Did China’s Debt Fuel Bankrupt Cycles in Developing Nations?

Did China’s Debt Fuel Bankrupt Cycles in Developing Nations?

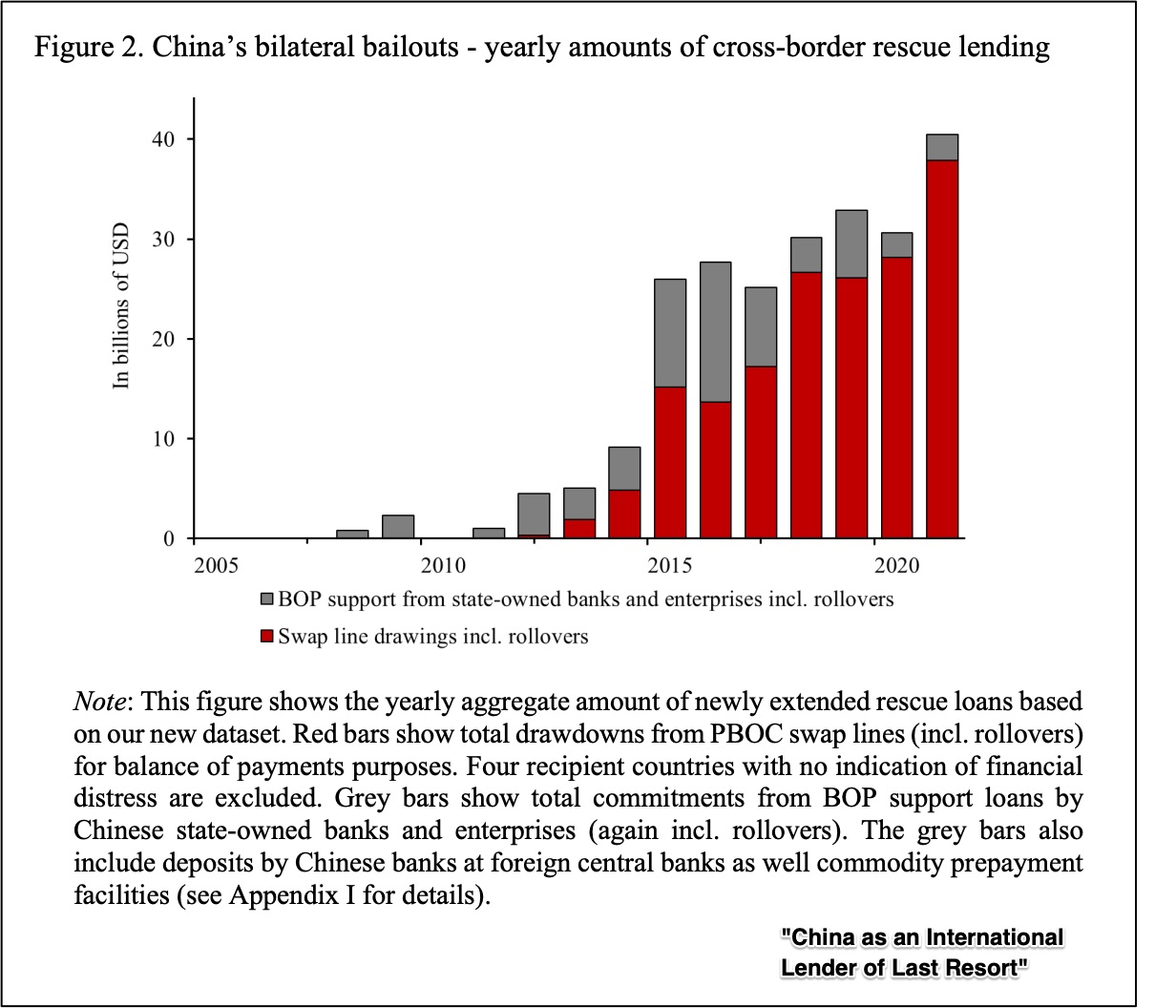

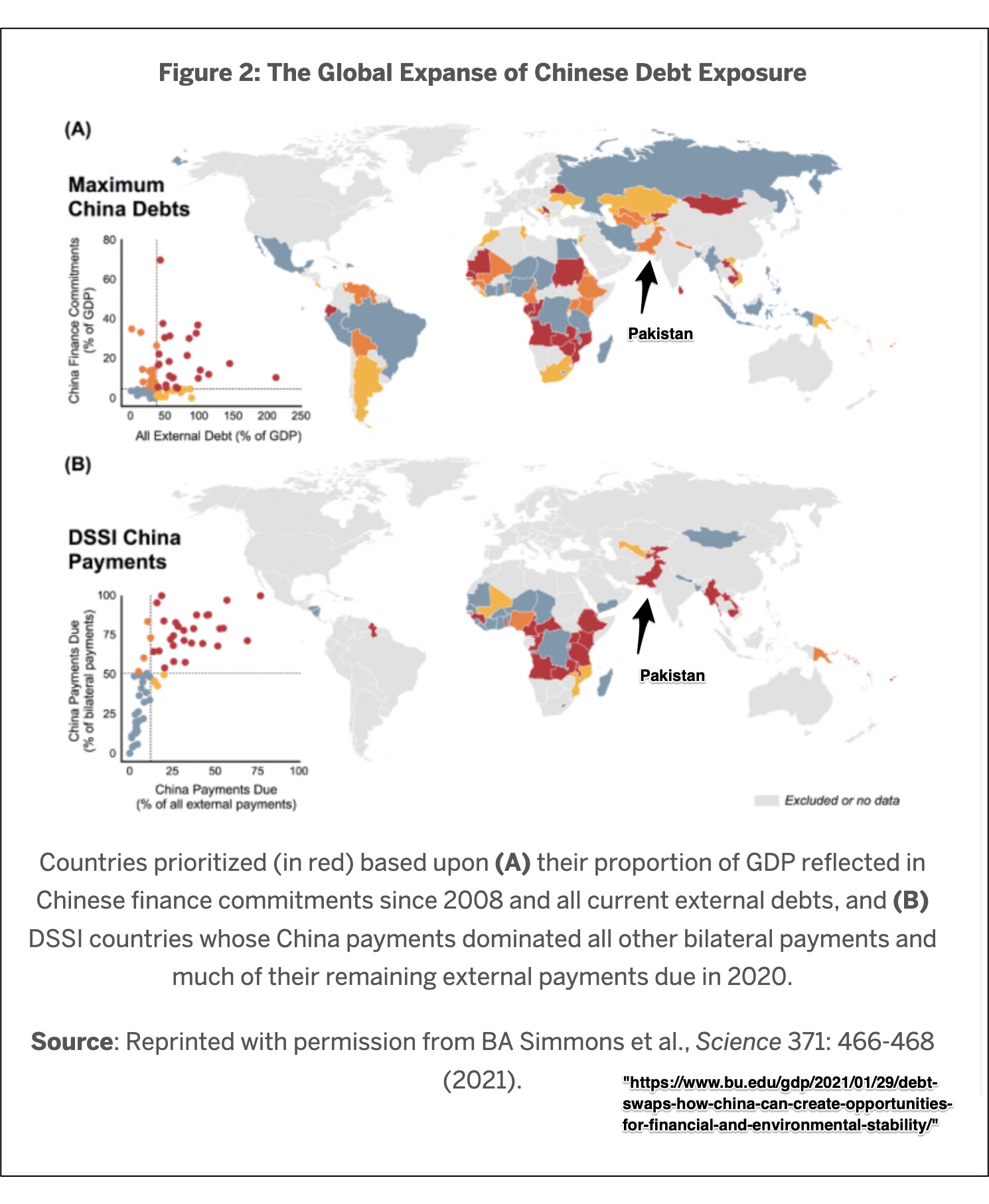

China’s rapid expansion of lending through infrastructure financing and sovereign loans has positioned it as a major global creditor, particularly in developing countries. While Beijing frames its financing as development partnership, critics raise urgent questions: is China’s debt practices contributing to sovereign bankruptcies? Evidence suggests a troubling pattern where excessive borrowing, tied to opaque contracts and rapidly shifting market conditions, has overwhelmed national balance sheets, triggering debt distress in several nations.

The narrative reveals not just financial risk, but shifting power dynamics in global lending, with long-term implications for economic sovereignty and development.

China’s role as a debt provider has surged over the past two decades, driven by strategic goals to expand influence across Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia. State-backed institutions like the Export-Import Bank of China and policy banks such as the China Development Bank channel billions into roads, railways, and energy projects. Unlike traditional Western lenders constrained by international standards, Chinese lending often lacks rigorous conditionality and transparency, enabling rapid disbursement but reducing accountability.

As economist Dueña Perera notes, “China’s model offers speed but weakens debt sustainability frameworks—when repayment pressure mounts, default risks rise.”

Patterns of Loan-Bound Debt and Sovereign Defaults

Several developing nations have experienced debt distress linked to China’s financing. Among the most cited cases is Sri Lanka, where infrastructure projects funded in part by Chinese loans contributed to a 2022 constitutional crisis after debt servicing drained foreign reserves. Similarly, Djibouti’s overreliance on Chinese financing to fund port and railway expansions left it with external debt exceeding 77% of GDP, triggering defaults in 2020 and 2023.

Mozambique also exemplifies the risk: a $2 billion hidden loan scandal in 2016 revealed large-scale borrowing from Chinese banks without parliamentary oversight, later deemed unsustainable and leading to default proceedings.

Key indicators of vulnerable economies include rising debt-to-export ratios, heavy dependence on a few export commodities, and rising imported debt servicing costs. In Zambia, under Chinese-backed mining infrastructure, debt service reached 40% of exports by 2023, straining fiscal space. “Chinese loans are often opaque—we didn’t see full terms upfront,” said a Zambian finance official.

“When interest rates climbed and commodity prices faltered, repayments became impossible.” These trends align with World Bank data showing that nations with China as their largest bilateral creditor increased external debt from 27% of GDP in 2010 to 58% in 2022.

Why China’s Debt Practices Differ—and Raise Concern

Chinese lending differs structurally from institutions like the IMF or World Bank. While recipient countries must meet strict conditionalities—often tied to governance reforms—Chinese loans typically require buy-back from Chinese firms and banks, creating an uneven dependency. “Beijing trades loans for resources and labor, which advances economic development but locks countries into long-term commitments,” explained a senior analyst at the Asiam institution Center for Strategic and International Studies.

This model avoids public oversight but risks locking debtor nations into asset-stripping agreements or strategic concessions.

Moreover, repayment schedules are often aligned with project completion rather than economic cycles, exacerbating stress during downturns. Scholars warn that without multilateral debt restructuring frameworks led by China, many nations remain trapped in cycles of borrowing and default. “When countries default, China’s response is inconsistent—sometimes renegotiations occur, but at delay,” noted a debt sustainability expert.

“The absence of a formal collective framework leaves creditors and debtors exposed to prolonged crises.”

The Role of Opaqueness and Gateway Agreements

Transparency—or the lack thereof—amplifies systemic risks. Many Chinese loans stem from bilateral “hard contracts” not subject to democratic scrutiny, enabling opaque deals closed between state agencies. Swiss bank analyst Thomas Lehner observes: “Without public audit trails, vulnerability assessment fails.

A project’s true economic viability, cost overruns, and contingent liabilities remain hidden.” These gateways often involve state-owned enterprises, making defaults faster and more difficult to reverse. In many cases, political pressures discourage early restructuring, fearing reputational damage and financial contagion.

For recipient governments, access to Chinese capital offers urgent development funds, but long-term debt sustainability is compromised when oversight is minimal and exit clauses are absent. Experts argue that strengthening domestic debt management institutions—enabling independent debt assessments and public reporting—is essential to mitigate systemic risks.

Global Implications and Shifting Geopolitics

China’s growing debt footprint has reshaped global financial architecture, challenging Western-led lending norms.

As nations default or restructure, Beijing’s influence grows—both financially and diplomatically. This shift complicates international efforts to stabilize debt crisis-hit economies, particularly where coordination between China, multilateral banks, and Paris Club creditors remains fragmented. Maintaining global financial stability increasingly depends on Japan, India, and European counterparts integrating China into cohesive debt relief mechanisms.

The broader lesson: while Chinese investment accelerates infrastructure development, its lending model—characterized by opacity, speed, and strategic entrenchment—heightens the risk of sovereign bankruptcy when macroeconomic shocks strike.

Without reform toward transparency and sustainability, debt-driven growth risks undermining economic resilience far beyond individual nations, fueling instability across emerging markets and altering power dynamics on a global scale.

As China continues to expand its role as a creditor, the debate intensifies over whether its financing model fosters equitable development or entrenches a new cycle of debt dependency. For policymakers and citizens alike, the urgency of transparent, accountable lending frameworks has never been greater—balancing development ambition with fiscal prudence to prevent borrowing from becoming a pathway to ruin.

Related Post

Beanpole Meaning: Unraveling the Crisis of Length Without Purpose

Navigating UK Law Professionals: Meet Jonathan Scott Taylor, Your Go-To Legal Advisor

Dyanna Lauren: From Rising Star to Resilient Icon in Film and Beyond

Jackson Hole Rodeo Jackson Wy: The Ultimate Fusion of Tradition and Thrill