Is the MLE Estimator Biased? The Truth Behind Maximum Likelihood’s Hidden Flaws

Is the MLE Estimator Biased? The Truth Behind Maximum Likelihood’s Hidden Flaws

The Maximum Likelihood Estimator (MLE) stands as one of the most powerful and widely adopted tools in statistical inference, celebrated for its consistency, asymptotic efficiency, and elegance in deriving optimal parameter estimates. Yet, beneath its sophisticated reputation lies a persistent question: Is the MLE truly unbiased, or does its consistency come at the cost of systematic error? For researchers and practitioners alike, understanding the bias dynamics of MLE is critical to reliable interpretation of data—a faint misjudgment that can ripple through model-based conclusions.

This article dives into the nuanced reality of MLE bias, dissecting its theoretical foundations, real-world implications, and the conditions under which bias emerges, all while clarifying what’s fact and what’s misconception.

The Theoretical Promise: When MLE Behaves Well

At its core, the MLE identifies parameter values that maximize the likelihood of observing the sample data. Under ideal regularity conditions—such as identifiability, finite moments, and continuity of the likelihood function—the estimator converges in probability to the true parameter value as sample size grows.This property, known as **consistency**, assures that larger datasets yield more accurate estimates. But consistency does not equate to unbiasedness. Bias, defined as the difference between the estimator’s expected value and the true parameter, may persist even as n approaches infinity depending on the model and data structure.

MLE is often assumed to be unbiased in simple, finite-sample settings—particularly with symmetric, well-behaved distributions like the normal model with known variance. Yet, this “unbiasedness” is an asymptotic illusion. As one statistician noted, “MLEs tend to be biased in finite samples but approach truth with precision—like a dart throw gaining sharper focus the more points are scored.” This metaphor captures the essence: while bias diminishes under large samples, it doesn’t vanish overnight.

Sources of Bias: When MLE Stumbles

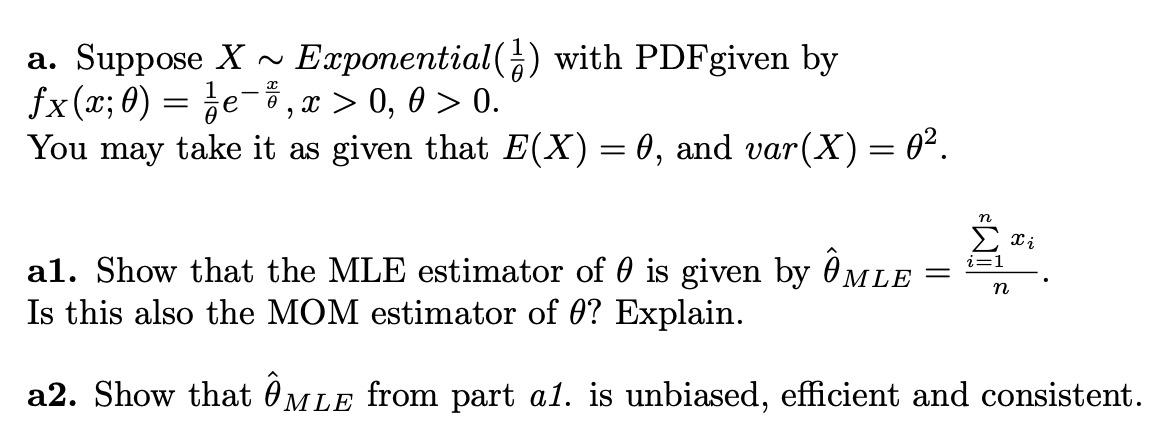

Bias in MLE arises not from flawed design but from structural mismatches between model assumptions and reality. Key sources include: - **Sample Size Limitations**: With small or moderate datasets, the likelihood surface can be skewed, causing MLEs to overshoot or undershoot the truth. For instance, in estimating exponential distribution parameters from sparse observations, MLE often exhibits downward bias.- **Model Misspecification**: When the assumed distribution deviates from the data-generating process—such as fitting a normal model to heavy-tailed data—the likelihood function misleads, dragging estimates away from reality. - **Non-regular Models**: When likelihood functions fail to satisfy standard regularity conditions (e.g., discontinuous likelihoods or non-differentiable parameter spaces), MLE bias becomes systematic and unpredictable. Each pathway reveals a vulnerability: MLE’s strength—its reliance on precise likelihood maximization—also exposes weaknesses when assumptions falter or data is insufficient.

Empirical Evidence: Real-World Implications of MLE Bias

In practice, MLE bias manifests across disciplines, from biology to machine learning. Consider a classic example: estimating the mean and variance of a normal sample with unknown parameters. The traditional MLE for variance divides by n, introducing bias; the unbiased estimator uses n–1 (Bessel’s correction), a correction that underscores inherent MLE limitations.Without it, risk traps increase—and inferences grow misleading. Another instructive case appears in logistic regression, where MLE estimates odds ratios. While asymptotically unbiased, finite-sample bias can distort risk estimates in predictive modeling, potentially undermining clinical or policy decisions.

In high-stakes fields like epidemiology or finance, such bias isn’t just statistical noise—it’s a silent driver of suboptimal outcomes. Even Bayesian perspectives, which contest classical frequentist bias definitions, acknowledge MLE’s finite-sample shortcomings. As noted in methodological literature, “MLE bias in finite settings is not a flaw but a feature—one that warrants correction, especially when precision outweighs theoretical elegance.”

Mitigating Bias: Strategies for More Reliable Estimates

Recognizing that MLE bias is not theoretical grenade but manageable hazard, researchers employ several tactics to enhance estimator accuracy: - **Bootstrap Resampling**: Repeated sampling from observed data simulates the likelihood’s behavior, enabling bias-corrected estimates without changing the model.- **Adjusted Estimators**: Modifications like the debiased MLE or generalized reliable inference correct finite-sample bias while preserving efficiency. - **Bayesian Integration**: Combining MLE with informative priors stabilizes small-sample estimates, reducing bias through regularization. - **Robust Standard Errors**: Accounting for model misfit through robust inference frameworks guards against overreliance on points estimates.

These strategies reflect a pragmatic shift: rather than reject MLE, practitioners adapt it—layering safeguards that transform a theoretically biased tool into a practically reliable instrument.

The Bias-Efficiency Trade-off: When Precision Demands Compromise

The debate over MLE bias ultimately hinges on a foundational statistical trade-off: bias often diminishes at the cost of efficiency, or worse, introduces variability that destabilizes inference. MLE, by design, prioritizes consistency and asymptotic optimality—properties that favor large samples but falter in practice’s noisy constraints.This tension is not flaw but feature: choosing between bias and efficiency depends on context. For exploratory studies or small datasets, accepting controlled bias may be preferable to ambiguous, inconsistent estimates. In contrast, confirmatory research demands low bias, justifying bias correction or alternative methods.

The MLE’s power lies not in absolute correctness but in its adaptability—guiding analysts to recognize thresholds where “good enough” aligns with real-world reliability.

The Path Forward: Bias as a Guide, Not a Barrier

Is the MLE estimator biased? Yes—especially in finite samples and misaligned models.But this truth need not be a limitation. By understanding bias as a predictable, quantifiable phenomenon, statisticians convert vulnerability into control. The dominant narrative—“MLE is biased, therefore untrustworthy”—is outdated.

Today’s data science embraces MLE’s asymptotic brilliance while applying nuanced corrections to deliver accurate, actionable insight. In the evolving landscape of statistical practice, bias in MLE is not a flaw to fear but a signal to refine—affirming that rigorous inference balances principle with pragmatism, theory with real-world application. The next time you apply MLE, remember: its imperfections reveal pathways to deeper understanding, turning uncertainty into informed confidence.

Related Post

Nick Nolte: The Unyielding Force Behind a Legacy Forged in Bold Roles and Relentless Craft

From the Shadows of the Silhouette: Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Son’s Journey From Obscurity to Resilience

Redmond O’Neill: Architect of Financial Clarity in a Storm of Complexity

Is Isolator Roblox Scary A Deep Dive