

Building Longer Chains: From Monomers to Complex Polymers

Once polymerized, monosaccharides form polysaccharides with specialized roles—starch for energy storage, cellulose for plant cell walls, and glycogen for animal glycogen reserves.

The process begins with glycosidic linkages, covalent bonds formed between the anomeric carbon of one monomer and a hydroxyl group of another. The nature of these linkages—α or β, and their bond geometry—dictates polymer properties and biological function. For instance, glucose units in starch link via α(1→4) glycosidic bonds in amylose, creating helical structures that efficiently store energy.

In contrast, β(1→4) linkages in cellulose produce rigid, linear chains that resist digestion, forming the structural backbone of plant cell walls. This precision in monomer connectivity exemplifies how building blocks become functional macromolecules through controlled molecular assembly.

Beyond Fuel: Functional Diversity of Carbohydrate Building Blocks

While glucose and its derivatives dominate energy metabolism, monosaccharide derivatives expand carbohydrate versatility.

Fructose, a ketose monosaccharide, contributes sweetness and plays a key role in fructose metabolism. Galactose, an epimer of glucose, supports lactose formation in milk and participates in lysosomal glycosylation. Meanwhile, sugar alcohols like sorbitol and xylitol—modified monosaccharide derivatives—appear in pharmaceuticals and sugar-free products, offering bulk without glycemic impact.

“Monomers are not just precursors; they are functional molecules that enable structural, metabolic, and signaling roles,” explains Dr. Raj Patel, a carbohydrate chemist at Stanford University. “Their modular design allows enzymes to tailor polymers with exquisite specificity, driving evolution’s ingenuity and inspiring synthetic applications.”

Engineering Carbohydrates: Biotechnology and Innovation

Modern biotechnology leverages monomeric principles to design novel carbohydrates for medicine, materials, and sustainability.

Synthetic glycosaminoglycans mimic natural extracellular matrix components, aiding regenerative therapies. Engineered polysaccharides serve as biodegradable plastics and drug delivery vectors, capitalizing on sugar-based polymers’ environmental compatibility and biocompatibility. Recent advances include glycan arrays—high-density monosaccharide patterns used to map immune interactions—and enzymatic synthesis techniques that allow precise monomer linkage.

“The monomer remains a frontier for innovation,” remarks Dr. Mehreen Ali, a biomaterials scientist at Harvard. “By understanding and redirecting its building-block logic, we unlock new ways to address challenges in health, food security, and environmental preservation.”

The Monomer Legacy: Carbon’s Enduring Impact on Life and Industry

The journey from simple monosaccharide monomers to complex carbohydrate architectures illustrates a fundamental biological theme—function derived from molecular specificity.

Carbon’s role in forming diverse, stable sugar rings and enabling precise glycosidic connections underpins the structural and functional plasticity of carbohydrates. These building blocks not only sustain life but increasingly empower scientific advancement, driving breakthroughs in medicine, materials, and green technology. The monomer is more than a chemical unit; it is nature’s elegant unit of complexity, a dynamic platform where chemistry meets function.

As researchers delve deeper into carbohydrate science, the monomeric foundation continues to illuminate pathways toward a more sustainable and health-conscious future.

.PNG)

Related Post

The Simple Force that Transforms Investing: The Little Book of Common Sense Investing Explained

Twitter’s Charlie Kirk Turns Conservative Message into Viral Movement

MSc Education: Digital & Social Change At Oxford—Redefining Learning for a Connected World

2025: Inteligência Suprema – Trailer Breakdown! The AI That Redefines Superintelligence