Linkage and Linkage Disequilibrium: The Hidden Threads Shaping Genetic Inheritance

Linkage and Linkage Disequilibrium: The Hidden Threads Shaping Genetic Inheritance

When studying how genes are inherited and distributed across populations, two foundational genomic concepts—linkage and linkage disequilibrium—reveal profound insights into evolutionary forces, disease susceptibility, and the architecture of genetic variation. Far more than abstract principles, these mechanisms illuminate the intricate web of inheritance, where nearby genes often ride the same evolutionary current, and deviations from expected allele patterns expose the fingerprints of selection, migration, and genetic drift.

At the heart of genetic mapping lies linkage—the physical proximity of genes on a chromosome that tends to cause their Allele combinations to be inherited together more frequently than chance would predict.

This phenomenon, first observed in Mendel’s followers and later quantified through intense linkage studies, stems from the limited recombination during meiosis. When genes reside close within a chromosomal segment, they resist the shuffling effect of crossover events, preserving specific allele combinations across generations.

Still, linkage alone does not define genetic patterns across populations. Linkage disequilibrium—often abbreviated LD—providerly reveals a deeper story: the non-random association of alleles at different loci, even when physical distance between genes is considerable.Unlike linkage, which focuses on covariation within a single meiotic event, LD captures the cumulative history of populations: how time, selection, and demographic shifts have shaped allele frequencies. “Linkage disequilibrium preserves a snapshot of evolutionary processes,” explains geneticist Sarah Chen. “It’s the memory of how alleles have been inherited, spaced apart or kept close through generations under natural selection or population bottlenecks.”

Quantifying LD requires careful statistical modeling, often expressed via D’ and r² values, which measure the degree of association between specific genotype combinations relative to expectations under random mating.

The magnitude and decay of LD vary dramatically across genomic regions, influenced by recombination hotspots, mutation rates, and local selection pressures. In regions with high genetic diversity, LD tends to be transient, eroded by frequent recombination events over many generations. Conversely, in isolated or recently changed populations—such as those affected by founder effects—LD persists over larger chromosomal spans, creating extended blocks of correlated alleles.

Mechanisms Driving LD Patterns LD arises through several interlocking mechanisms: - Genetic Recombination: The primary force counteracting linkage—intermediate crossover frequencies break apart allele associations over time.Recombination rates are not uniform; regions near centromeres or with recombination suppression exhibit extended LD, making them ideal for fine-mapping disease loci. - Population Structure: Subdivided groups with limited gene flow preserve unique allele combinations, increasing local LD. For example, indigenous populations with long-term isolation often display higher LD, simplifying GWAS (Genome-Wide Association Studies) in these cohorts.

- Natural Selection: Selective sweeps dramatically amplify LD. When a beneficial allele rises rapidly in frequency, linked neutral variants “ride along,” inflating association signals detectable across chromosomes—evidence of recent adaptive evolution. Conversely, purifying selection removes deleterious allele combinations, reducing LD in functional regions.

- Demographic History: Founder effects, bottlenecks, and migrations redistribute genetic variation. Small founding populations or recent admixture events generate long-range LD spikes, layers of genetic history embedded in modern genomes.

Understanding LD is indispensable in modern genomics.

In medical genetics, LD enables biologically cost-effective GWAS, where genotypes at sampled SNPs indirectly infer associations for untyped variants. “LD bridges the gap between genetic markers and causal function,” says bioinformatician James Okoye. “Without accurate LD maps, pinpointing disease-causing mutations would be like searching for a needle in a shifting haystack.” In cancer genomics, LD patterns help distinguish germline drivers from somatic events by tracing shared allele histories.

Similarly, evolutionary biologists exploit LD to reconstruct ancient population migrations, detect archaic introgression, and infer selection signatures in genes linked to immunity, metabolism, and cognition.

Challenges persist, however. LD varies across ethnic groups due to differing demographic histories, emphasizing the need for diverse genomic databases.

Biased reference panels can diminish LD accuracy in underrepresented populations, risking disparities in precision medicine. Moreover, distinguishing true biological LD from spurious correlations in high-dimensional data requires robust statistical frameworks and wary interpretation.

What emerges is a nuanced portrait of inheritance—not as a linear transmission of discrete genes, but as a dynamic, interconnected mosaic shaped by billions of years of molecular evolution.

Linkage and linkage disequilibrium are not merely technical concepts but conceptual lenses through which we decode the genetic blueprint of life itself. As sequencing technologies grow more pervasive and analytical methods more refined, the silent language of LD continues to speak volumes—revealing hidden genetic narratives long encoded in the architecture of chromosomes.

The Evolutionary Pulse of LD in Human Populations

In specific cases, LD offers a temporal window into human history.For instance, populations with recent African origins still show extended LD blocks, a signature of rapid expansion and limited recombination in early settlers. In contrast, long-isolated populations like the Finnish mitigate recombination over time, generating LD that preserves disease-associated haplotypes, facilitating gene discovery for rare disorders. “Every genome carries a family tree,” notes population geneticist Alina Petrova.

“LD turns millions of SNPs into a chronicle of ancestry, adaptation, and survival.” Moreover, linkage disequilibrium is instrumental in pharmacogenomics, where allele combinations influence drug response. Knowing LD in key metabolic enzyme loci allows clinicians to predict individual risk of adverse reactions, personalizing treatments with precision once thought impossible.

Bridging Theory and Application

From fine-mapping disease genes to tracing human migrations, linkage and LD remain cornerstones of genomic inquiry.While statistical models grow more sophisticated, the core principles endure: proximity preserves association, and patterns betray history. As research expands into more diverse populations and complex disease architectures, the interplay between genetic linkage and disequilibrium will continue to deliver transformative revelations. Far from mere footnotes in textbooks, they shape the frontiers of medicine, evolution, and human identity—anchoring genetic science in tangible, human terms.

Related Post

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(999x0:1001x2)/david-burtka-harper-grace-neil-patrick-harris-gideon-091123-781feb01282741038c4f303ae339a5c2.jpg)

David Burtka: From Sitcom Star to Studio Powerhouse and Gaming Icon

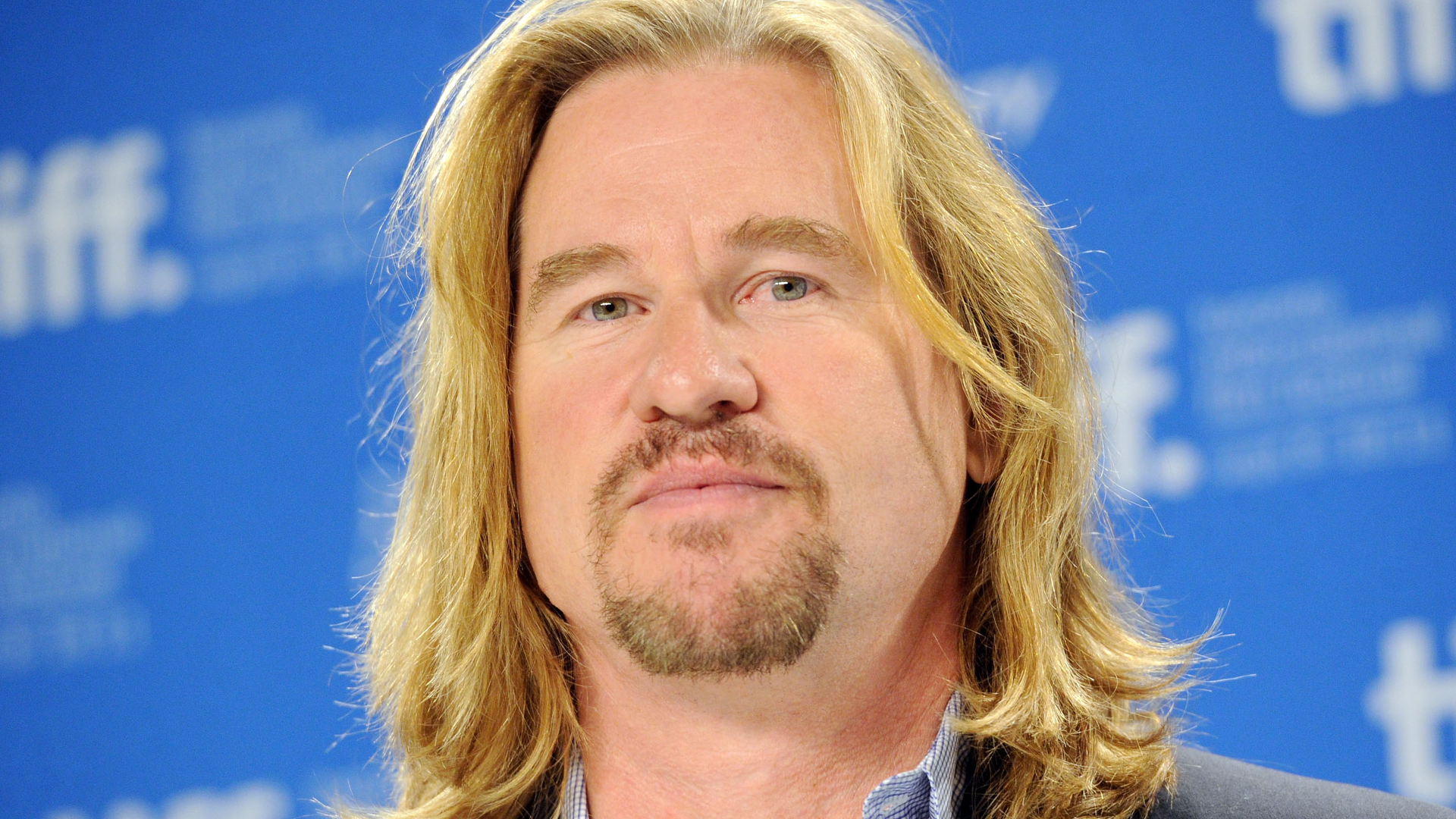

Val Kilmer’s Health Journey: From Iconic Hollywood Star to a Voice of Resilience

Unlocking Justice: How the Irc Sheriff Inmate Search Powers Real-Time Public Safety

Exploring The Life And Career Of Jessica Nicole Smith: From Rising Star To Industry Voice