Do Prokaryotes Have a Nucleus? The Hidden Truth Behind the Absence of a True Nucleus

Do Prokaryotes Have a Nucleus? The Hidden Truth Behind the Absence of a True Nucleus

Far longer debated than the nucleus itself, the question of whether prokaryotes possess a nucleus reveals a fundamental divergence in cellular complexity that shapes biology’s earliest evolutionary branch. While eukaryotes enclose their genetic material within a membrane-bound nucleus, prokaryotes—comprising bacteria and archaea—lack this defined compartment, relying instead on a simpler, open architecture. This structural distinction is not merely anatomical; it reflects a deeper divergence in cellular organization, gene regulation, and evolutionary adaptation.

Understanding why prokaryotes lack a nucleus unlocks critical insights into life’s foundational design and the origins of cellular specialization.

Unmasking the Prokaryotic Cell: No Nucleus, But Not Without Purpose

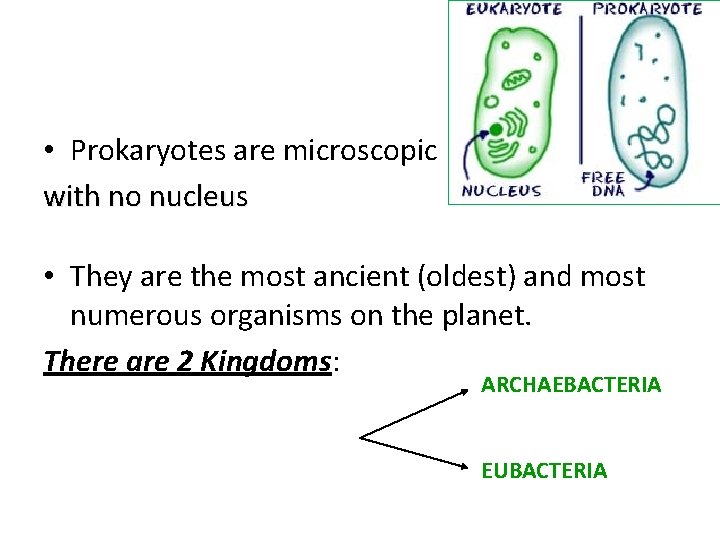

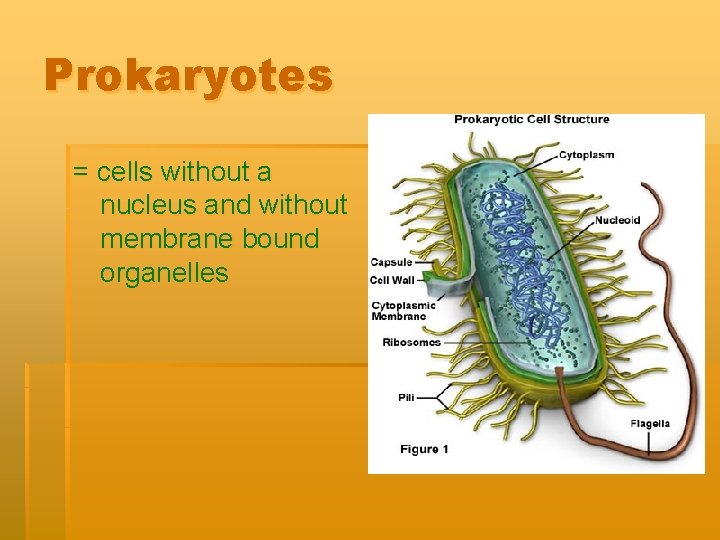

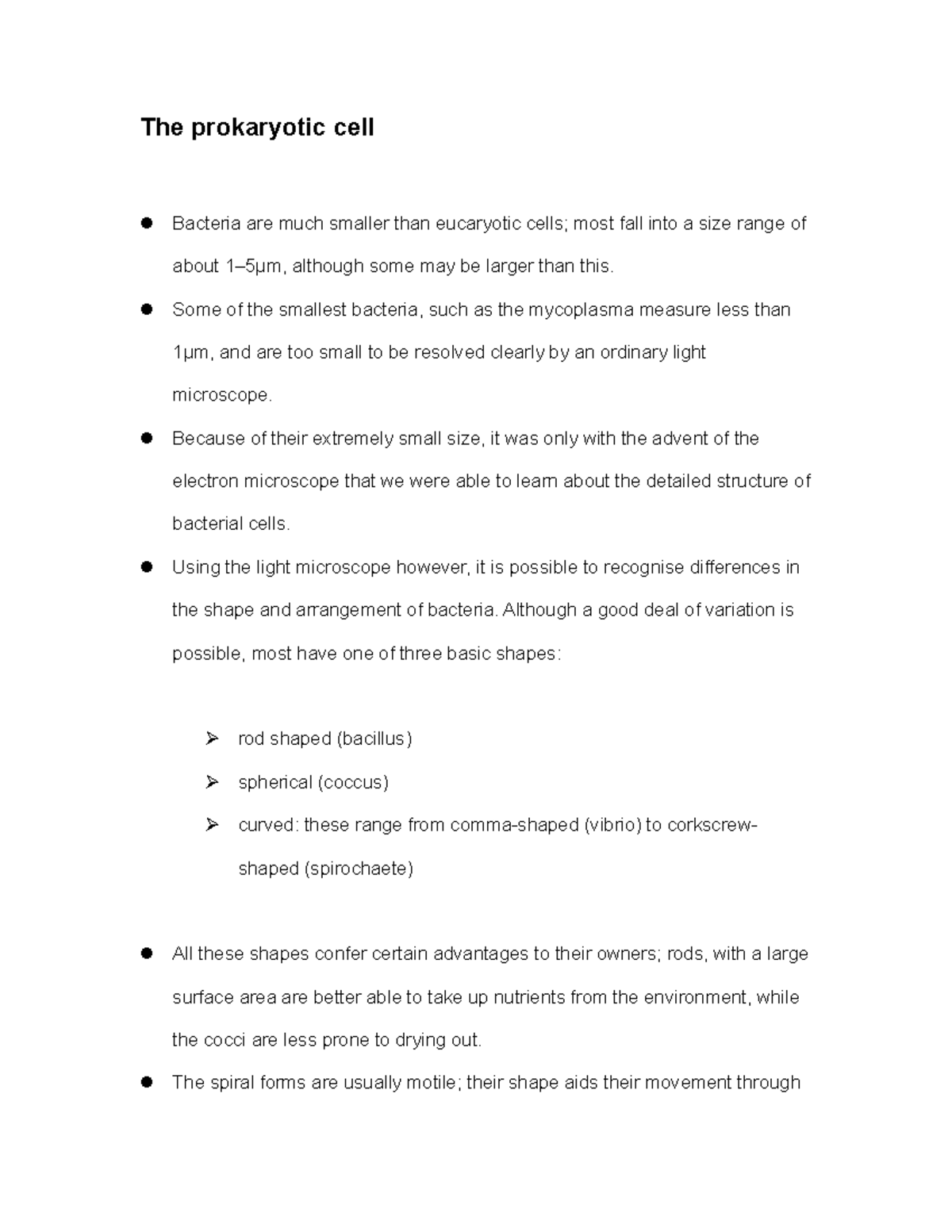

Prokaryotic cells, among the oldest and most abundant life forms on Earth, are defined by their minimalist architecture. A defining feature is the absence of a nucleus—a membrane-bound organelle that separates chromosomes from the cytoplasm in eukaryotes. Inside bacteria and archaea, the genetic blueprint resides not inside a structured envelope but free-floating in the cytoplasm, bound only by a thin nuclear membrane that is structurally and functionally distinct.

Unlike eukaryotic nuclei, which regulate gene expression, protect DNA from environmental threats, and compartmentalize cellular processes, the prokaryotic nucleoid region is unenclosed and dynamically integrated into the cell’s metabolic flow.

What makes this remote, uncharted genetic region particularly remarkable is its efficiency. Despite lacking a nuclear barrier, prokaryotes maintain precise control over DNA replication, transcription, and repair through protein complexes, localized transcription factors, and dense chromatin-like organization. As researcher David Drew notes, “Prokaryotes achieve functional compartmentalization not through membranes but through spatial regulation and molecular choreography—proof that complexity exists in forms beyond membrane boundaries.”

The nucleoid, as this region is called, is not a blank slate.

It contains single, typically circular chromosomes organized around a nucleoid-associated protein (NAP) complex that organizes and protects DNA. This 3D organization allows temporal control of gene expression and rapid response to environmental changes—critical advantages in fluctuating habitats. In contrast, eukaryotic nuclei feature multiple chromosomes enclosed by two lipid bilayer membranes, enabling intricate nuclear pores, specialized RNA processing, and segregation of transcription from translation—a hallmark of eukaryotic efficiency.

The prokaryotic system, while fundamentally simpler, is exquisitely adapted to its ecological niche, where speed and simplicity often outweigh structural isolation.

The evolutionary rationale for the absence of a nucleus is rooted in cellular economy. Prokaryotes thrive in diverse environments—from extreme heat to oxygen-starved soils—and their streamlined genome architecture supports rapid replication and adaptability. A membrane-less nucleus eliminates the energy cost of envelope maintenance and nuclear transport, allowing these cells to divide within minutes under optimal conditions.

This modular efficiency challenges assumptions that nuclear complexity inherently signals evolutionary advancement. As biologist Lynn Margulis observed, “The prokaryotic ‘naked’ genome is not a primitive error but a sophisticated solution optimized for survival without compartmental walls.”

Structural and Functional Implications: How Prokaryotes Compensate for Lacking a Nucleus

While prokaryotes lack a nucleus, they deploy alternative mechanisms to ensure genomic integrity and functional regulation. The nucleoid region is enriched with proteins that stabilize DNA, facilitate replication initiation, and mediate repair.

For instance, DNA gyrase, a topoisomerase, manages torsional stress during replication, while Ku proteins protect DNA ends—functions analogous to those performed by nuclear repair enzymes. These molecular scaffolds, though diffusely organized, create functional zones that simulate compartmentalization.

Gene regulation in prokaryotes diverges significantly from eukaryotes. Transcription occurs freely in the cytoplasm, with RNA polymerase binding directly to promoter sequences often accelerated by sigma factors—alternate protein subunits that direct promoter recognition.

Translation, meanwhile, begins mid-replication, enabling immediate protein synthesis from newly copied DNA—a tight coupling unfeasible in eukaryotes, where transcription and translation are spatially and temporally separated within the nucleus.

This dynamic interface allows rapid adaptation. In rapidly changing environments, prokaryotes can swiftly reprogram gene expression without the lag of nuclear transport. A single gene’s transcription, coupled with immediate translation, enables response times measured in seconds rather than minutes—a critical edge in microbial warfare, nutrient scavenging, and symbiotic interactions.

Another pivotal difference is chromosome organization.

While eukaryotic DNA is linear and tightly packaged into histones, prokaryotic genomes are typically circular and loosely associated with nucleoid-associated proteins, forming nanoparticle-like clusters. These clusters cluster essential genes near the cell center, facilitating coordinated expression—a spatial organization that enhances functional coherence despite structural simplicity. This architectural economy does not diminish genomic complexity.

Prokaryotes possess regulatory RNA molecules, CRISPR systems for adaptive immunity, and extensive horizontal gene transfer mechanisms—features that rival eukaryote gene exchange in sophistication. As noted by molecular biologist Carl Woese, “The absence of a nucleus did not silence evolutionary potential; it redirected it into novel computational and regulatory domains.”

The Evolutionary Significance: From Nucleus-Less Cells to Complex Life

The prokaryotic genome without a nucleus stands as a testament to evolutionary innovation through simplicity. The nucleus, a defining feature of eukaryotes, likely emerged during eukaryogenesis—around 1.6 to 2 billion years ago—through a fusion event involving archaeal hosts and bacterial symbionts.

This endosymbiotic origin transformed cellular life by enabling compartmentalization, a step linked to the rise of multicellularity and specialized tissues. Yet prokaryotes, having thrived for over 3.5 billion years without it, demonstrate that life can flourish through alternative organizational paradigms.

The prokaryotic nucleoid, far from being a deficiency, reflects an alternative trajectory—one where genomic control is achieved through molecular precision rather than physical separation. This divergence reshapes our understanding of biological complexity: sophistication is not measured solely by membrane-bound compartments but by the efficiency and adaptability of molecular systems enduring over geological time.

From endospores enduring sterilization to pathogens spreading through rapid gene exchange, prokaryotes exemplify nature’s versatility.

Their nucleus-free design challenges simplistic narratives of evolution, emphasizing that the greatest adaptations are not always the most complex—but the most well-suited.

Ultimately, the absence of a nucleus in prokaryotes

Related Post

Indulge In The Sweetness Of Technology: The Chocolate Phone

Unbl Games Redefine Immersive Play: Where Storytelling Meets Revolutionary Mechanics

Open Source News Is Reshaping Global Media: How Free, Collaborative Data Is Revolutionizing Journalism

Surviving the Unexpected: Emergency Landing in Roblox Mobile