Is Acceleration a Vector or Scalar? Unlocking the Nature of Motion

Is Acceleration a Vector or Scalar? Unlocking the Nature of Motion

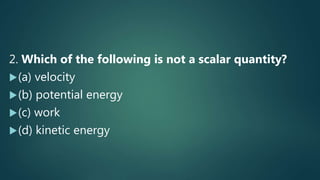

Acceleration is not merely a number—it is a fundamental concept in physics that demands precise classification: is it a vector or a scalar? The answer lies in the geometric and physical behavior of how acceleration describes motion. Far from a mere scalar magnitude, acceleration is inherently a vector quantity, encoding both the rate of change of velocity and direction.

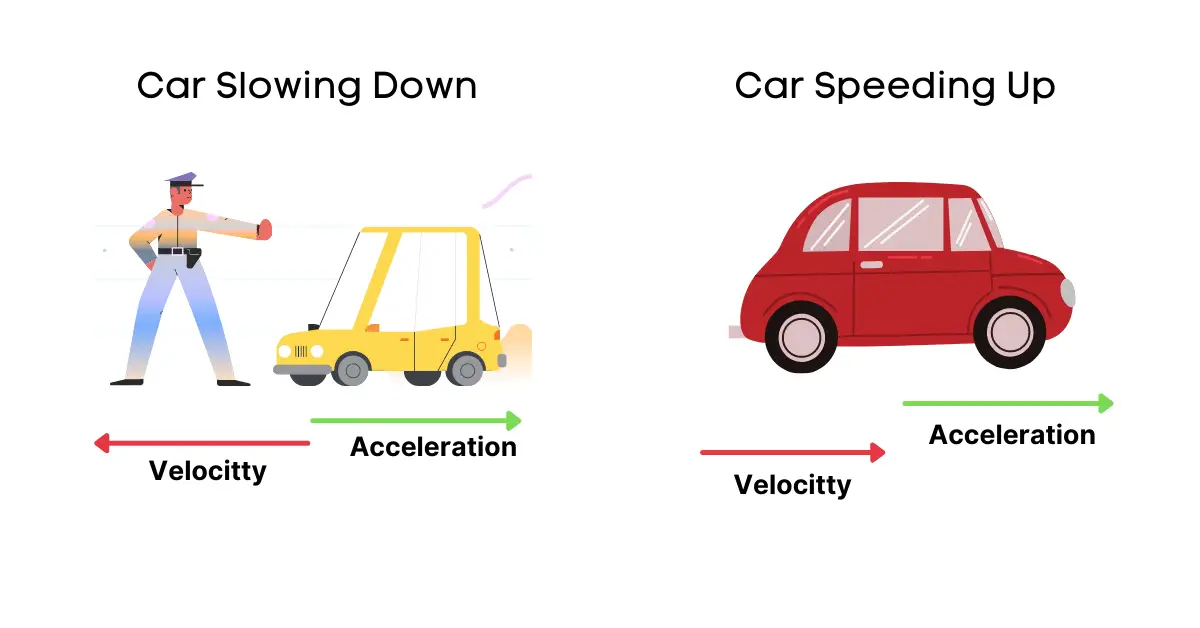

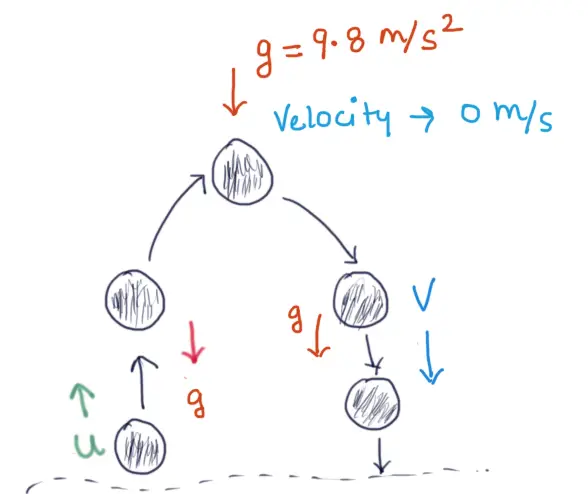

Understanding this distinction clarifies core principles in kinematics and dynamics, influencing everything from vehicle safety systems to celestial mechanics. Acceleration is defined as the derivative of velocity with respect to time, which immediately suggests its vector nature. Velocity itself is a vector: it possesses both magnitude (speed) and direction.

Since acceleration measures how velocity changes vectorially—shifting not only in speed but potentially in direction as well—it must represent a quantity with direction. A scalar, by definition, has magnitude only. “A vector points in space and has direction,” explains Dr.

Elena Torres, a professor of mechanical engineering at MIT. “Acceleration does exactly that—it changes the vector of velocity, which inherently requires directionality.”

While the scalar value of acceleration’s magnitude—say, 5 meters per second squared—answers “how fast speed changes,” it does not capture the full picture. Direction is critical in physics because motion trajectories depend on both how quickly an object speeds up or slows down, and along which axis.

For example, an object accelerating eastward at 10 m/s² differs physically from one accelerating northward at 10 m/s², even if magnitudes are equal. “Magnitude alone tells part of the story—unfortunately, velocity is directional, and acceleration reflects changes in that direction,” notes physicist James Holloway. “Omitting direction reduces acceleration to a scalar, losing essential information about motion dynamics.”

Mathematically, acceleration’s defintion as dv/dt involves a vector differentiation.

When velocity vector **v**(t) = [vₓ(t), vᵧ(t), v_z(t)], acceleration **a**(t) = [aₓ(t), aᵧ(t), a_z(t)] is the time derivative of each component. Each component evolves independently, yet their vectorial sum defines overall motion. This multi-component vector nature ensures acceleration propagates directional changes coherently.

“In vector form, acceleration isn’t a single number but a set of three rates—each explaining acceleration along x, y, z axes,” explains Dr. Hiro Nakamura, author of advanced mechanics textbooks. “That structure is incompatible with scalars, which have only magnitude.”

Consider a car undergoing circular motion: even at constant speed, the car changes direction continuously.

Its velocity vector rotates over time, requiring a centripetal acceleration directed toward the center. This acceleration is clearly vectorial—its direction continuously shifts, guiding real-world applications like tire traction analysis and collision avoidance systems. “A scalar acceleration would falsely imply uniform direction change, missing the curvature essential to real motion,” clarifies Dr.

Nakamura. “Vectors capture the full kinematic reality.”

In kinematics equations, acceleration appears as **a** = **a**ₓ**i** + **a**ᵧ**j** + **a**_z**k**, reflecting precise directional influence on motion. When analyzing projectile paths or satellite orbits, vector acceleration enables accurate trajectory prediction.

“Introducing a scalarmodel would collapse these nuances, making equations incomplete or misleading,” warns Holloway. “Acceleration as a vector is indispensable for capturing directional dynamics.”

From classroom demonstrations to cutting-edge aerospace engineering, the vector nature of acceleration shapes how we teach and apply physics. In vehicle safety systems, angular acceleration data guides crumple zones and airbag timing.

In robotics, vector acceleration controls precise joint movements. “Without treating acceleration as a vector, automation technologies rely on incomplete models—compromising efficiency and safety,” argues Torres. “It’s not just theory; it’s the foundation of functional design.”

In technology, gear control algorithms depend on accurate vector acceleration data to modulate power efficiently.

Accelerometers and inertial measurement units capture vector acceleration, feeding real-time feedback to systems from smartphones to spacecraft. “Vector data is how machines ‘feel’ motion,” says Nakamura. “Scalars alone cannot provide the spatial insight needed.”

Yet, slip into scalar thinking at one’s peril.

In school physics, equations mistakenly equate acceleration with mere value—ignoring direction—leading to errors in problem-solving. “Students often treat acceleration as a number instead of understanding its vector identity,” observes Professor Torres. “Correct comprehension is vital; acceleration’s vector nature underpins nearly every motion-related science.”

The debate may hinge on whether acceleration’s magnitude is emphasized, but ignoring its vector sinews distorts fundamental understanding.

Acceleration is not scalable—it demands vector treatment to accurately model direction and change. Whether analyzing car crashes, planetary motion, or industrial robots, recognizing acceleration’s vector identity ensures precision and innovation. It is, without question, a vector—not a scalar.

#AccelerationIsVector—not merely accurate, but essential.

Related Post

Astro A50 Gen 4: How to Update Firmware with Effortless Precision

Emirates: The Sultanate of Ambition, Innovation, and Cultural Pride in the Middle East

Vega Thompson’s Exclusive Universe on Vega Thompson Onlyfans: A Deep Dive into Her Digital Empire

Jennifer Peña’s Net Worth: From Rising Star to Hollywood Power Player