Is Brazil a Third World Country? Decoding Development, Inequality, and Global Status

Is Brazil a Third World Country? Decoding Development, Inequality, and Global Status

Brazil remains a nation defined by contrasts—vast natural wealth juxtaposed with deep social divides, rising global influence shadowed by persistent challenges. The question of whether Brazil qualifies as a “Third World” country reveals more than a historical label; it exposes complex layers of economic development, social inequality, and evolving global positioning. While outdated Cold War-era categorizations no longer reflect Brazil’s dynamic reality, the term lingers in public discourse, demanding a factual, nuanced examination grounded in current economic, social, and geopolitical data.

Historically, the “Third World” label emerged during the mid-20th century to describe countries that were neither aligned with the Western capitalist bloc nor the Eastern communist sphere—nations often struggling with underdevelopment, colonial legacies, and state-led modernization. Brazil never faced outright ideological conflict but has long grappled with structural issues rooted in unequal wealth distribution, rural-urban disparities, and uneven access to education and health services. Economically, Brazil ranks among the top 12 largest national economies by GDP (nominal, 2023), with significant agricultural, industrial, and service sectors.

Yet, this macroeconomic strength coexists with deeply entrenched poverty: according to Brazil’s National Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE), over 20% of the population lives below the poverty line, and extreme poverty affects nearly 5%. These figures underscore that Brazil’s development remains incomplete, echoing characteristics once attributed to Third World nations.

Skyrocketing Inequality: The Unseen Shadow of “Third World” Perceptions

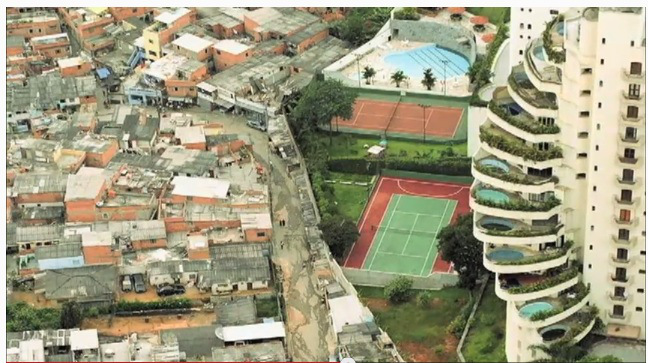

The perception of Brazil as a Third World country is strongly tied to its most visible and persistent challenge: inequality.The country ranks among the most unequal societies globally, with a Gini coefficient exceeding 0.53—well above the United Nations’ threshold for high inequality. “You see vast extremes in Brazil: gleaming skyscrapers and sprawling favelas side by side, international corporations beside subsistence farmers,” notes economist Candido Lima of the Brazilian Economic Policy Institute. This duality shapes both national identity and international narrative, attributing to Brazil a reputation for social fragmentation uncommon in upper-middle-income nations.

Genealogies of inequality trace back centuries: colonial extraction, the legacy of slavery (abolished in 1888, the last Western country to do so), and concentration of land and capital among elite families. Even post-1988 democratic reforms expanded access to education and healthcare, but structural barriers persist. Rural populations, especially Indigenous and Afro-Brazilian communities, face limited connectivity, lower life expectancy, and restricted economic mobility.

Urban centers, though dynamic, reflect spatial segregation—wealthy neighborhoods circle privileged zones while marginalized communities endure overcrowding and inadequate infrastructure. This inequality undermines inclusive growth, casting a long shadow over Brazil’s global image.

Economic Foundations: From Commodities to Consumption Power Economically, Brazil’s trajectory departs sharply from classic Third World dependency.

While history is marked by export-oriented agriculture—coffee, sugar, minerals—today,

Related Post

Is Brazil a Third World Country? Untangling the Myth Behind Development, Reality, and Progress

Is Brazil a Third World Country? Unveiling the Truth Behind the Labels

Laura Harrier: From Indie Exposure to Mainstream Impact in Movies and TV

Is Lara Trump Catholic? Decoding Her Faith, Background, and Public Identity