How Biotic and Abiotic Conditions Shape Life on Earth: The Silent Dance of Survival

How Biotic and Abiotic Conditions Shape Life on Earth: The Silent Dance of Survival

In every ecosystem, from sun-drenched deserts to deep ocean trenches, life thrives through an intricate balance of living (biotic) and non-living (abiotic) forces. Biotic interactions—such as competition, predation, and symbiosis—occur against a backdrop of abiotic conditions like temperature, water, soil chemistry, and light availability, collectively determining where and how organisms survive. Understanding how these forces interact reveals a dynamic, often fragile equilibrium that underpins biodiversity and ecosystem resilience.

Carbon markets, renewable energy growth, and water governance — many human systems mirror nature’s delicate interdependencies. Just as roots bind soil and microbes drive nutrient cycles, biotic and abiotic factors stabilize ecosystems, supporting complex, self-sustaining webs. When one condition shifts—whether from climate change, deforestation, or pollution—the entire system responds, sometimes with resilience, but often with cascading disruption.

Biotic conditions encompass all living components influencing an organism’s environment—plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, and viruses—each contributing to nutrient cycling, pollination, and habitat structuring. Abiotic factors, in turn, include temperature ranges, pH levels, mineral composition, moisture availability, solar radiation, and atmospheric gases. These physical and chemical elements define the limits of life, shaping the geographic distribution and evolutionary trajectories of species.

“Soil pH, water availability, and temperature are not just background noise—they are active architects of ecological order,” notes Dr. Elena Torres, a molecular ecologist at the Global Institute for Ecosystem Dynamics. “They determine which microbes thrive, which plants take root, and ultimately, which animals stay or move.” Consider coral reef ecosystems: vibrant and biologically rich, they depend on a narrow window of abiotic conditions.

Corals host symbiotic algae (a key biotic element) that rely on warm, clear, sunlit waters with stable salinity and minimal sediment. When ocean temperatures rise or pollution alters water chemistry, these relationships shear apart: bleaching events decimate reefs, with cascading effects on fish populations and coastal protection. A single shift in abiotic parameters can unravel networks forged over millennia through biotic cooperation.

Similarly, in arid deserts, though life seems sparse, biotic interactions intensify survival strategies. Microbial crusts stabilize soil, retain moisture, and foster pioneer plants—each adaptation shaped by extreme heat and aridity. Biotic feedbacks modify abiotic conditions, increasing organic content and reducing erosion over time.

As ecologist James Holloway explains, “Desert soils enriched by biotic activity become microhabitats that buffer abiotic extremes, enabling longer-term colonization and community development.” These systems prove that life doesn’t passively endure—it actively modifies its world. The balance between biotic and abiotic forces operates on multiple scales. Locally, a single tree alters microclimate, soil nutrients, and light penetration, reshaping which organisms flourish nearby.

Regionally, climate patterns—driven by ocean currents and atmospheric conditions—dictate biome distribution. Globally, shifting abiotic baselines, such as rising CO₂ levels or glacial melt, disrupt long-established biotic relationships, driving migrations, extinctions, and novel ecosystem configurations. Few examples illustrate this more vividly than alpine ecosystems.

These high-altitude zones feature short growing seasons and harsh, icy conditions—abiotic constraints that limit growth and species diversity. Yet here, alpine plants and pollinators co-evolved precise timing and adaptations: flowers bloom rapidly in brief warm spells, bees adjust foraging rhythms, and soil communities stabilize thin, nutrient-poor substrates. “The biotic community is finely tuned to the abiotic orchestra—the wind, snowmelt, and solar radiation dictating rhythm,” clarifies Dr.

Mira Chen, a biogeographer researching climate impacts. “Any alteration throws the timing into disarray, threatening entire food webs.” In urban environments, the interplay shifts but remains critical. Heat islands rise due to concrete and asphalt—abiotic changes amplifying temperature extremes—altering native species distributions and favoring invasive, heat-tolerant organisms.

Water runoff patterns shift as land is paved, modifying hydrology and stressing native flora. Yet green roofs, urban parks, and rain gardens demonstrate how intentional biotic interventions—introdu

Related Post

Jeff Tanchak’s Wife: Behind the Public Figure, A Quiet Life of Grace and Resilience

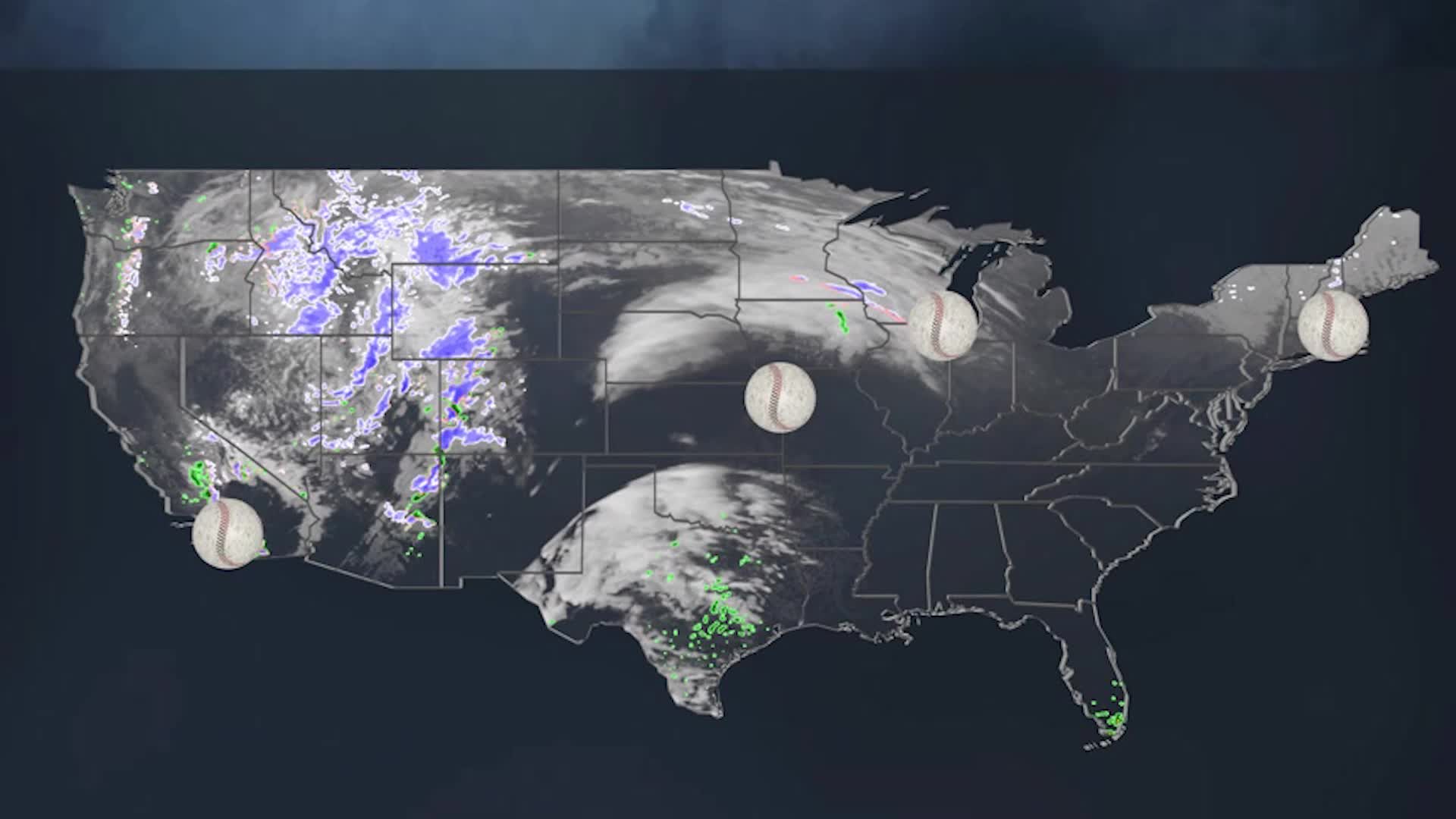

The Pulse of the Diamond: Mlb Weather Forecast Today and How Game Day Conditions Shape Gallery Fever

How Life Multiplies: The Precision of Binary Fission and Mitosis in Cellular Replication

Clickpoint CNA: The Backbone of Complex Claims Navigation in Modern Insurance