Molecular Geometry: Decoding How Atoms Arrange Themselves in Space

Molecular Geometry: Decoding How Atoms Arrange Themselves in Space

The spatial arrangement of atoms within a molecule—known as molecular geometry—is far more than a static abstract concept; it is the silent architect behind chemical reactivity, physical properties, and biological function. At the heart of this discipline lies VSEPR theory and bent environments, which together provide a rigorous framework for predicting molecular shape from electron domain interactions. Understanding how lone pairs distort ideal symmetry, and how atoms align in three-dimensional space, enables scientists to anticipate everything from vapor pressure to enzyme-substrate binding.

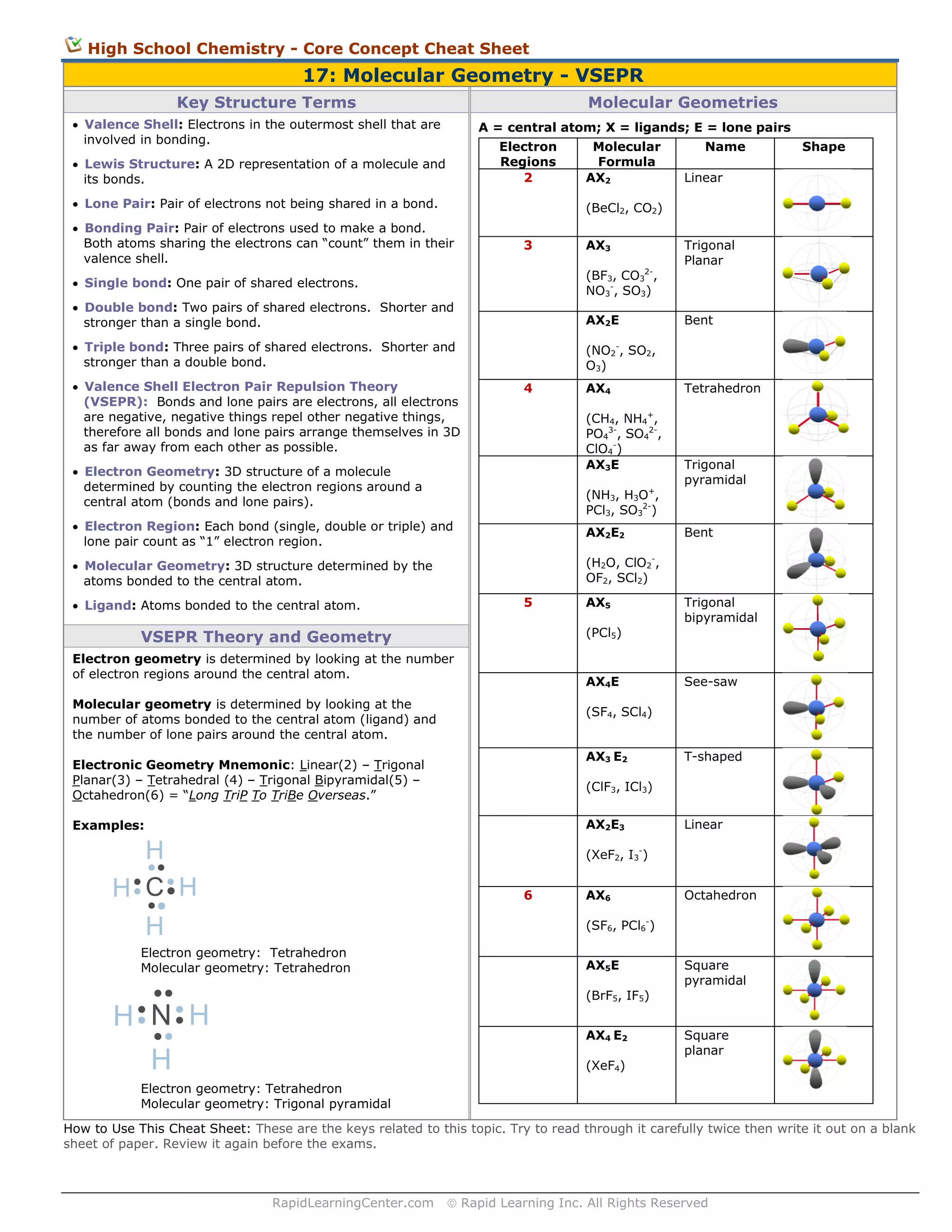

More than just a visualization tool, molecular geometry is essential to modern chemistry, pharmaceutical development, and materials science. Underlying Principles: VSEPR Theory and Electron Domain Repulsion At the core of molecular geometry is VSEPR theory—valence shell electron pair repulsion—which posits that electron pairs around a central atom arrange themselves spatially to minimize repulsive forces. Each bonding pair and lone pair occupies space and pushes adjacent domains away to reduce inter-electron repulsion.

The resulting geometry depends not only on the number of electron groups but also on their dispersion—whether they are single bonds, double bonds, or lone pairs. For example, while carbon dioxide (CO₂) adopts a linear geometry due to two electron domains with no lone pairs, water (H₂O) deviates significantly because two of its four electron domains are lone pairs, creating a bent shape. VSEPR’s predictive power rests on geometry patterns like trigonal planar, tetrahedral, and linear—each corresponding to specific electron domain counts.

But with lone pairs in the mix, ideal symmetry breaks. A molecule like ammonia (NH₃) begins with a tetrahedral electron domain arrangement around nitrogen, but the lone pair compresses the bonding angles from the ideal 109.5° to 107°, producing a trigonal pyramidal molecular geometry. This distortion directly impacts polarity and reactivity, demonstrating how geometry governs function.

The Bent Geometry: Where Symmetry Breaks to Define Function Bent molecular geometry emerges when a central atom is bonded to two or three atoms with one or more lone pairs, distorting expected symmetry. This geometry is most familiarly exemplified by water—H₂O—but also appears in molecules like ozone (O₃), where resonance and lone pair repulsion produce a bent structure critical to its role as a greenhouse gas and oxidizing agent. Bent molecules share key features: bond angles compressed below ideal values, asymmetric charge distribution, and enhanced intermolecular interactions due to asymmetry.

In ozone, the bent shape enables resonance stabilization between two equivalent O–O–O angles near 117°, balancing charge and enhancing reactivity. In atmospheric chemistry, bent geometries often correlate with higher polarity and stronger hydrogen bonding—properties that govern phase behavior and environmental persistence. Practical Implications: From Drugs to Disaster Molecular geometry’s real-world impact spans multiple scientific domains.

In pharmaceutical design, the precise 3D shape of a drug molecule determines how it binds to protein targets. A single atom’s repositioning—such as changing bond angles—can shift binding affinity from ineffective to life-saving. Take oseltamivir (Tamiflu), an antiviral whose carboxylate and dihydropyran rings must align correctly within the neuraminidase enzyme’s active site to inhibit viral release.

Beyond medicine, molecular geometry influences materials. The bent shape of silicate tetrahedra, for

Related Post

What Time Is It in Taiwan? The Global Clock Where Two Worlds Meet

Discover the Taste of Innovation: How LivingstonDiningHall Menu Redefines Campus Dining

Steve Burns’ Wife: Behind the Scenes of a Tech Visionary’s Personal Life

The School of The New York Times: Is the Investment Worth the Future?